Thee High Ate Us

Signing off for now with much Gratitude, Thoughts on Substack, Some (A)Political Ramblings, and an Analysis of Abel Ferrara and Art's Ever-Dangerous Game

“I believe one writes because one has to create a world in which one can live. I could not live in any of the worlds offered to me — the world of my parents, the world of war, the world of politics. I had to create a world of my own, like a climate, a country, an atmosphere in which I could breathe, reign, and recreate myself when destroyed by living. That, I believe, is the reason for every work of art.” – Anaïs Nin

A year ago today on July 18 2023, I launched this here little Substack blogthing, which has now culminated here in my 22nd post. A full year of publishing with an almost-average of two posts per month and a nice round number of 22 seems as good a place as any to stop, or at least take a break in order to regroup and rethink what I would like this project to become should I continue with it. For now, I look forward to getting back into a number of other projects before I abandon them altogether, including travel journals and films on Greenland, New York, Los Angeles, Tulsa, and Wales, not to mention the collection of interrelated stories I have been working on since 2019. It’s also high time for some new far-flung adventures, new sights and sounds. Time to unplug and recharge again. And who knows, perhaps I may finally complete the editing on the documentary about my uncle which I started a few centuries ago. Or even better yet, perhaps I will figure out how to best serve the world with the time and limited energy I have left.

I continue to ask myself what it is that compels me to write and to share my work with others. If the impetus was the pursuit of fame and fortune I would have quit many years ago. I believe that it’s something far less narcissistic and materialistic than that, at least I hope so. I certainly don’t regard myself as particularly talented or special. However, I do long to express myself and I long for connection with my fellow man. I want to be helpful and serve, perhaps even inspire. I do what I can with the very meager gifts I have been blessed with and try to stay sane in the process. So I write.

A few months back, my friend Julie J. gave me a copy of Rick Rubin’s book The Creative Act: A Way of Being. My feelings about Rubin are pretty ambivalent to say the least and tend toward the negative, and I have written a little about them here. But as I read the book with some trepidation, I found myself pleasantly surprised to find that amid Rubin’s stoned hippy guru posturings there were some real nuggets of wisdom and keen insights into what drives one to create even with the knowledge that all our works, like ourselves, are but food for the worms. To wit:

“Expressing oneself in the world and creativity are the same. It may not be possible to know who you are without somehow expressing it.”

“Sharing art is is the price of making it. Exposing your vulnerability is the fee. Out of this experience comes regeneration, finding freshness within yourself for the next project. And all the ones to follow.”

There, you have it; apparently I could not have said it better myself so thanks Rick, now get back to your bong hits and pizza.

And so, on a dare from my father as it were, I decided a year ago to share some of my writings both old and new here, but with a number of misgivings which I’ll try and address a bit. Substack proclaims itself to be some sort of mechanized savior of online human literature: Real human being writing and not tweets and trolls, providing a haven for long-form free thinking and free-speechifying philosophers, historians, journalists and the like now that “Print is Dead.” But it is also rather glaringly a part of the same problem it claims to be at war with. Writers are encouraged to get the word out about their columns through Facebook, Instagram, Twitter X, Linked In, etc. Ultimately Substack wants you plugged into the Machine like every other malignant and malevolent algorithmic force on the internet.

Before I began publishing on Substack, I rarely had anything to do with social media channels. Since starting this column I find myself wasting far too much time trying to, I guess, promote myself through channels I find distasteful, despicable and for the most part downright destructive. There is an unresolved dichotomy here between Substack’s goal of bringing and/or returning traditional literature and discourse to the internet and the soundbite social media tools which are its antithesis and which it encourages the use of in order to do so. A divided house that cannot stand, so to speak. If people want to engage in sustained reading, which they largely do not these days, they won’t be clicking on hyperlinks or checking email to do so.

The Substack format/platform is suspicious to me in countless other ways. For example, I for one read physical bound books almost exclusively. While I enjoy writing on a computer, I have a strong aversion to reading things on any electronic device. And so I would not read many of my own lengthy posts had I not written and extensively edited them myself, even though the subject matter is obviously to my liking. So despite Substack’s elitist claims of literary integrity, I believe the format is simply incompatible with the type of writing I am interested in presenting and the audience for it. Perhaps collecting some of my essays and self-publishing them in book form might be a better fit.

A related example: I have a good friend who posted his new novel in installments on Substack. While I like my friend’s writing very much, I simply could not keep up with reading any sort of sustained writing project on a computer. It made me physically ill to try and do so. And so, why should I expect anyone to keep up with my often very lengthy pieces?

On that note, I often hear from friends that I write so much that it is impossible to read it all and stay current with my posts. Some of these naysayers haven’t read a book in years, but point taken. If it’s on a computer then it apparently needs to be the length of a Facebook post or a tweet. Long-form writing is seemingly incompatible with electronic devices unless one manages to make peace with an e-reader device. Marshall McLuhan was right, ultimately the Medium is the Message and the message, or lack thereof, must be slave to the medium.

These thoughts have played a large part in my decision to take a break and attempt to figure out the best and most appropriate use for this forum, if any. To find a purpose for it. I have repeatedly stated that one of my intentions for Thee Vangarde has always been to provide a platform for the writing of others. While I have yet to be taken up on this offer, I continue to stand by it so hit me up if you’re interested in a guest spot here during my Substack sabbatical. I’ll be honored to post it for you and send out an email blast.

I firmly believe in the healing power of writing and I also believe that writing is a skill or a craft or a vocation rather than anything to do with innate natural talent. With practice, any literate person can put their thoughts in order and craft an effective essay. Certainly one’s formal and informal education and life experience plays a key role in becoming a worthy writer, but writers ultimately are made not born, with the exception of James Joyce of course. Having literary prowess is not some natural God given gift like a melodious voice, musical ability, a talent for drawing or painting, or physical beauty. It is an expression that must be cultivated out of sheer need for self-expression. If you feel you have something to say or share, you will feel much better when you do so. Just make the time and do it, even if only for yourself. Someone will bother to read it or just consider it therapy.

My hope for all the essays I have posted here has been to start a dialogue quite different and apart from what the regular channels of Facebook, Instagram, etc. seem to offer. I seek to exist in some lofty realm of art and ideas and always have. I have long believed that the culture of The Machine, of social media, of 24-hour “News,” of AI, has been detrimental to the very soul of mankind, not to mention our collective sanity and human connectedness. These are dangerous times for sure, but the most diabolical elements we face may have little to do with the environment or politics, at least not in the way such terms are often applied. One of my favorite youngish writers Paul Kingsnorth recently converted to Eastern Orthodox Christianity and has some remarkable if apocalyptic thoughts on this current Age of the Machine. Paul puts things much more eloquently than I ever could so give him a read here sometime. And thanks for spending time here with me over the last year; it means a lot.

“To be silent the whole day long, see no newspaper, hear no radio, listen to no gossip, be thoroughly and completely lazy, thoroughly and completely indifferent to the fate of the world is the finest medicine a man can give himself.” ~Henry Miller

From the beginning, I vowed to stay away from Politics on this platform because a) that seems to be all anyone can talk about anymore, and b) such talk is mostly dull-witted and ill-informed, c) it’s generally pointless and boring to me, and d) I find the prevailing tone of contemporary political discourse extremely disturbing and depressing. But recent events have prompted me to come out of the closet a little bit here in this final-for-now post. I hope you won't begrudge me for it.

