I know I am far from alone in grieving the loss of Sinéad O’Connor, one of the great innovators, evangelists, and peerless talents of (post)modern and traditional Irish music. Sinéad was a fierce punk priestess who seemed to embody the spirit of the cultural revolution that kicked off in divided Ireland in the late 1970s, and alongside the music of U2 and the films of Neil Jordan and Jim Sheridan, she became one of the country’s biggest international exports in the 80s and 90s.

As both an undergrad and graduate student I lived and went to school in Ireland for short periods, studying the country’s history, culture, literature, film and media and traveling throughout the island. I went on to teach Irish cinema courses at Austin Community College and the University of Texas, and Ms. O’Connor was consistently a topic in these classes. In 2013, I was invited by the Austin Film Society to curate and present an Irish film series. The following essay was written as program notes for the “Irish Punk Rock Double Feature” I hosted there one evening. I present it here with additional material in honor of the ethereal beauty and otherworldly talent that was Sinéad O’Connor. I hope you enjoy it and that you might raise a pint in Sinéad’s honor.

Ireland’s Punk Revolution:

THE LAST BUS HOME and IF I SHOULD FALL FROM GRACE

Troubles and Paradise: Notes on the Irish Cinema Volume 3

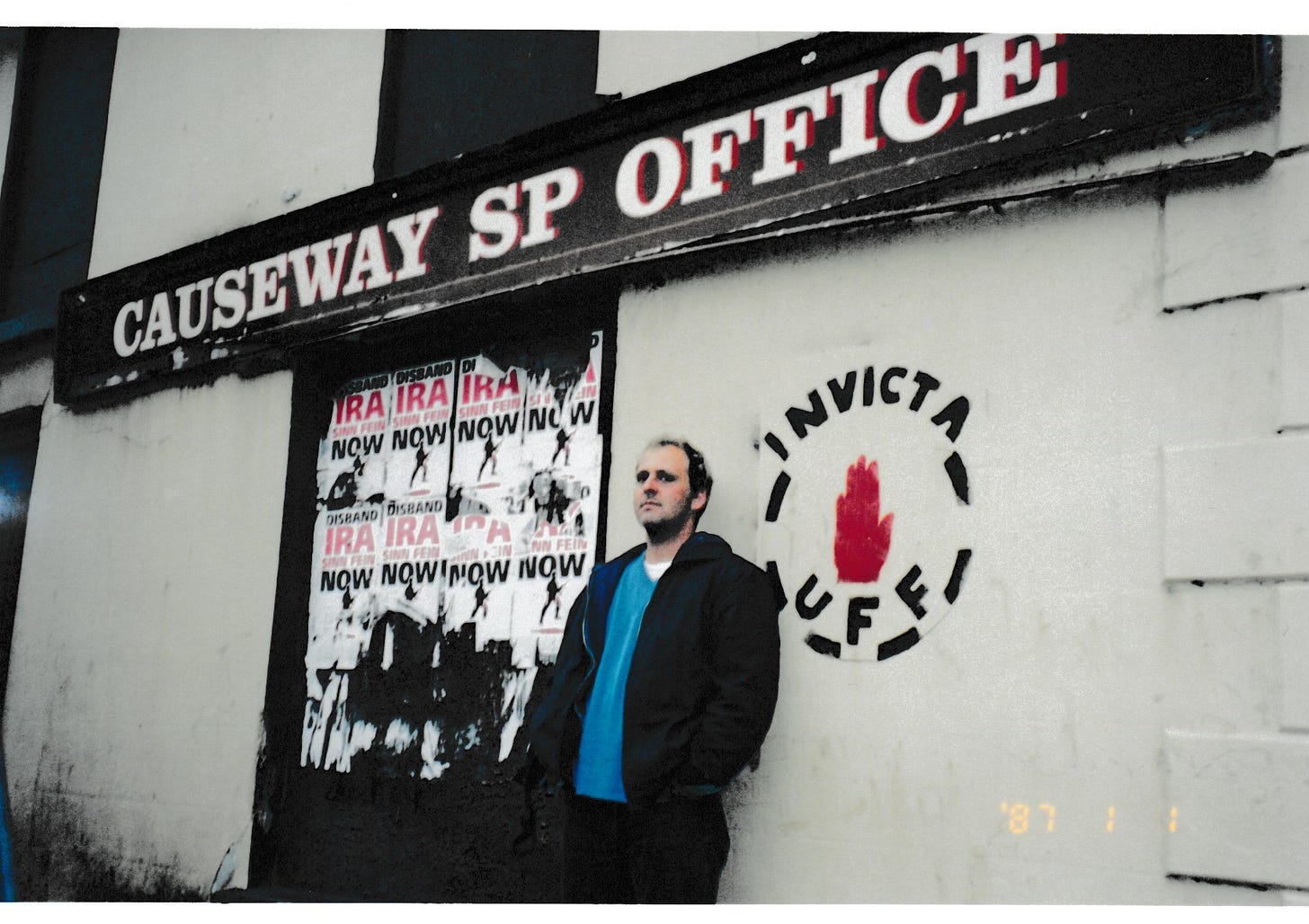

The author in Northern Ireland, 2001

People have always been storytellers I think, and the whole Irish song tradition has come out of almost a social role of passing information from village to village about horrible events, and has gotten sophisticated into a way of expressing emotion too. But it was mostly a kind of a historical documentary record: Disasters that happened, people who left for America…

~ Paul Brady

I think the Ireland out of which I was forced to explode was a very emotionally repressed place where everyone, especially women, were expected to behave very sweetly.

~ Sinéad O’Connor

The best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity.

~ William Butler Yeats

As a land synonymous with historical uprisings and revolution, it is tempting to see Ireland, with its close but troubled ties to England, as a natural environment for the vitriolic and subversive expressions of punk rock and its broader counterculture in the late 1970s and 80s. Traditional Irish songs of oppression, disillusionment and rebellion would seem a suitable medium for the angry, aggressive and politicized refashioning of rock & roll that followed the souring of the peace and love generation of the Sixties. But having missed out on the youthful 1960s cultural revolution that rocked the United States, Britain, and the western world in general, there was a unique sense of power and hope in Ireland’s early punk scene, an idealistic utopian vision that was more in keeping with the spirit of the 1960s than with the cynicism and nihilism of much of the punk coming out of London and New York at the time. The punk explosion of the late 1970s and 1980s acted as a sort of late arrival of the widespread 1960s counterculture for Ireland’s young, becoming the troubled island’s first significant youth subculture.

Like the nationalist poetry of W.B. Yeats in late 19th and early 20th Centuries, the Irish punk rock and New Wave movement was always harkening back to indigenous forms and traditions dating back to prehistory, mixing aggressive and socially relevant rock music with classical Irish influences and “trad” stylings. Often, what distinguished Irish punk from its counterparts in Europe and America was that it constituted a maintenance of the island’s folk tradition alongside a postmodern dismantling of it. Be that as it may, to misquote an old Irish song, it was a long way to punk rock Tipperary.

Following Ireland’s back-to-back wars of the early 1920s and the subsequent partition of the island, the new Irish Republic under Eamon de Valera’s leadership defined its arch-conservative government and social policies along traditional Irish values such as patriarchy, agrarianism, isolationism, antimaterialism, antiurbanism, and Catholicism. Efforts to ensure that the Republic remained an unspoiled, quasi-medieval autonomous zone free of modern western influence were rooted in a deep religiosity that was inherently tied to issues of Irish race and national identity, a situation that gave the Catholic Church leadership an inordinate amount of power and influence. Around the same time that Irish Catholics in America were implementing the Hollywood Production Code, the Censorship of Films Act of 1923 headed up by the conservative Catholic government of Ireland banned many imported films from the US and elsewhere based on their “morality;” while under the same laws, bans were also enacted on avant-garde literature and other “liberal entertainments” like jazz music. It was a fear of outside modernist influences that most fuelled Irish censorship laws, a concerted anti-colonialist agenda to keep the new country “pure” and to maintain its cultural traditions that dated back at least to the Gaelic Revival of the 1800s. Meanwhile the courtship rituals and entertainments of Ireland’s youth were rigorously scrutinized and supervised by both the clergy and the political establishment, creating tensions between the enforcement of morality and the longstanding traditions of singing and dancing that had defined Irish life from time immemorial.

Effectively shut off from the rest of the western world and existing in a state of media blackout, one result of such cultural policing was that until the 1940s, traditional Irish music forms- ceilidh, jigs, reels, rebel songs, romantic ballads, etc.- were the only musical entertainments to be found on a night out on the island. But in the 40s and 50s, the phenomenon of the “show bands” arose, composed of third-rate Sinatra and Presley knock-offs that toured the country and offered something approximating the contemporary popular music forms taking England and America by storm. To Ireland’s serious artists and musicians, however, the cultural exchange offered by the show-bands was far from a progressive step forward for Irish popular music. “Socially, the show-bands were important,” Irish punk legend and famed humanitarian Bob Geldof has stated. “Musically and every other which way, they were a death, which is why contemporary Irish music took so long to develop. And (when it did), it came out of the Irish tradition, vaulting over the years of the show-bands…The show-bands were crap! I thought they were an appalling travesty…” While show-bands offered the only game in town in the post-war years for young Irish musicians and singers aspiring to pop star status, Geldof’s comrade Bono has similarly commented that show-bands were “the enemy” to the next generation of local artists: “These people were from an Ireland that we had no interest in being a part of.”

While most Irish households did not own television sets until the 1970s, the country’s public radio and television network RTE was established in 1961 and a youthful Beatlemaniac pop culture soon developed that was largely in step with that of England and the US. While no widespread “youth scene” flourished due to the country’s enforced conservative values and continued restrictions on entertainment, as the decade progressed Dublin began to somewhat resemble a vibrant, youthful city like London, and the “Dublin Beat” scene produced a number of successful garage band imitators of the Beatles, Kinks, and Stones; with Van Morrison’s protopunk R&B outfit Them leading the pack. As the psychedelic era exploded across the pond and in America, Rory Gallagher took the aggressive guitar wizardry of Hendrix and Clapton and put his own distinctly Irish punk sneer into the imported stylings. Phil Lynott, a multiple minority within the hegemony of Ireland as a black man, a black rock and roller, and a drug culture exemplar, formed Thin Lizzy and further cemented elements of Hendrix, dirty blues and psych into the sonic realm of what would become known as punk rock while drawing on the Irish literary tradition and Celtic mythology for inspiration. Like Morrison and Gallagher, Lynott was determined to maintain artistic ties to Ireland’s long lineage of poets, storytellers, and balladeers, recording old Irish songs and publishing poetry books alongside rock hits like “The Boys are Back in Town.” He would go on to collaborate with both traditional Irish musicians and fellow punk pioneers including members of the Sex Pistols, the Boomtown Rats, and New York Doll Johnny Thunders before sadly, like Gallagher, Hendrix and Thunders, dying prematurely at the height of his career.

At the same time in the 1960s and 70s, there was a popular renaissance in traditional Irish music, with bands like the Dubliners, the Wolf Tones, and the Chieftains returning to the old ways and forging an inextricable bond between the Irish folk tradition and contemporary popular music. With the resurgence in popularity of folk groups and traditional music clubs, a band called Horslips emerged that officially inaugurated the Celtic rock genre. Combining the glam-punk sexiness and loud electric rock chops of Gallagher and Lynott with the jigs and reels of the Dubliners and Chieftains, the band initiated what was perhaps the Irish equivalent of “Dylan goes electric” with a similar reactionary backlash erupting among the island’s folk music purists. Still, the mingling of contemporary music with trad seemed to be the established norm in Ireland. “The kind of divisions that have existed or have developed in Britain to an extent, and the kind of fragmentation that’s taken place in America with all the different markets being defined; that hasn’t happened in the same way in Ireland,” says Niall Stokes, editor of Hot Press, the music and politics magazine established in Ireland during the punk era. “So there’s a kind of cross-fertilization of music.” Bob Geldof adds that “the musicians blend effortlessly…There was no sorta like hang-up in the country between pop musicians playing with traditional guys. It was cool… Irish balladeering was a highly potent social and political force. When you can’t express yourself through other ways, if you’re forbidden to; then, there’s a great subversity in ballads. They were often used as political broadsheets, from which you go on to the Dylan, folk, protest thing. They were often used to tell about the hard times, of which there were many…Irish music, far more than any other I can think of, even American music, is inclusive. There is no difference between traditional and contemporary pop. None.”