A central problem in this country as I see it is the senseless devotion to the organized crime syndicates known as the Democratic and Republican parties who consistently demonstrate no real love or concern for, or meaningful connection with, those they seek to govern. If you are fully committed to Team Biden or Team Trump, nothing I can say will convince you otherwise. If however you are wavering a bit or find both options to be a fool’s errand and want real change in this country, please consider a third-party or independent candidate whose beliefs more closely align with your own. And yes, you’re right, such a candidate, an RFK Jr. for example, could never possibly get elected. True that, so long as we all keep thinking that way and continue to vote the establishment card. If we are truly at the crisis point both parties insist we are, what better time to vote with your heart for much needed change?

While I prefer the term apolitical in describing myself, a close and respected friend of mine recently wrote me off as hopelessly “politically disengaged" because of my refusal to align myself with one party or the other. Whatever, I feel that road leads to madness. To quote William Burroughs, “Fuck ‘em all; Squares on both sides.” I remain a dreamer, an idealist not an ideologue. An Anarchist at heart perhaps.

“The individual has always had to struggle to keep from being overwhelmed by the tribe. To be your own man is hard business. If you try it, you will be lonely often, and sometimes frightened. But no price is too high to pay for the privilege ~ Rudyard Kipling

Full disclosure: In the past two presidential elections, I’ve voted for both Donald Trump and Joe Biden. I had neither respect nor admiration nor belief in either beast and still don’t; it was strictly a lesser-of-two-evils decision in both cases and a question of which one I felt was least likely to cock up things more in 2016 and 2020. Both of their first terms wound up on a pretty sour note to say the least. I for one won’t vote for either one of them again. If these two “men” are the best the system can offer the people, I’m ordering off-menu. And will likely do so the rest of my life unless the two parties regain their sanity and dignity. The two-party system is a big problem and problems don’t offer solutions for themselves. Old keys don’t unlock new doors.

“We Won’t Get Fooled Again!” ~ you know Who

For at least a decade now, Republicans and Democrats have worked hand-in-hand with the increasingly invasive and alarmingly partisan media outlets to instill in the citizenry a constant sense of dread and crisis and a never-ending state of emergency that supposedly can only be resolved with the election of their chosen leaders. With a heavy assist from the hideous and hysterical nonculture of the internet, we as a nation have become addicted to division, intolerance, outrage and even outright hatred for one another. And we have allowed this sickness to take deep root as we continue to fan the flames of division. This inflamed partisan rhetoric also continues to distract us from the many true wolves at the door, threats that are so horrible as to be unthinkable both for our nation and the entire world. We are indeed at a cataclysmic crossroads as election time approaches, but to a degree in which the election itself may prove largely irrelevant. At the end of the increasingly darker day, I find many other things in the world far more troubling and worrisome than the question of which demented elderly man will run the country into the ground for a few years. As always I try to remain cautiously optimistic but my faith does not reside in a corrupt and irreparable two-party political system. Isn’t one definition of insanity repeating the same actions again and again while expecting different results?

“Activism” (if you can call it that) such as that on behalf of the two candidates in question is not inherently a good thing and does not necessarily bring positive change. It rarely changes hearts and minds, especially in these troubled times. Kindness, compassion, charity, good will, tolerance, worthy grass roots causes, forgiveness, helpfulness, good humor, and real show-up-and-go-to-work activism, nonviolent activism against a system that divides rather than unites, just might do so. So I will practice these virtues and continue to try, against my strongest instincts, to love and respect my fellow man. And I will continue to fill my head with art, literature, film and music instead of the maddening roar of ill will. If that makes me politically disengaged, then, like Nero, I guess I prefer to fiddle while Rome burns.

Back in 1871, the poet Walt Whitman, who always thought outside the box as it were, offered up a hopeful prophecy of a resurrected, reunited America in his Democratic Vistas:

“Intense and loving comradeship, the personal attachment of man to man- which, hard to define, underlies the lessons and ideals of the profound saviors of every land and age, and which seems to promise, when thoroughly develop’d, cultivated and recognised in manners and literature, the most substantial hope and safety of these States, will be fully express’d.

“It is to the development, identification, and general prevalence of that fervid comradeship…that I look for the counterbalance and offset of our materialistic and vulgar American democracy, and for the spiritualization thereof. Many will say it is a dream, and will not follow my inferences: but I confidently expect a time when there will be seen, running like a half-hid warp through all the myriad audible and visible worldly interests of America, threads of manly friendship, fond and loving, pure and sweet, strong and life-long, carried to degrees hitherto unknown…”

Interestingly, in 1972 Allen Ginsberg used the above passage as the introduction to his apocalyptic poetry collection titled The Fall of America…

I’d like to also acknowledge here the recent passings of writer-director Robert Towne (Shampoo, Chinatown, The Last Detail, The Yakuza) and the actress Shelley Duvall (McCabe & Mrs. Miller, 3 Women, Nashville, The Shining), who along with the recently deceased Donald Sutherland (MASH, Klute, Don’t Look Now, The Day of the Locust) were among the key creative titans of the New Hollywood renaissance of the 1970s. They added greatly to my film viewing existence and will be sorely missed.

With all that said, I want to express my deepest gratitude for your time and readership this last year. I’ve been extremely humbled by the response to Thee Bat City Vangarde and have really enjoyed the time spent writing, editing, and posting here and the odd online interactions with some of you. I hope to be back at some point if in some new form, so please subscribe if interested. If and when I return here, I will likely upgrade this column to a paid-subscription-only format but if you are already signed up you will continue to get these communiqués for free. As always, share as you see fit. Drop me a line and stay in touch. And now for the final-for-now overlong essay…