In 1975, the Troubles violently intruded into the local music scene when three members of a late-era show-band were viciously killed by a Loyalist murder gang in Belfast, resulting in the collective reluctance of internationally touring acts to risk playing on the island. Northern Ireland essentially became a no-go area for traveling musicians, greatly diminishing cultural exchange. Meanwhile the same economic and social malaise that pervaded merry ole England in the 1970s and which gave rise to the punk subculture there also blanketed the other British Isles. “The process of change that had been jump-started in the Sixties was now operating on two cylinders,” remembers Stokes. “We’d gotten a taste of cosmopolitanism, but it was as if the hatches had been battened down. For most of the Seventies, in cultural terms, Ireland was an isolated place. It was an era of economic taxes, an economic deficit that was rocketing out of control, and an allied sense of disillusionment and, for many people, despair.” Upon returning from an extended period abroad, Geldof found the cultural wasteland of mid-1970s Dublin bleak indeed. “Dublin was nothing! There were no jobs; there was no thought; it was oppressive! People still looked to me like the Fifties…I did come back with the sole intent of trying to change things…I never had a beef about Irish music. I had a beef about what had been rammed down my throat…I could see that Irish music could be used in a contemporary sense…There was a new Ireland to be talked about. Whatever we were doing, somehow it articulated that new crowd, who no longer wanted to be part of the prevailing ethos and morality and were moving on.” As U2’s Bono recalls, “We came from this place, this just gray concrete place, a lower middle-class ghetto of non-culture. The thing I remember most about growing up was violence.” Dublin DJ Darren McReesh remembers an Ireland “in the grip of uncertainty; conflict in the north, social conservatism in the south, both fueled by religious hegemony and a truly desperate economic situation. To be young in Ireland at that time was extremely tough, with many choosing to follow the well-worn path of emigration. For those that stayed, many had little choice but to join the dole queue. TV, radio and print were combining to fuel the imaginations and plant seeds of disaffection amongst an increasingly sophisticated and pop literate youth desperate for change. When punk entered the mainstream, the conditions were such that a hungry, culturally savvy new generation were perfectly primed to tap its latent energies.” Access and proximity to the emerging punk culture in England- John Peel’s radio sessions, magazines like NME and Melody Maker, independent record distributors like Rough Trade- added to the Irish punks’ yearning for similar social change and a widespread DIY creative scene to call their own.

Geldof soon founded the Boomtown Rats, an immensely popular and very Irish punk act that, along with fellow travelers like the Undertones and Radiators from Space effectively launched a musical youth movement throughout Ireland. While the Undertones made their mark internationally with the 1978 underground hit “Teenage Kicks,” the Radiators were considered Ireland’s first punk band, fronted by future Pogue Philip Chevron and also boasting the talents of Steve Averill aka Steve Rapid, who would go on to alternately form and collaborate with post-punk acts like the Modern Heirs, the Peridots, Tell Tale Heart (dubbed “Ireland’s first electronic pop band” by Late Late Show host Gay Byrne in 1979), and SM Corporation, an electronica act that released a cover of John Carpenter’s Assault from Precinct 13 film score in 1985. According to legend, it was Averill who suggested to the four young Dublin punks known as the Hype that they change their band’s name to U2, and he soon became the designer of the band’s iconic album artwork as well. The spirit of community and collaboration was a defining element of the early Irish punk days, and the intensity and excitement generated by artistic communion would nurture and sustain the growing scene.

Another good example of this kind of long-term mutual support is that of Gavin Friday, who despite a very successful career as a composer, solo artist, and all-around media visionary, still makes the time to collaborate with his superstar pal Bono on musical and film projects as well as on the massive undertakings that comprise U2’s touring machine. Bono and The Edge contributed guest appearances on Friday’s 1995 release Shag Tobacco, while back in mid-1980s, Bono and Friday shared an art studio in Dublin and exhibited their works together at the Hendricks Gallery in 1988. Most recently the two have partnered on a film and book adaptation of Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf. Apparently Bono and Friday also remain next door neighbors in Dublin to this day.

Thanks to the mainstream celebrity of the Boomtown Rats, Ireland’s punk acts suddenly found themselves in demand to play in Dublin’s bars, clubs and community centres. “There was a wave of energy that the Boomtown Rats definitely fastened on,” remembers Martin McGuiness, the Albert Grossman-like guru and manager of U2. “Not just in musical style (but in) the very aggressive, in your face alternative ways of bringing the band to people’s notice. Graffiti and public outrage and confrontation…” The anger and do-it-yourself ethos of punk was a natural fit with the bored, impoverished and disempowered Irish lads and lasses of the 1970s. Having largely been passed over by the 1960s counterculture, Ireland’s youth now had their own musical and artistic subculture, made by and for them. The raw, youthful excitement of the early Irish punk days defined by the Rats, Radiators, and Undertones left an indelible impression on a young Sinéad O’Connor. “I was mad into (the Rats’) first album…and Geldof was very sexy and all, in a way that Irish men in showbiz had never been.” Aided by progressive local magazines like Hot Press and Heat and the influential scene-chronicling fanzines VOX (which also launched a short-lived record label) and Imprint, a punk scene was soon flourishing in the island’s urban centers of Dublin, Cork, Derry, and Belfast.

In the North, a powerful band called Stiff Little Fingers melded raw yet melodic punk energy with thoughtful and serious social and political commentary to become Ireland’s own version of The Clash. Inspired by such slightly older contemporaries, four Dublin teens soon formed a little punk band called U2. According to Bono, seeing SLF play Irish punk anthems like “Alternative Ulster” and “Wait and See” was such a powerful experience that he locates “the beginnings of U2” in it. “And apart from the music, the atmosphere had another color to it, which was violence. It was like the cultural revolution…It was an interesting feeling because it was the beginning of punk rock…That’s where the idea formed in me that music is a life or death experience …That’s the way we felt about it; it wasn’t just entertainment.” Two decades later, U2 was now among the biggest bands in the world, but the quartet of charismatic Christian lads- two Catholic and two Protestant- insisted on playing shows in SLF’s troubled Belfast at their own peril in support of the Good Friday Agreement peace process referendum.

War torn Belfast was also the home of Good Vibrations, the legendary record store, gathering place, and record label run by Terri Hooley, who released the Undertones’ “Teenage Kicks” as well as records by the Moondogs, the Outcasts, Protex, Rudi, the Shapes, the Tearjerkers, and many other punks on the rise before declaring bankruptcy in 1982. Hooley and the Irish bands he loved, produced, and promoted- including the Outcasts, Rudi, Stiff Little Fingers, and Shane MacGowan’s early London band the Nipple Erectors- often took the stage of the Harp Bar, a social experiment which not only became one of the island’s first proper punk dives, but also created a Troubles-free social experiment where young Catholics and Protestants freely mingled under the utopian banner of punk rock and the shackles of sectarian tribalism were cast off by a new generation who wanted no part of the Northern conflict. Other venues like Belfast’s Glenmachen Hotel and The Casbah in Derry also hosted punk shows and nurtured the growing youth scene in the North (GOOD VIBRATIONS, a critically-acclaimed biopic about Hooley and the early Belfast punk scene was released in 2013). By the early 1980s the original Belfast scene was being ushered out by a new hardcore anarchopunk contingent that drew on the radical politics, alternative communities, and aggressive noise of British bands like Crass and Discharge for inspiration, creating a commune-like DIY scene in the City Centre. In 1981, an organization called the Belfast Anarchist Collective opened the Anarchy Centre which eventually included a bookstore, a printing press, a music venue, a rehearsal space, recording and photography studios, and a vegan café. In addition to punk gigs, the Centre also hosted political action groups, poetry readings, and many a party that lasted through the night. Soon taken over by the Belfast Gig, Belfast Musicians, and Warzone Collectives, the DIY space was rechristened the Warzone Centre in 1984. Although the space was relocated a number of times and shuttered for extensive periods, the Warzone Centre refused to die and miraculously survived in one manifestation or another until 2018.

The Undertones also hailed from the North (Derry) and provided one of the punk era’s essential classics with 1978’s “Teenage Kicks.” In a later appearance on England’s Top of the Pops broadcast, guitarist Damian O’Niell added a black mourning armband to his stylish punk couture for the ’Tones’ performance of “It’s Going to Happen!” The song addressed the highly controversial hunger strikes of IRA prisoners, while the black armband honored the fatal self-starvation of Republican martyr Bobby Sands.

Meanwhile, across the pond in London, the Sex Pistols injected a seething, aggressive Irishness into British punk. With his naturally red hair exaggerated to flaming orange, London-Irish youth Johnny Rotten namechecked the UDA and the IRA in the group’s incendiary 1976 underground hit “Anarchy in the UK” and followed it up with the sneering, mocking anti-anthem “God Save the Queen” just in time for the following year’s Silver Jubilee celebrations. It has often been overlooked that in the racist anti-Irish environment of 1970s England, what most likely made the Pistols cultural enemy number one was not simply the band’s anti-English and antiauthoritarian songs and outlandish appearance and shenanigans, but that Rotten’s menacing persona was so evidently coded as a volatile Irish hooligan preaching “Anarchy in the UK” and clearly out to dismantle the system. Under his birth name John Lydon, he would later tellingly subtitle his memoir Rotten, “No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs.” Patrick Deer, a critic and NYU professor whose work explores the interface of military culture and popular culture in Britain, suggests that the Troubles in Northern Ireland and the war between the Crown and the IRA were among the central themes that emerged in the first wave of British punk and that the pervasive media images of the conflict were among the great catalysts for the widespread apocalyptic music movement: “In the conflict-torn cities of Northern Ireland during the Troubles in the late 1970s, the anarchic growl of punk music confronted, in addition to the unemployment and aggressive policing that confronted youth on the mainland, both sectarian violence and a militarized state of emergency. Helicopter noise was deployed against demonstrators; surveillance technology listened for snipers and paramilitary plotting; white steam noise was used to break down internees. Yet, on both sides of the Irish Sea, bands like the Undertones, Stiff Little Fingers, the Sex Pistols, Public Image Limited, and the Fall pitched punk negation and artlessness against the sounds of militarized urban conflict with unpredictable results.” The Pistols had disbanded after one album and Lydon formed Public Image Limited (PiL), which combined the anger, disillusionment, and noise of punk with more avant-garde tendencies. PiL’s second LP in 1980 included the song “Poptones”, arguably Lydon’s most artistically accomplished and compelling musical track. Unfolding amid a dreamy, pseudo-psychedelic soundscape, the singer presents a scenario straight out of the Troubles through his abstract, impressionistic lyrics. A victim is kidnapped and secreted away by car to a peat-covered British countryside where, “lying naked in the back of the woods,” he sings to us from beyond the grave like a hardboiled punk noir protagonist “losing my body heat.” Meanwhile, from the mysterious assassins’ car, “the cassette played poptones.” “The references to abduction by car, to peat, and to burial in the rural countryside, as well as John Lydon’s London Irishness,” Deer writes, “suggest the political assassinations and disappeared bodies of those caught up in the Troubles of Northern Ireland…(and) are reminiscent of Seamus Heaney’s ‘bog poems.’” Often in more subtle ways, many other prominent British punk bands also invoked the ghosts of the Troubles and British militarism, including The Clash, The Jam and Gang of Four. The lyrics to British punk songs are notable for offering a vision of England as an apocalyptic urban hell, literally burning before the eyes of its young anarchist musicians as the fascist police machine tries to enforce its own brand of law and order among the chaos. Along with the rise of powerful right-wing movements, economic instability, and a rigid class system, the Troubles in Northern Ireland and England’s war with the IRA provided the suitably harsh sociopolitical environment that lit the fuse for British punk and allowed it to explode.

Inspired by the Pistols, a young Irish emigrant named Shane MacGowan would soon marry London’s raucous, subversive punk with, as he explains himself in tonight’s second feature, “extremely old-fashioned Irish music. Proper Irish music. People’s Irish music…Ceidleigh music, jigs, reels. Lyrics about drinking, fucking, fighting…Romantic lyrics about love and rebellion and whatever.” In addition to the rotten-toothed MacGowan on vocals, whom Stokes describes as “one of the wildest and most uniquely charismatic figures in popular music,” the large ensemble of the Pogues also included Dublin punk icon Philip Chevron from Radiators in Space, trad-punk tin-whistler Spider Stacy, and 1960s folkie Terry Woods, coming together to create the London-based musical project’s unique hybrid punk-trad sound. The Pogues’ ingenious fusion of Celtic folk and punk rock was quickly coopted in a more sanitized form by the New Wave movement of “Raggle-Taggle” bands that included the popular Waterboys and Dexy’s Midnight Runners.