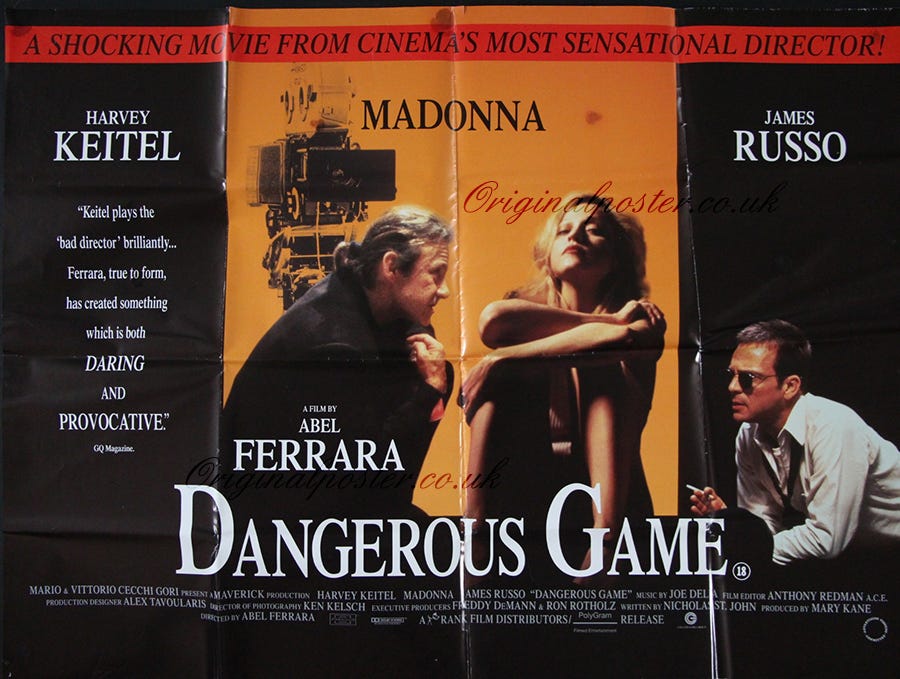

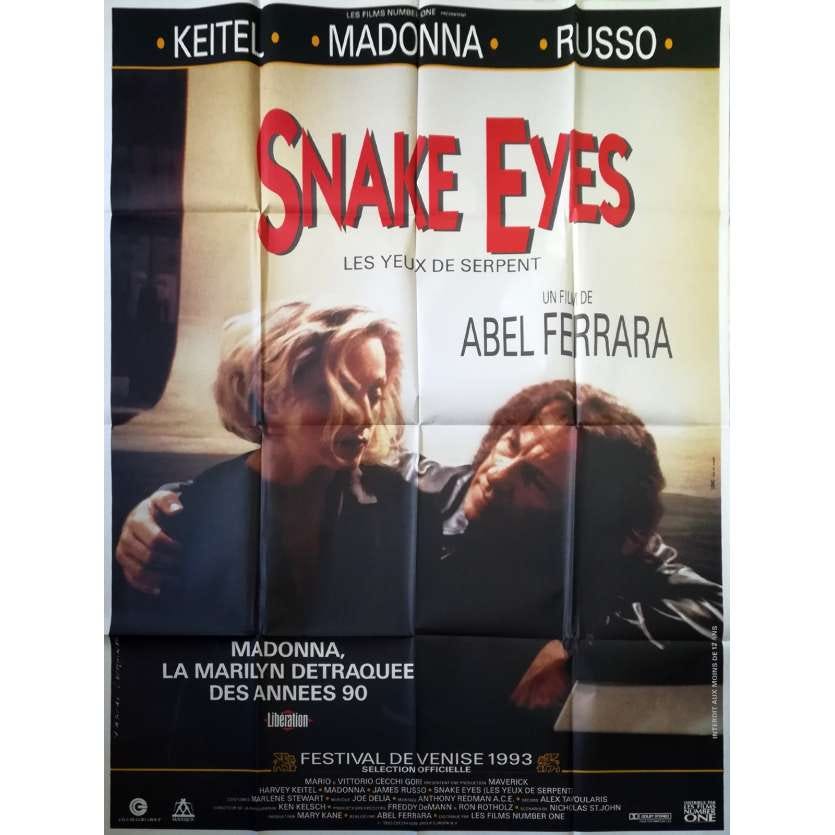

Tomorrow, July 19 2024, the brilliant and ever-edgy New York auteur Abel Ferrara will celebrate his 73rd birthday. Ferrara has long been one of my favorite filmmakers as well as an endless source of fascination and inspiration to me. I had a rather hilarious encounter with this underground King of New York Cinema back in 2001. I was in New York and had read that Anthology Film Archives was hosting a retrospective series of all Ferrara’s films to date with some screenings to be attended by the director and other notable guests. I was actually reading a biography of the filmmaker at the time and I was determined to fit at least one screening into my busy schedule while in NYC. As luck would have it, Dangerous Game, probably my favorite Ferrara flick at that point in the director’s career, was playing at a time I could attend, so Sherry and I headed to the Lower East Side to catch it. As we were standing outside the theater, a strange and disheveled hepcat Hop-frog street punk swaggered up to us with the damaged shaggy grace of a down on the heel jazz musician; he was immediately recognizable to me as the great Abel Ferrara and was accompanied by a burly leather-clad Hell’s Angels type. Apparently mistaking us for the theater’s management waiting to greet him, Ferrara extended a hand to me and said, “Hey bro, how ya doin’? I’m Abel.” I shook his hand vigorously and gushed, “I know who you are!” Then we followed Abel and his apparent bodyguard into the theater and I stood in the back and chatted with them until Ferrara moved to the front and introduced the film before quickly disappearing, presumably to ingest some form of illicit narcotic in the green room. I was still standing in the back of the theater with his crony when the film began rolling. While sharing its title with Ferrara’s Dangerous Game, this film opened with two clean-cut yuppies driving convertible sports cars on the Santa Monica Freeway and shooting each other with squirt guns and giggling. It was about as far away from an Abel Ferrara film scenario as one could possibly imagine. I whispered to Ferrara’s biker pal, “This is NOT Abel’s film.” He nodded, his jaw hanging down in disbelief. “You should probably go tell Abel what’s happening.” He agreed and set off to find Ferrara. A moment later, Abel barged back into the theater yelling, “What? Wait! Wait! Hold up, man! What the hell is this? What the hell is this shit? Turn it off! Turn this shit off!” The projectionist complied with the request and the house lights came up. Ferrara strode to the front of the theater loudly proclaiming, “Yep, that’s the best piece of work I ever did!” The audience erupted in knowing laughter. As much as I was looking forward to seeing the film I regarded as Ferrara’s masterpiece (at that time) on the big screen, the wrong Dangerous Game turned out to be something of a blessing in disguise, as Abel announced that he would instead screen his unreleased film The Blackout featuring Matthew Modine and Dennis Hopper. According to Abel, we would be the first American audience to ever see the film. It was a very good film, if not quite the Dangerous Game of which I wrote about a few years later as graduate student at Northern Illinois University.

Mother of Mirrors: The Film Within Destroys the Film Without in Abel Ferrara’s Dangerous Game

For Dr. Bob Self, beloved teacher and friend of Endless Irish Summers and Eternal Illinois Autumns.

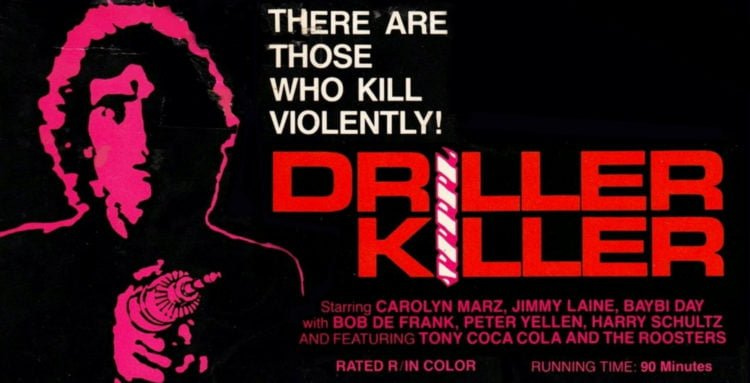

Introduction: The Arthouse/ Grindhouse Dichotomy and Evidence of an Emerging Style in Abel Ferrara’s Driller Killer

New York filmmaker Abel Ferrara occupies a singular space in the world of contemporary American cinema. His work reveals an innate distrust of any high art/ low art distinctions and presents a unique challenge to conventional notions of mainstream cinema practices. Effortlessly it seems, this streetwise hoodlum-auteur negotiates the terrain between “B-Movie” and “Art Cinema” sensibilities throughout his body of work, managing to yield a unique vision through these very contradictions. This particular style, at odds with itself, would seem to be at ease within the tensions of the harrowing visions he brings to the screen.