Back in Ireland, the androgynous, Adam Ant-like Gavin Friday remembers a set of challenges for early members of the island’s outlandish punk subculture that would have been familiar to their British counterparts on the King’s Road, including skirmishes with related youth cults like the Skinheads and Bootboys and staring down the notorious Irish homophobia and fear of difference: “We couldn’t get served in pubs. Weird thing was we threatened blokes so much, but girls loved us…Wear a dress and every girl will love ya.” Friday and his young protégée Bono rallied a punk orbit around the goings-on of “Lipton Village”, a sort of imagined community and art project that manifested itself as a psychic then physical gathering place for an increasingly larger gang in the Ballymun suburb of north Dublin, eventually becoming “Punk Central” and Ireland’s equivalent of London’s King’s Road or the Bowery of Manhattan. Inspired by the gender-bending glam protopunk of David Bowie and T. Rex, Friday, formed the outré musical performance art group the Virgin Prunes in 1977, a brilliantly subversive band that helped launch the Goth movement and also included The Edge’s brother Dik Evans among its roster. Despite a degree of notoriety that included mainstream media coverage, the Prunes didn’t manage to release their first single on the band’s own Baby Records label until 1981.

While U2’s international success remains peerless in the annals of Irish popular music, for every Undertone, Stiff Little Finger, Radiator from Space, Virgin Prune, and Boomtown Rat tale of glory there are dozens of forgotten heroes. A short list of early Irish punk, new wave and electronica bands (often sharing personnel) includes relatively obscure acts like the Atrix, Blade X, Big Self, Chant! Chant! Chant!, Choice, the Faders, Flying Lizards, Kissing Air, Know Authority, Microdisney, Nun Attax, Of Xerox, Operating Theatre, Shock Treatment, the Sweat, the Threat, Tokyo Olympics, Tripper Humane, and Vipers, among those already mentioned and countless other scenemakers and subcultural engineers. The impish, enigmatic and Zelig-like BP Fallon certainly had a hand in bringing the legacy of the 1960s counterculture and serious rock & roll street cred into Ireland’s gestating punk scene. Fallon had already enjoyed a long and rather mind-blowing career in the music industry by the time the New Wave happened. Beginning as a radio and television personality on the Irish airwaves in the 1960s, he soon made his way to Swinging London as a journalist for Melody Maker and eventually became a member of John Lennon’s inner circle, leading to an appearance with Lennon on Top of the Pops and a publicist position at the Beatles’ Apple Records, where he sampled weed as the royal taster for Paul McCartney. He soon established himself as a strangely charismatic court jester to a wide array of rock royalty. By the early 1970s, “Beep” was the publicist for T. Rex and was credited with coining the term “T.Rexstasy”, the glitter rock equivalent of the Beatlemania phenomenon of the Sixties (BP is also actually name-checked on T.Rex’s 1972 hit “Telegram Sam”) . As a press agent, he represented the likes of Joe Cocker, King Crimson and Jimmy Cliff. During the same period, he became an intimate of Robert Plant and accompanied Led Zeppelin on tour (reputedly even performing a bit of percussion on 1969’s “Whole Lotta Love” and providing photo art for Zep's albums), while also celebrating his Irish roots as a publicist for Celtic glam protopunks Thin Lizzy. Like so many of Ireland’s younger generation, Fallon, with his penchant for zany outrageous couture (including his trademark Artful Dodger bowler hat), seemed to have been waiting for punk his whole life and when it finally exploded he was ready and willing to lend a managerial and media guru hand to acts like Ian Dury and the Blockheads and Johnny Thunders as well as to new labels like Stiff Records. Returning to Ireland in the 1980s, he resumed a career in radio and print journalism as he became a confidant, collaborator, advisor, and mythmaker to the likes of the Boomtown Rats (he claims to have “transformed Bob Geldof into a pop star”), U2 (providing wise counsel and backing vocals on their 1985 hit single “Pride”), The Pogues, Sinead O’Connor, My Bloody Valentine and countless others acts, often touring extensively with them as a resident photographer, writer, friend-along-for-the-ride, and opening act DJ. In the early 1990s, he toured the world with U2’s ultimately eerily prophetic multimedia Zoo TV enterprise and opened the band’s innovative stadium shows with eclectic DJ sets incorporating a plethora of songs and samples and even live feeds, performing his mixes from a car lowered into the audience (He was credited on the tour as “DJ, Guru and Viber”). He collected his journals and photos of the massive drama-filled and celebrity-heavy global tour into book form with U2 Faraway So Close, which was published by Virgin in 1994, and which chronicles BP’s own work as a mixologist and his interactions with the likes of O’Connor, Geldof, Keith Richards, Pearl Jam and Phil Spector as much as the doings of U2 (the book naturally features graphic design by Steve Averill). Throughout the 90s and early 2000s, he continued to work as a print journalist (reporting from the road with Van Morrison in 1996) and remained a popular and knowledgeable and very punky broadcaster in Ireland while also hosting his “Death Disco” DJ sessions, spinning records with special guests in clubs around New York, London, and Dublin (I was lucky enough to catch one of the Dublin sets in 2005 which featured Fallon, Shane MacGowan, and The Dubliners’ Ronnie Drew). More recently, King Boogaloo (as he is sometimes known) has established himself as a recording artist in his own right with his band BP Fallon and the Bandits. He currently lives in Austin, Texas where he continues to perform music and Beat Generation-inspired spoken word events with punk pedigree acts like Jack White, Alejandro Escovedo, Ghost Wolves, Richard Barone, and members of the Small Faces and Blondie.