The narrative and themes of Ferrara’s films mesh effectively with his fragmented and contradictory style of cinematic expression. The films are moralistic, Catholic even, yet seem to revel in violence, sex, addiction and decay. They are hard-boiled, earthy genre films- horror movies, crime thrillers, drug films, etc.- full of profanity and graphic violence, yet also rich character studies that seem to reside in the interior spaces of their protagonists. He is deeply inspired by the work of international art cinema auteurs like Godard, Fassbinder, and Pasolini, yet his films consistently feature voyeuristic visions of misogyny and self-destruction that, coupled with bare-bones production values, resemble nothing so much as grindhouse pornography or amateur documentary. His dark visions seamlessly meld the New York sensibilities of the Vietnam War counterculture era with late 1970s punk rock vitriol and gangster rap attitude. Ultimately, his films largely fail to find a significant stateside audience, yet European cinephiles revere him while some of the best actors in the business compete to appear in his films.

In a practice more characteristic of European art cinema, Ferrara has continued to work, almost obsessively, with the same stable of actors, including Christopher Walken, Victor Argo, Willem Defoe, Paul Calderon, and David Caruso among others. The same holds true behind the camera, where Ferrara remains devoted to the same production crew from film to film, most notably pseudonymous screenwriter Nicholas St. John, who has penned eleven of his films and is rumored to be a Catholic priest. In practice and product, Abel Ferrara seems determined not so much to bridge the gap between art and exploitation cinema as to ignore the distinction altogether.

While the differences between the classical Hollywood style and that of an international art cinema have been elaborated by critics ad nauseum, it can be asserted that the two modes have more in common, in both art and artifice, than not. However, the strict demarcation separating both classical Hollywood and the art cinema from low-brow/exploitation fare has traditionally been unassailable at least until New Hollywood directors like Martin Scorsese erupted on the scene with films like 1973’s Mean Streets. If directors like David Lynch and Quentin Tarantino have begun to further erode this distinction, they owe something of a debt to Abel Ferrara as well.

The Driller Killer, Ferrara’s first feature film (discounting dabblings in the porno industry) appeared in 1979, and the seeds of his unorthodox style are on disturbing display throughout. The film would fit comfortably on a double bill with either of two contemporaneous films: Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1975) and Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), both of which, it should be noted, share the same arthouse/grindhouse dichotomy as Ferrara’s films). Just as Scorsese brought a European neorealist and New Wave sensibility to his gritty portrayals of New York City life- social commentary, subjective and psychological perspectives, location shooting, ambiguity, lack of narrative closure- so Ferrara continues in this tradition. However, Ferrara allows his urban angst-ridden noir to descend much further, into the realm of the drive-in splatter film, blurring the boundaries of traditional hierarchies of cinema in an even more aggressive manner.

Like Scorsese's Travis Bickle, Ferrara’s Reno Miller (played by the director himself) is a character suffocating in the squalor and paranoia of his New York urban environment. A down-on-his-luck painter, he descends into madness due to an overwhelming fear of soon becoming one of the homeless people he encounters daily on the Lower East Side. He counters this fear by destroying its source: murdering homeless men with a power drill. The film was produced during the homeless crisis of 1977 and utilizes actual footage of such victims captured by Ferrara’s crew. In this respect, The Driller Killer is a cheap horror film with a depth of social consciousness and a documentarian agenda. It also contains many of the stylistic devices, themes and motifs that recur throughout his later films: The color red, Catholic iconography, lesbian sex scenes, close-ups of breasts, an obsession with redemption and damnation, noir-esque cityscapes, eclectic musical scores, drug use, the juxtaposition of high art and low art film practices and imagery, and, of course, extreme acts of carnage.

The Driller Killer both begins and ends arbitrarily. There is no beginning and no end in his purgatorial vision. The viewer is thrown into Reno’s disoriented mind without aid of establishing shot or exposition and leaves it the same way. The lack of any viewer-friendly establishing shots persists throughout the film. The film opens inside a church, where Reno encounters a disheveled, apparently homeless man who may be his father, but this is never clarified. He runs from the church in fear; we are not sure why. The red color motif is established in this opening scene and recurs throughout the film.

After a cab ride in which he fondles his girlfriend, they arrive at Max’s Kansas City, the legendary punk club. The scenes here and those later of Reno’s rock band neighbors rehearsing, reinforce the documentary feel of the picture. Indeed, it is a documentary of sorts on many levels: The homeless crisis, the NY punk rock and art scenes of the 1970s, the guerilla-style location shooting of the old grimy Lower East Side locations (including the interior spaces which are the actual apartments of Ferrara’s “gang” who compose the cast and crew), and finally, the pseudo-autobiographical nature of the piece. Ferrara’s character Reno is actually based on his friend, the artist Metro, whose paintings appear throughout the movie as a motif. Additionally, it is Metro himself who plays the obnoxious punk singer, Reno’s neighbor and nemesis. Reno, the struggling painter, a paycheck away from joining his demons on the street, certainly reflects Ferrara’s status as an impoverished underground artist at the time of the film’s production. A scene in which a man is stabbed by a mugger is filmed from a rooftop and was obviously staged in the style of a prank, with real New Yorkers looking on, shocked but not wanting to get involved, as the actor lies in the gutter apparently bleeding to death. The scene is overtly reflexive in that Reno watches it from a roof with a pair of binoculars. The voyeurism of director, character and spectator are complicated and blurred.

The narration of Driller Killer is largely an interior monologue, with the settings and situations perhaps acting as metaphors for Reno’s detached paranoia, inability to communicate and growing madness. There are few hints as to the passage of time in the film. His apartment, which he shares with his girlfriend and her female lover who has apparently replaced him in the bedroom, represent the dissolution of his tormented psyche. Once a refuge for his creativity, he is now haunted by his work, the painting he cannot finish acting as the source of the instability of his continuing livelihood. The punk rock band that moves into his building oddly enough represents the successful, self-sustaining artist he has failed to become. The bums he murders may be figments of his imagination, or a very literal attempt to kill what he most fears, his descent into utter destitution and madness. Adding to the ambiguity is a bizarre dream sequence (recalling a similar device in Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby, which had defined the paranoid New York horror film for years to come) in which we meet another man who may or may not be Reno’s father, accompanied by garbled snatches of conversation and religious chants. Nothing is spelled out, as if most of what goes on in the film is filtered through the fractured mind of Reno.

The film contains a number of visual motifs. Slogans appear throughout that comment, at times humorously, on the proceedings. Before the opening credits, a graphic informs the viewer that “THIS FILM SHOULD BE PLAYED LOUD”, an allusion to both Scorsese's concert film of The Band as well as a common slogan found in punk album art of the time. In the opening scene in the church, a sign is framed in the background that reads “THERE IS ALWAYS TIME TO PRAY”. A glimpse of a newspaper headline informs Reno and the viewer that the “STATE ABANDONS MENTALLY ILL TO CITY STREETS”. At the scene of one of the murders, a poster reads “NEW YORK ALWAYS WINS”. The color red dominates the cinematography, as it will in Ferrara’s subsequent work. There is also the recurring visual motif of the staring eye, evidenced by that of the buffalo in the unfinished painting that torments Reno, and in the dream he has preceding the murders, in which the drill seemingly meets his own eye. The rabbit carcass which Reno sadistically butchers on the countertop stares up at him hauntingly, repeating again the motif of the staring eye, but also referencing Roman Polanski’s Repulsion, a similarly claustrophobic tale of horror and madness that flirts with both art and exploitation.