While music has generally been foregrounded in discussions of the punk movement, punk rock was always part of wider cultural and artistic trends. Ireland’s Arts Act of 1973 was a huge step forward from the days of hard-line censorship, providing government funds for edgy creative projects that would previously have been banned, while the national broadcast network RTE began attempts to reach a more youthful audience through significant changes to its programming. The new counterculture associated with punk spawned a diverse wave of intellectuals, actors, writers, theater producers, and other artists who cast a subversive and revisionist eye on Irish culture and history. Stokes’ Hot Press magazine emerged in tandem with the 1977 punk explosion, and has since its inception focused on the postmodern convergence of music, art, pop culture, and politics. Experimental DIY artist Stano (formerly of the Threat) collaborated with many of the Irish punk scene’s musicians while incorporating his own pre-recorded musical compositions with found sound recordings into a multimedia presentation of bizarre slide and film projections that recalled expanded cinema happenings of New York’s Warholian Sixties. Despite signing with U2’s Mother label in the 1980s, Stano faded into relative obscurity, along with a whole catalogue of Irish acts that attained some renown in the punk era of the late 1970s and early 80s.

The Irish punk revolution also had deep ties to what would become the first wave of Irish cinema. The celebrated Irish film director Jim Sheridan, known for collaborations with Daniel Day-Lewis such as MY LEFT FOOT and IN THE NAME OF THE FATHER, also played a rather significant role in the Irish punk history of the late 1970s. While running his progressive Olympia Theater troupe, Sheridan opened an experimental art space called the Project Arts Centre in a former printing warehouse. “The Project was the only place in Dublin where things could happen at that time,” Sheridan remembers of the whitewashed derelict space, “because it was even hard to go to a gig…(At the Project), you’d smell someone smoking hash…and there’d be the Radiators from Space or U2. It was kind of wild.” The Project’s notorious “Dark Space” event in 1979 sought to combine punk rock with various other disciplines and strands of contemporary avant-garde expression through a marathon 26-hour festival. While British punk superstars PiL and Throbbing Gristle were apparently announced for the event but did not play, an audience of 800 was treated to a series of live performances by Irish bands, including the Modern Heirs, Rudi, DC Nien, the Virgin Prunes, and U2, providing a punk soundscape for the spectacles of various multimedia and performance artists. The happening effectively brought contemporary performance art practices to Dublin and established the new music as part of a broader artistic palette, inspiring Gavin Friday to incorporate more radical avant-garde theatrical elements into his Dadaist-influenced Virgin Prunes performances. Friday recalls that Sheridan’s unconventional venue “almost became our home,” with the future Irish film auteur encouraging the Prunes to “reinvent Irish music…with a rocket up its arse!”1 The Prunes’ subsequent appearance on a prime time television chat show “combined theatricality with stirring discordant music… (and) had an uncanny primal and angry quality rarely on view in Catholic Ireland,” remembers Darren McReesh. The Centre was the scene for a number of interdisciplinary avant-garde theatre pieces that often utilized the talents of experimental composers and musicians which fostered early dabblings in electronica and contributed to an emerging DIY tape-sharing culture among musicians and fans. Soon, even mainstream traditional Celtic acts like ethereal New Age mystics Clannad were experimenting with electronic sounds.

In the North, the Derry-based Field Day theatre group led by playwright Brian Friel, poet Seamus Heaney, fiction writer and soon-to-become filmmaker Neil Jordan, and actor/stage producer Stephen Rea embraced punk’s DIY ethos, traveling around the island and performing controversial and experimental theater pieces inspired by the New York underground but often tied to republican and nationalist politics. Beginning with his unhinged portrayal of a show-band musician’s descent into film noir hell in 1982’s ANGEL (closing out the AFS Irish series on December 19), Rea entered into a longtime cinematic partnership with Jordan, defining the director’s surreal and postmodern take on Irish themes and becoming the sullen punk face of the new wave of Irish cinema. On the stages of international theatre, Rea continues to frequently collaborate with his longtime American friend, the “cowboy punk” avant-garde dramatist and Hollywood actor Sam Shepard.2

Smaller towns in both the North and South also produced edgy and interesting punk-fueled talent with ties to broader cultural concussions. Dogmatic Choice, a Velvet Underground-influenced band from Bangor, County Down (home to legendary punk venues the Viking and the Trident) was managed early on by Colin Bateman, the future acclaimed novelist and screenwriter of DIVORCING JACK, the 1998 Belfast-set film starring David Thewlis that has become one of the primary texts of the new Irish cinema. More famously, Bateman is the creator of James Nesbitt’s titular Irish detective in the long-running hit TV show MURPHY’S LAW. Back in 1980, Bateman released Dogmatic Element’s first single on his own Cattle Company label. In the early 1980s, the Wexford-based outfit Major Thinkers emigrated to New York in the tradition of so many other Irish artists and musicians down the years, becoming a vital force in the Lower East Side art scene that was fusing No Wave post-punk noise and attitude with emerging multicultural trends like World Beat and the African American sounds of hip-hop and scratch.

With the popular success and major-label signing of Geldof’s Boomtown Rats, Anglo-American music industry heads looked to see what was going on in Ireland for the first time. Upon hitting the number one spot on the UK singles charts in 1979 with “I Don’t Like Mondays,” Geldof felt “a great sense of triumph. I felt very Irish! A person who’d never felt particularly Irish. And I was aware of its moment. This ‘Irish’ band. No other Irish band had ever got there. So it was a good moment.” The Rats and their ilk gradually moved away from the aggression of early punk into gentler manifestations of mainstream “New Wave” rock. U2’s third LP War, which featured the Troubles-themed hit single “Bloody Sunday,” was released in 1983 and quickly overshadowed the success of the Rats. The album reached number one on the UK album charts and, with a heavy assist from the hit New Wave-themed cable network MTV and Geldof’s Live Aid concert extravaganza, broke the band in America as well.

What most distinguishes the creative explosion of Ireland’s punk and new wave scene from that of similar ones elsewhere is that it proved to be truly revolutionary, leading to a greening (pun intended) of local culture like that of America’s hippies in the 1960s. “I didn’t know at the time that 50% of the population was my age in effect,” Geldof recalls, “and that the world was gonna crumble really fast. I just didn’t expect it to fall so fast.” Beyond the local, the Irish punk and new wave artists rocked the wider world in a dramatic fashion that socially conscious British groups like the Clash only dreamed of. Geldof soon used his newfound celebrity status to move rock music into the realm of global charity with his 1985 Live Aid brainchild, an unprecedented undertaking that rallied the MTV New Wave pantheon and a vast network of other high-profile celebrities into a series of international concerts and telecasts staged for the effort of famine relief in Ethiopia. Geldof and company, including U2, succeeded in raising around 200 million dollars for the charity, marking Geldof and Bono as secular celebrity saints in lineage to the long tradition of far-flung charitable works by Irish Catholic missionary monks.