A bizarre and eerie musical cue accompanies Reno’s obsession with the eye of the buffalo, resembling the barking of dogs. The eclectic music soundtrack includes baroque Catholic organ music, a Bach piece, an electronic score by regular Ferrara collaborator Joe Delia, and the punk rock of Max’s Kansas City and Reno’s neighbors. A scene near the end (as opposed to resolution) of the film highlights its unorthodox use of sound. As the camera tracks slowly in to a close-up of the sleeping Reno’s face in profile, beautiful and calming music plays over the sound of a phone off the hook (recalling Reno throwing the phone out the window in the opening scenes). Intercut with Reno’s profile in peaceful repose are flashes of him bathed in red light and blood, brandishing his drill and screaming in rage. It is one of the great highly stylized sequences in the history of low-budget film.

Not unlike the masterpieces of international art cinema, Driller Killer is a puzzle for the viewer to decipher throughout; so much so that it has too often been casually dismissed as a rather bizarre example of bad B-movie filmmaking. This is not surprising, given its splatter-film premise and marketing campaign, not to mention stripped-down production values. In the end, however, it marks the earliest example of a master stylist finding his voice and unafraid to tread the murky waters separating European art and American trash. This tendency of Ferrara’s would seem to reach its fullest expression almost two decades later with the director’s 1993 autobiographical opus Dangerous Game.

I. Narrative and Style

As Fellini’s 8 ½ has come to exemplify the complexities of the “film-within-a-film” narrative form, Abel Ferrara’s Dangerous Game (aka Snake Eyes, 1993), which employs the same “hall of mirrors” reflexivity and autobiographical rendering of the filmmaking process, can readily be considered the dark flipside of Fellini’s seminal meditation on art and life. Both films blur the distinctions between the film itself and its own creative process; both are mid-career/ mid-life crisis films with actors associated with the work of their directors essentially “standing in” for them (Marcello Mastroianni in 8 ½; Harvey Keitel in Dangerous Game); and both films employ a fragmentary discourse to convey the dissolution of their protagonists’ mental state. But where Fellini’s film concludes on a hopeful note with Guido’s muddled filmmaking journey leading to self-reconciliation and spiritual/ artistic regeneration, the director of Ferrara’s “inner film” wields a dark mirror that reflects the hidden ugliness of the “outer film”, corrupting, nullifying and destroying the film without as the film within takes its nasty shape and infects its host.

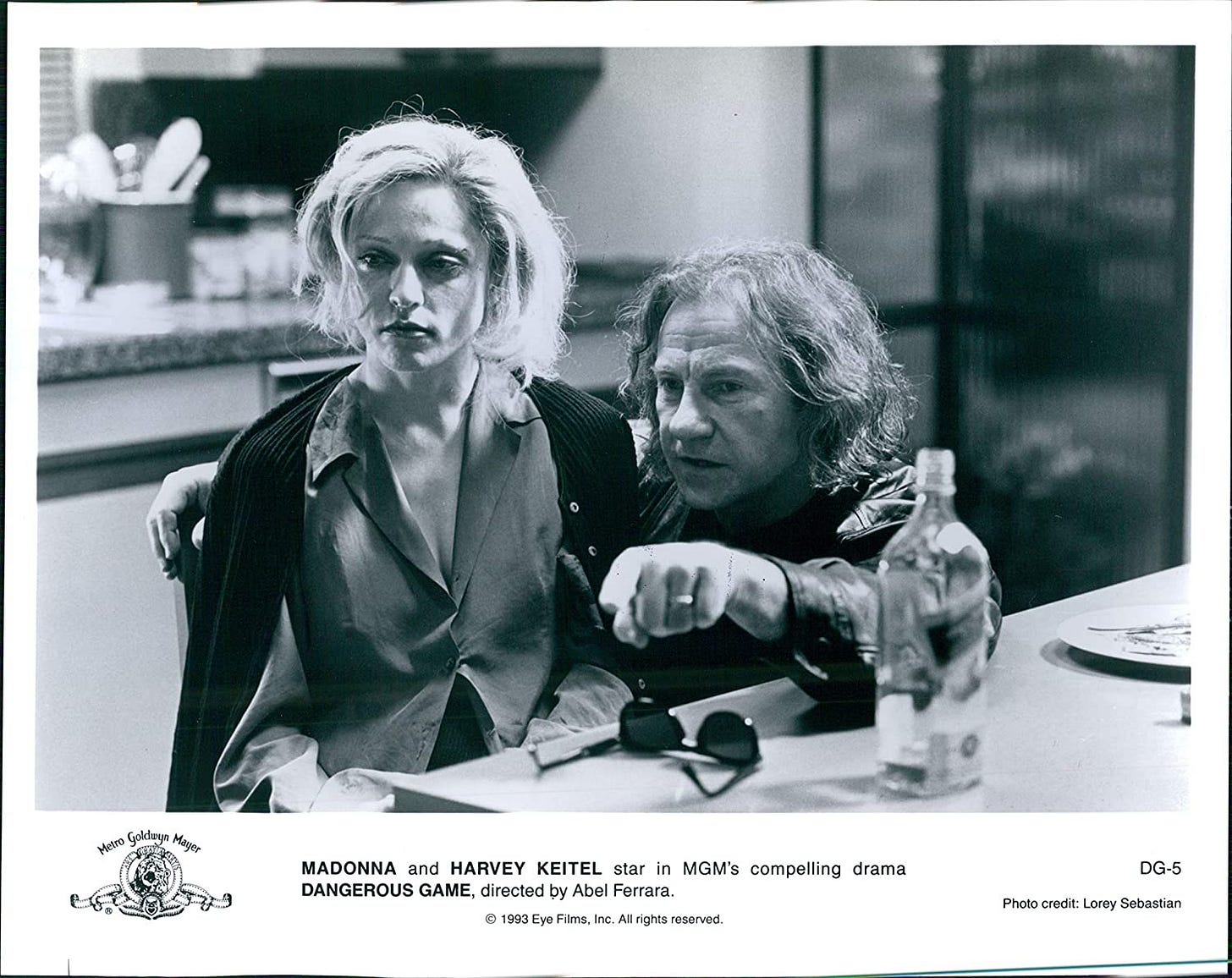

The opening scenes establish the fragmented narrative discourse that pervades the film. Dangerous Game begins with a quiet idyllic family dinner at home with Eddie Israel (Keitel, very much resembling Ferrara with his long, shaggy greying locks), his wife Maddie (Ferrara’s then-wife Nancy) and their son Tommy. Eddie is about to leave for Los Angeles. He and Maddie make love, then he visits his sleeping son and whispers “Don’t forget me, kid. I’m your daddy”. He walks down the snowy New York boulevard to presumably catch a cab to the airport.

The white on black opening credits which follow are accompanied by a voice-over in which Keitel/ Israel informs a woman (and the viewer) that he is making a new film and persuades her to sing “Blue Moon”, establishing a shift from Ferrara’s usual red color motif. Next, in stark contrast stylistically to the New York sequence, is a grainy, handheld cinema-verite segment in which Israel, in shaky close-up, waxes poetic upon the narrative and themes of his new film “Mother of Mirrors” as if for a “making-of” television documentary. A graphic at the bottom of the screen reads: “L.A. Rehearsals”. The character of Claire, he says, has found her “old life” of sex and drugs to be a “lie”; she has had a spiritual conversion and discovered a new “truth”. Another documentary-style scene follows, with Israel and crew setting up on a soundstage and Frank Burns, who will play Russell (James Russo), reviewing the script. Whereas the previous segment has the feel of an interview on a television monitor, this “backstage” footage has an immediacy that suggests unmediated observance of actual events by the viewer or by a documentarian.

The viewer is then thrown into the “Mother of Mirrors” film diegesis, with Frank’s character Russell menacing his wife Claire, played by actress Sarah Jennings (Madonna), while trying to persuade her to return to their swinging, drug-fueled lifestyle (“You should have been Mother Cabrini… instead of a middle-class pill-popping neurotic!”) Ominous music plays on the soundtrack and a blue haze envelops the proceedings as if to call attention to the artificial nature of this inner film and the movies in general. The inner film world is suddenly shattered by a return to the doc-style “backstage” footage as Eddie coaches Frank to intensify his performance. Back on the soundstage, Frank and Sarah continue rehearsal. Speaking his lines as he pulls her toward the bathroom mirror, Frank states that the eyes are the windows to the soul: “So let’s see what happens when you step in front of the mirror”. As they move to stare at their reflections, the narrative shifts abruptly from the actors playing their parts on the soundstage back to the alternative world of the characters of “Mother of Mirrors”. Frank/ Russell now wears a suit and Sarah/Claire wears eyeglasses (another mirror/ mask) and the haze and soundtrack music have returned. As Russell holds Claire and terrifies her, the camera zooms in slowly, removing the backs of their heads from the shot and filming only their reflections in the mirror, asking the viewer to question fundamental notions of reality, performance and identity. Driving the point home, the narrative suddenly jumps back to the “Rehearsals” documentary footage, with Eddie discussing the Claire character with Sarah in the dichotomous terms of spirituality and carnality and heaven and hell, each analogy the reverse mirror image of the former. As he attempts to clarify a point, he defers to someone off-camera named “Nick”, obviously the screenwriter Nicholas St. John who has penned the majority of Ferrara’s films, Dangerous Game included. This adds a further dimension to the doppelgangers discussed thus far. There has been the doubling of directors Ferrara and Israel, wives Nancy Ferrara and Maddie, actors/ characters Frank/ Russell and Sarah/ Claire, and the blurring of the film Dangerous Game with its inner film “Mother of Mirrors”, as well as various behind-the-scenes segments of the latter that seem to exist in a documentary film of their own. Now it stands to reason that this segment is actually footage of actors Harvey Keitel and Madonna discussing the Dangerous Game script with St. John and not part of any constructed fictional narrative. A later “backstage” segment has Israel discussing a shot with an off-screen “Ken”, an obvious reference to Ferrara’s steadfast DP Ken Kelsch. Furthermore, various scenes on the soundstage are framed with shots of take-clappers, one of which reads “A. Ferrara K. Kelsch Dangerous Game” rather than “E. Israel Mother of Mirrors”. Such infinite mirroring leaves the viewer forever uncertain of which reality, or how many, the film is seeking to convey.

The next sequence of “backstage footage” is titled “Principle Photography” and begins with Eddie coaching Sarah. Once again, It is soon revealed that it is reflections in the set’s bathroom mirror that are being filmed rather than the characters themselves. Eddie is trying to coax Sarah through a meltdown brought on by the demanding nature of her role. He eventually exits the frame to direct from off-set and the viewer is left with Sarah crying and screaming for direction. It would appear that this is actual behind-the-scenes footage of a very real Madonna reaching her own breaking point. Later scenes, as well as the previous ones referencing St. John and Kelsch, support this reading. This sequence, in which the camera maintains its fixed position, often keeping her head out of frame, finds the pop star working beyond her usual acting ability in emotional power. There are constant references throughout the film to Sarah being a “bad actress” and a “commercial” commodity and it would not be unreasonable to assume Ferrara cast the singer for these associations.

The scene abruptly shifts back into the “Mother” diegesis, the mirror literally exploding and the backstage storyline replaced once more with the inner film narrative’s stylistic haze and eerie musical score. Again, it is the mirror rather than the actors that is filmed. Russell’s face is bathed ghoulishly in a flashlight beam as he delivers a monologue about the hypocrisy of Claire’s religious conversion, a perverse demon tormenting her for her spiritual aspirations.

With all the doubling and blurring of characters in the film, it is only James Russo /Frank Burns/ Russell that maintains a distinct consistency throughout. He is pure sadistic evil on-set and off and his sadism and self-destruction prefigures the downward spiral that Eddie Israel will descend into as he makes his film. Burns, like Russell whom he portrays in “Mother”, is a desperate, drug-crazed, promiscuous and violent alcoholic. It is suggested by both Eddie and Sarah that he lives this way to remain in character; however nothing in the course of the film leads one to believe he is capable of any other behavior. This unknowable aspect of the character is very much in keeping with the enigmatic actor who portrays him; James Russo is a powerhouse actor who despite an incredible body of work has remained a mysterious unknowable presence in film lore. What we do know is that Frank seems most alive when allowed to slap Sarah around and butcher her hair with scissors; he appears to relish the degrading invective he hurls at her. His violent misogynistic nature is socially sanctioned and normalized under the cover of Ferrara/ Israel’s “art”. When Frank is in bed with Sarah and talking to Eddie on the phone, he tells the director she is a “whore” that can’t act. She responds, tellingly, that he has had sex with “a girl in a script” rather than Sarah herself, and angrily departs. Frank then goes into another room where a jealous female coke-dealer has apparently been waiting for him. She berates him for his rude behavior and he slaps her around to get his drugs. Later, in a violent outburst on the set, he calls Sarah “a piece of shit” and berates her acting ability after abruptly cutting a scene in the middle. “You’re not on TV now, bitch!” he screams, another veiled slighting of Madonna’s pop icon status and acting ability. He accuses her of “not (being) there”, literally failing to reflect his performance. Israel throws him off the set and counsels him in his trailer (after throwing Frank’s cronies out, essentially clearing the set a second time), telling him to do more drugs and booze, or less, for the sake of the film, and reminding Frank that the “Suits” didn’t want him in the picture. This threat to Frank’s livelihood is then incorporated into his performance when Russell rants about losing his high-paying job. Finally, Frank, with Eddie’s apparent collusion, will (it seems) literally rape Sarah on film as the crew looks on in bewildered discomfort. Eddie encourages Frank to “Do it!” as Sarah screams in apparently real pain. Like Madonna’s breakdown, Russo’s entire performance seems too real and unsettling to be simple acting, and one is left to wonder as to the motivation behind Ferrara’s casting choices and what the director’s filmmaking process actually consisted of.

Following the apparent rape, a distraught Sarah yells that Frank can’t act and has to do everything “for real”. Eddie tells them that the scene is over and she cries “No it’s not!” The inner film and the “real life” of the outer film have become inextricable at this point. The next scene is a quiet intimate conversation between Eddie and Sarah as she recounts another rape earlier in her life that resembles too closely the inner story of Claire and Russell. This sensitive Eddie appears in marked contrast to the director who has pushed Frank Burns to his breaking point and harmed Sarah in order to achieve new depths of cinematic depravity.

As the production progresses, Eddie seems to take on more and more the viler aspects of Frank/Russell’s shared personality. Frank is the embodiment of Eddie’s own sinister impulses which the production of “Mother of Mirrors” brings to the fore. The distinction between the outer film and the inner is quickly eroded. The “Mother” performances are no longer in a separate diegesis with accompanying musical motif and the haze of artifice. They are incorporated into the backstage segments, with cutaways to Israel on set often interrupting the scenes to direct and comment. He is now embroiled in this realm, not outside presiding over it. The inner film has slipped beyond his control and he has become but another actor within it. Power chords, dollies and microphones now crowd the frame as the actors work, and the technical jargon of crew members is often overheard along with Eddie’s intrusive direction (“That’s right, she’s not there”, as Frank collapses with emotional intensity). Art is no longer separate from life, the world within has expanded to swallow the without, or perhaps the real world has come to dominate the world of artifice.