Today, Geldof is likely remembered by film buffs and rock fans alike solely for his intensely punkish performance in Alan Parker’s PINK FLOYD THE WALL (1982), arguably the most artistically accomplished of the works to come out of the “cult film” and “midnight movie” phenomenon of the 1970s and 80s. U2 of course continued its meteoric rise to become one of the most universally revered bands in the world, while the Irish musical revolution continued with the international successes of simultaneously punk-tinged and tradition-steeped acts like Sinéad O’Connor, the Cranberries, and My Bloody Valentine, who became staples of the emerging alternative and indie rock movements. O’Connor’s punk agitprop theater has included outraging Irish Catholics throughout the world when she ripped up a picture of the Pope on a live television broadcast, although she has since returned to both the Catholic Church and traditional Irish music.3

The international popularity of what began as the Irish punk movement was far-reaching on a number of levels, not least in bringing Irish culture in general to international prominence and, alongside directors like Jordan and Sheridan, creating a cultural export phenomenon that created an Irish vogue throughout the west. It was suddenly very “hip” to be Irish, and Irish-themed culture seemed to run rampant in the 1990s in tandem with the success story of the Celtic Tiger economy (Riverdance, anyone?). In the US, Hollywood rushed out a slew of Irish-themed films as the works of Sheridan and Jordan received Oscar nods, resulting in many of the new Irish cinema’s actors- Gabriel Byrne, Daniel Day-Lewis, Liam Neeson, Stephen Rea- quickly becoming Hollywood A-listers. Irish music festivals sprang up across the land, and the Irish pub, formerly a slice of authentic immigrant ethnicity in the major cities, now became a staple of US suburbs. Inspired by the culture-jamming Pogues, Celtic punk bands like the Dropkick Murphys, Flogging Molly, and the Tossers became vital forces in the second generation US punk scene, forging a permanent and perhaps not so inappropriate connection between Irish folk tradition and the postmodern punk subculture. And of course, the Irish punks must be given credit for supplying seasonal revelers with the only two classic Christmas pop hits of the latter Twentieth Century: The Pogues’ incredible “A Fairytale of New York” and, for better or worse, Geldof’s Live Aid-affiliated Irish hymn, “Do They Know it’s Christmas (Feed the World).”

Tonight’s compelling double feature offers both a fictionalized version of Ireland’s punk history followed by a personal autobiographical account of the same. In Johnny Gogan’s THE LAST BUS HOME, two young punk rockers find themselves united by the music of the Undertones and by seemingly being the only two people in Dublin not greeting the Pope on the day of his historic visit in 1979. “They are the island’s inner exiles,” writes Lance Pettit in Screening Ireland. “Finding no connection with the mass observation,” they are instead symbols of “the division that opened up at the end of the 1970s between tradition and iconoclasm, between the Pope and punk.” The two kids forge an alliance, fall in love, start a band and weather the ups and down of rock and roll well into the transformed Irish and pop musical cultures of the1990s. Taking the creation myths of Irish punk pioneers like the Undertones, Boomtown Rats, Stiff Little Fingers, and U2 as its impetus, THE LAST BUS HOME examines the power and glory of the early Irish punk scene, its commercial commodification, and its ultimate transformation and inherent unsustainability. The film is also a testament to the close ties between Irish punk music and the country’s indigenous folk traditions and history; as well as the island’s ongoing struggle for Irish nationalism and identity. As far as the music, politics, and image of the film’s fictional band, the filmmakers clearly look to the subversive Celtic rebel punk of the Pogues for inspiration. The group’s very name the Dead Patriots is loaded with allusions to Ireland’s various historic nationalist movements and the Troubles, while also alluding to the San Francisco-based punk band the Dead Kennedys, adding another level of Irish subtext. The Irish tri-color is prominently displayed in the group’s promotional materials; and as the Patriots belt out traditional Irish songs to a punk beat, the group’s audience, like that of the Pogues, is left to wonder whether the band is affiliated with the Republican agenda or if it’s all simply a snotty, irreverent joke.

LAST BUS embraces the new Irish cinema’s agenda of challenging traditional taboos, from the self-empowerment and refusal to conform to established gender roles of the film’s central female character Reena (Annie Ryan, channeling punk feminist Sinéad O’Connor) to the explicit and tender homosexuality of the band’s drummer Petie (John Cronin). The skinhead gangs at the fringe of the punk scene, simultaneously a part of punk culture and its hardcore antagonists, provide an interesting and appropriate symbol of the Irish right-wing establishment’s prevalent racism, sexism, and homophobia (homosexuality was a criminal offense in Ireland until the 1990s), and are representative of gangs like the ironically-named Black Catholics, a notorious gaggle of skinheads known for frequently bringing violence and causing trouble at Dublin punk gigs.

As always in Irish cinema, visual metaphors abound. The dismal and gray wasteland of abandoned Dublin that threatens to overtake Reena as she waits in vain for a bus that will not come suggests both the cultural void of 1970s Irish life and the character’s own psychic state of dislocation and boredom, a mingling of the despair of the present and a hopefulness for the future. Gogan’s ambitious film perhaps takes on more issues than it can adequately address, including class conflicts, the need for alternative “tribal” family units, the generation war, cultural transformation and overhaul, and the nature of consumerism. But isn’t that what punk did as well? At its heart, LAST BUS is really about the Ireland of its time of production (which is also the temporal setting of the film’s final chapter) and the glorious punk roots of that cultural shift located back in the late 1970s and 80s. “Johnny Gogan’s film,” Martin McLoone writes, “is not only one of the most astute comments yet on the smugness of the ‘Celtic Tiger’ society; it is also one of the first revisionist films about the punk era.” Rather than the symbolic music cult heralding the death of the peace and love generation and the birth of apocalyptic and postmodern culture that punk represented in the US and Britain, in THE LAST BUS HOME the hope, promise and empowerment at the heart of the early Irish punk scene is in sharp focus, as is the unavoidable maturation and cynicism that ultimately destroys youth movements like the Hippies and Punks but allows them to pass the torch to the next generation.