The TV-documentary style segments continue throughout. In one of these, Eddie tells his actors that Frank is essentially saying “You’re gonna serve God or me”, reflecting Eddie’s own (and Ferrara’s, we may assume) megalomania disguised in the role of film director. “The ultimate is to feel pain and suffering because then you have a chance to survive.” In Israel’s impassioned pleas for Frank to “dig down to hell” for his performance, there is the implication that Keitel/ Israel directing Russo/ Burns is but an extension of Ferrara directing Keitel. Furthermore, Ferrara references his previous collaboration with Keitel, Bad Lieutenant both generally in Eddie’s spiritual dissolution through drugs, spiritual vacuity and despair, and specifically in the final moments of the film, when Israel sways deliriously in front of a window talking to himself, a virtual copy of a scene in their previous film. The narrative also pays homage to Mean Streets, one of Keitel’s earliest works for Martin Scorsese (whom Ferrara admires and is often compared to), in a scene in which Israel recounts a surreal sex act mingling blood and semen just as Keitel’s character Charlie does in the earlier Scorsese film. Documentary-style footage late in the film has Israel/ Keitel recounting his days in the Marines, but this is Keitel’s own story, one he has told in various interviews. Thus Eddie Israel morphs not only with Ferrara but with the legacy of the actor playing him as well. Just as Madonna and Russo are made synonymous with the two characters they each portray, the tripling of Eddie Israel includes Keitel as well as Ferrara. As these examples demonstrate, the actors themselves here become as intrinsic to the narrative as the “characters” they are portraying. Each of the three characters embody a kind of unholy trinity of personas, one of which is that of the famous actors themselves.

The mirror motif so obviously delineated in the inner film’s sequences is given a variety of expressions in the outer narrative. There are countless references to dichotomies, doubles, fragmented identities and keeping the world at bay. A conversation in a restaurant with Eddie, Sarah and some Hollywood types is dominated by such allusions. Eddie asks why everyone in L.A. wears sunglasses to which Sarah replies “Because we know how ugly everyone is”. Richard Belzer is trying to fund his film, a script which he wrote “himself”, but with “someone else”. A woman reveals that her father was married to both her mother and her grandmother. A cutaway shot features a gaggle of superficial Hollywood fashionistas making the scene at the crowded bar, striking poses in their sunglasses and finery. L.A. is all mirrors, deception and surface. After making love to Eddie, Sarah abruptly departs in the same manner she had previously ditched Frank, drawing a direct parallel between the two men. Television screens dominate the discourse in unusual ways that suggest no real difference between what is on the screen and an objective reality. Eddie is often seen watching dailies on two or more screens at once, seemingly needing many “mirrors” to filter his art and reflect reality. Even off-set, his world is constantly mediated by film images . A party scene features several cutaways to a televised boxing match, but these insert shots are presented without a border to convey that the images are in fact on television and the TV they supposedly play on is never in shot. Additionally, in one “Mother of Mirrors” sequence, Russell plays a sex tape of Claire on the TV insisting that there lies the “real Claire”.

New York City and Los Angeles comprise reverse images and dichotomies of Eddie’s world. New York is snow, quiet streets, privacy, health, stability, family life and the “real world”. The scenes there feature a calming classical music piece that seems to be diegetic. Los Angeles is sunshine, public sphere, traffic, crowds, decadence, superficial relationships, chaos and the artifice of movies, all to the pulse of garish neon and gangster rap. Eddie succumbs to the seedy appeal of L.A. and begins wearing dark glasses at all hours and steadily partying. His “real” New York life intrudes on his new existence in the form of a surprise visit by Maddie and Tommy. They arrive with their own “set” of clothes and luggage, invading Eddie’s space (both physical and psychological) and Hollywood lifestyle. He initially tries to play the part of family man, but is unable to reconcile the two realms and shuts his family out of his life by ignoring them and watching dailies. Maddie accuses him of being “so California”.

As Russell tells Claire in “Mother of Mirrors”, “You’re dying to confess every…thing you’ve done…I ain’t ready to bare my soul to nobody!” Moved by self-loathing, Eddie decides to confess his countless infidelities and substance abuse to Maddie in New York. Whatever questionable good intentions he may harbor, he chooses to confess to her on the day of her father’s funeral as he can’t live the “charade” anymore. He once more enters his sleeping son’s bedroom, but is now unable or unwilling to remind him that he is his father. Violently rejected by Maddie, he is soon on a plane back to L.A.

As Dangerous Game draws to its conclusion, Eddie Israel is alone in his hotel room with only a female admirer and images of his film on various monitors for company. The shooting has apparently wrapped and the cast and crew have gone home, his wife has left him and he wastes his days and nights in a drugged stupor, hallucinating and talking to himself. The “Mother of Mirrors” filming has destroyed his life by exposing his corrupt soul to the daylight. Frank and the film can no longer substitute for his own depraved impulses. No longer able to hide his nature behind the status of film director, he has reached a point of no return and, like Frank/ Russell, must now live out his dark cinematic visions in life instead of art. The footage he watches suggests that his actors have been destroyed by the film as well. The images grow more and more harrowing. and it becomes apparent that it is Eddie, not Frank, who is Sarah’s true tormentor as well as his own. He yells at her, calling her a “commercial piece of shit” (now using the very language of Frank) and informs her that she needs him, he doesn’t need her, just as he no longer needs Frank to stand in for his own troubled soul. Madonna’s shocked reaction to Eddie’s vitriol again suggests an exchange that was unscripted. Cruelly playing the role of Frank/ Russell himself, Eddie finally badgers Sarah into achieving the line-readings he desires. He wants her to somehow truly and fully become Claire (“I asked you to throw the script away and give me something from you…You just gave me the script again!”), just as both he and Frank have come to embody the role of Russell and his life and the world of the film have become hopelessly and tragically enmeshed. The soundtrack of the footage with Eddie screaming insanely at his actors carries over into cutaways of Eddie watching a film being shown on his plane ride: “Why don’t you pick up the knife and stab this fucker! Who…is Claire?!” The footage on a monitor then shows Frank with a straight-razor to Sarah’s throat. Eddie’s voice says “cut”, but Frank keeps the knife to her throat, dragging her across the set as the crew erupts in chaos. Eddie’s voice is heard yelling to Frank to let her go. Seconds later, as Eddie viciously browbeats Sarah yet again, she refers to herself as “an actress who just got her throat cut”. Eddie reminds her that she is a very famous person and asks her if this is the image she wants to project to young girls, again blurring the icon Madonna with her cinematic alter ego(s) Sarah/ Claire.

The various narratives have simultaneously unraveled and converged. The last shot of Eddie is of him lying unconscious and alone in a pool of vomit by the toilet. This closes the outer narrative of the making of “Mother of Mirrors”. But there is a last visitation to the inner film’s diegesis, with its trademark music and blue smoke. Russell approaches Claire and points a gun to her head. There is a cutaway to Russell’s face as the gun fires, then he slowly walks away. Although the formal construction of this scene points to it being part of the film within the film, after all that has gone before it is impossible to know whether Frank has actually murdered Sarah. Claire/ Sarah’s final words to him before the gun goes off add to the ambiguity: “If you’re gonna do a scene like that do it when you’re sober.” The credits roll, this time with Bob Dylan singing “Blue Moon”.

While Fellini’s film-within-a-film ends with a circus and celebration, the director of Ferrara’s inner film is left with madness, death and despair. In the film’s final moments, as Eddie sits strung-out in front of the TV, the German film director Werner Herzog appears on-screen in an interview. “I shouldn’t make movies anymore, I should go to a lunatic asylum…I feel no happiness…”1 But the warning comes too late for Eddie, who has all ready rolled snake-eyes in the dangerous game called “Mother of Mirrors”. Film and life have swallowed each other and only oblivion remains.

II. Themes/Values

The essence of Dangerous Game seems reducible to two main thematic concerns: The fluidity of identity and the potential volatility of art. These two notions, like the mirror maze constructions of the film itself, are interrelated to a degree that at times makes one indistinguishable from the other. Is it an inherent instability of the human persona that yields an equally unwieldy art form that one is then unable to rein in and control? Or does the creative process itself act as a catalyst, producing such fissures and incompatibilities within the artist’s psyche and rendering him a hapless victim of his own creation? Ferrara, like Fellini and other auteurs of the classic international art cinema, is content to ask the questions while implying there are no easy answers.

It is impossible to say at what precise moment these characters and their doubles – in particular, Eddie Israel and Frank Burns – revert to, or embrace, the darker sides of their personalities. It is equally futile to wonder to what degree the Mother of Mirrors film shoot contributes to the downward spirals of all the central characters. It can only be assumed that the splintering of identity is inextricably bound up with some dark and unpredictable force lying beneath the piece of cinematic art on which they collaborate to produce.

As suggested above, the notion of a fluid identity in regards to Frank Burns/ Russell is suggested by the spectator’s inability to find a discernible difference between Frank the actor and Russell the character. The fluidity here is precisely a lack of difference. Unlike the public (director/ artist) and private (husband/ father) personas of Eddie (which eventually break down as we have seen) and the clear distinctions between the actress Sarah Jennings and her character Claire (although there is clearly not a distinction at times between the actress Sarah and Madonna, who plays her), Frank and Russell have at some point become a single unified sinister force. The viewer can only assume Frank has not always “been” Russell. He is at least a somewhat successful working Hollywood actor, and therefore must have some sense of responsibility and social decorum. The drugged out, violent and uncontrollable madman that he at some point becomes must conceal a former essential Frank, though what this man was like, or how similar he was to the character Russell, is impossible to say. Frank “acts” as a kind of meter to assess how far the film is spiraling out of Eddie’s (and Ferrara’s) control and taking on a life of its own. The production becomes a demon of sorts that brings to the fore the true frightening nature of the actor, perhaps against his will, and this same dark force destroys all it touches. Or is it the Mephistophelean director Eddie Israel who is orchestrating the dark forces?

The director is in charge of this creative process but equally a victim of its malevolence. It is difficult to reconcile the inversion of Eddie, his descent into Hell, with the man we are introduced to at the beginning of the film. He is a loving husband and father, as well as an ultra-cool and insightful filmmaker at the top of his game. His dalliance with Sarah and partying lifestyle can be excused as celebrity behavior, the price of fame. Shutting out his family is part of the creative process, the stress of the job. The duality of his nature is revealed so slowly, so subtly, that even his encouraging Frank’s substance abuse and tolerating minor violence toward Sarah may be written off as his efforts to create a more powerful and gripping film. But by the end of the film(s), he has allowed and encouraged Sarah to be raped and cut on camera, and perhaps even murdered. He has destroyed his family by revealing his infidelities to Maddie at the most inopportune of times. Finally, he is reduced to a delirious degenerate, alone with only his precious film footage and the nullifying comfort of various chemical substances. The viewer realizes almost suddenly that if this is in fact the same Eddie, he is a damaged corrupted one who has allowed his creation to twist him, and (through him) others, to its evil will. While Frank’s transformation, or infection, occurs off-screen, Eddie’s is at the core of the film but remains as hidden to the viewer, in a sense, as it is to himself. All the markers are there, but the clues can be baffling. In the end, the same questions remain. Is the director in fact the author of these tragedies or does the nature of a work of art determine the actions and behavior of those involved in its creation?

The twin themes are driven home by the fact that not only does the film within, Mother of Mirrors, refuse to be contained by its host Dangerous Game; but the host film is indistinguishable from its own creative process. If Madonna is Sarah and Keitel is Eddie, then it follows that Eddie the director is Ferrara the director as well. As delineated above, the narrative form and style of the film consistently blurs the lines between the film itself and its own production. The viewer is consistently forced to interpret the nature of the “realities” presented. Perhaps it is the unpredictable and uncontrollable volatility of making Dangerous Game itself that permeates and infects all that we see. The more layers of identity that are exposed , the more questions we are left with. The personas collide with one another and blend together until there are no clear-cut distinctions between actor and character, art and life. Harvey Keitel is at once the character and director Eddie Israel, the actor Harvey Keitel, and the director of all the above, Abel Ferrara.

It is then, perhaps, the force of a volatile art form itself that directs all these players, at once producing a cohesive, if utterly fragmented, cinematic vision while dismantling all notions of stable identity. Ferrara’s film, and life, veering out of control is the very subject of Dangerous Game, which therefore is inseparable from the inner film of Mother of Mirrors. The morphing identities of Eddie/ Frank/ Keitel/ Ferrara battle each other to produce a work of art. The art produced, by its very nature, destroys them, either by twisting their personalities into evil, ugly doppelgangers, or by revealing their true deformed and corrupt essences. Whether he was invited or just showed up to oversee production, Satan is clearly on the set.

The inclusion of footage of Werner Herzog in Ferrara’s film seemed to weirdly predict a minor controversy between the two radical auteurs many years later when Herzog was hired to direct a reimagining of Bad Lieutenant, Ferrara’s classic 1992 descent into hell starring Harvey Keitel. Herzog’s 2009 remake transplanted the original’s New York setting to the sub-titular Port of Call New Orleans and featured Nicolas Cage as its titular tarnished cop. When Ferrara got wind of the new film, he was outraged and typically profane and vitriolic in his statements to Filmmaker magazine about the situation, expressing his hatred of Edward Pressman, the rights-holding producer of both films and saying of Herzog, “He can Die in Hell.” Furthermore, Ferrara already had a beef with Cage due to the actor’s refusal to work with him on The Funeral back in 1996. I myself was pretty excited about the prospects of such a bizarre sharing of an unlikely film franchise between two directors I so deeply admired and while I liked Herzog’s version a lot, I ultimately I deemed Ferrara’s original to be the vastly superior iteration. When I attended Herzog’s Rogue Film School a few months after the release of his Bad Lieutenant, I asked Werner about the feud with Ferrara. Herzog rather outrageously claimed that he was completely unaware not only of the original film’s existence but was also ignorant of Ferrara’s work in general as well as of his own appearance in Dangerous Game, the film Ferrara had made with Keitel right after the original Bad Lieutenant.

Thank you for sharing your thoughts, writing, music and yourself. See you on the flip side. Until then...

Finally catching up a little bit on my reading. Enjoyed your article. Was very interesting and insightful.

You have a special gift for writing regardless how it came about. Your writing talent is and should be envied. Hope you will continue soon.