Two other films of the contemporary Irish cinema beg comparison with THE LAST BUS HOME. Alan Parker’s lighthearted THE COMMITMENTS traces the rise and fall of a fictional Dublin soul band and was a huge international arthouse hit in 1991, although Pettit insists that it is “shallow and exploitative” next to Gogan’s largely unseen punk history film. More recently, Nick Hamm’s KILLING BONO (2011) tells the mostly true story of the collaborators and fellow travelers left behind in the Irish punk revolution and U2’s ascension to worldwide glory.

American TV audiences will likely recognize THE LAST BUS HOME’s male lead David F. O’Byrne as “the Irish guy” from television series like OZ and LAW & ORDER and from his recurring role in BROTHERHOOD, Showtime’s brilliant Irish-American gangster drama. He also recently received an Emmy nomination for his work in Todd Haynes’ reimagining of MILDRED PIERCE for HBO in 2011. On the big screen, he portrayed Clint Eastwood’s Irish priest in the Oscar-winning MILLION DOLLAR BABY (2004) and has appeared in high-profile American films such as THE NEW WORLD (2005), BEFORE THE DEVIL KNOWS YOUR DEAD (2007), BUG (2007), and BROOKLYN’S FINEST (2010). In addition to LAST BUS, O’Byrne has appeared in a number of the late classics of the Irish new wave cinema, including DISCO PIGS (2001) and INTERMISSION (2003); and he and LAST BUS director Johnny Gogan also collaborated on 2001’s THE MAPMAKER, with the actor portraying a civil servant surveyor mapping the Irish border regions still haunted by the ghosts and intolerance of the Troubles. O’Byrne’s sad eyes and dour, punkish, and very Irish persona convey a violent intensity roiling just under the surface, and his screen image has much in common with that of Irish screen legend Stephen Rea.

Director Johnny Gogan was born in England but moved to Ireland as a child, establishing for himself early on the prerequisite of displacement and cultural schizophrenia seemingly required by the Irish cinema. In 1987, he launched the magazine Film Base News (later Film Ireland), which over the years has acted as a sort Irish rendition of Jonas Mekas’ Film Culture mag of the New York Sixties, similarly exposing and legitimizing the young underground and low-budget filmmakers coming up throughout the island. Much like Mekas’ Film-Makers’ Co-Op, Film Base also acted as an organization that “hired out equipment, collated information resources, (and) provided a focus for ‘wandering’ film-makers…(offering) support and advice” as well as screenings of film and video works by emerging local artists. Gogan’s fourth feature BLACK ICE, another Irish teen rebel tale centered around illegal road racing, was released on the island in 2013 but, like most indigenous Irish film, will not likely be seen in any format stateside.

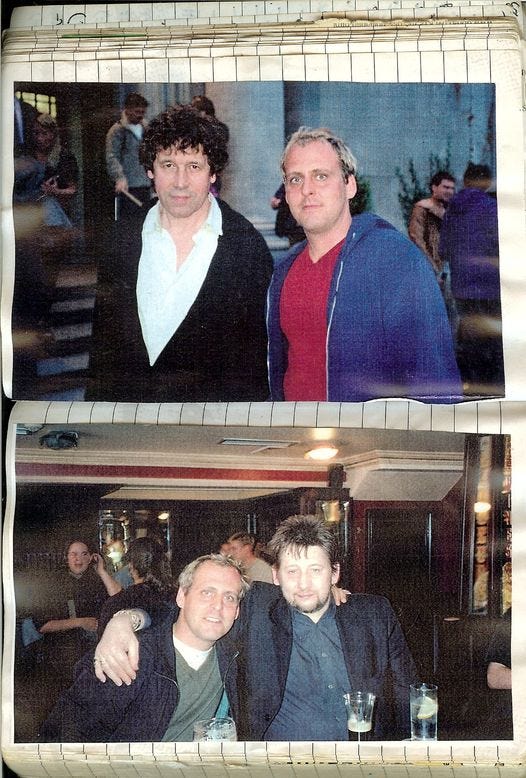

The author in Dublin with Stephen Rea and Shane MacGowan, 2001

Sarah Share’s brilliant documentary on Shane MacGowan IF I SHOULD FALL FROM GRACE can be enjoyed as both a crowd-pleasing, foot-stomping rock-doc as well as a dense distillation of the themes and preoccupations that generally pervade the contemporary Irish cinema: The diaspora and cultural displacement; anti-Irish racism; “the Troubles;” Irish Nationalism; alcoholism; the Bardic legacy of Irish poetry, storytelling, music and folk culture; “Paddywhackery;” Catholicism; family; community; and the ultimate Faustian price paid for personal integrity and maintaining “Irishness.”

While Gavin Friday viewed Radiators from Space frontman and future Pogue Philip Chevron as “Johnny Rotten meets Brenden Behan” in the 1970s, it was in fact MacGowan who took the two as his primary influences. Behan, a former IRA man and ex-con, was the revered Irish raconteur and author of a large body of stories, memoirs, plays, and songs that did much to define contemporary Irish identity and culture after World War II. Behan’s career was cut short in 1964 (the same year the Rolling Stones first toured Ireland) due his premature death at age 41, the result of advanced alcoholism. MacGowan seems to channel both the artistic genius and nationalist sentiment of Behan’s legacy, as well as the dark side of his very Irish dissipation. Like so many Irish artists, both Behan’s and MacGowan’s creative outputs and lifestyles have been tragically defined by their cooption and personal ownership of too many well-worn and ultimately destructive Irish stereotypes, a phenomenon known variously as “Stage Irishness” or “Paddywhackery.”

Never forgetting that his family’s land in Ireland is his true spiritual home, young Shane found himself uprooted at an early age when his parents moved to London for work. Chevron ruminates in the film that “the Pogues could never have been an Irish band indigenously…It’s like there’s two Irelands; there’s the people who live on the island and the people who went away and are first or second generation. And very often that gives a very different point of view on the culture, of what it means to be Irish.”

Suffering from displacement and the anti-Irish sentiment of his new environment, MacGowan found acceptance and community in London’s emerging punk subculture. After forming punk-soul outfit the Nips, he soon realized that playing traditional Irish Republican fight songs to a frenetic rock beat was perhaps the most punk rock thing one could do amid the climate of England’s war with the IRA in the early 1980s. Still making music today and occasionally reuniting the Pogues, MacGowan is at once a poetic storyteller in the ancient Irish folkways tradition, a mesmerizing performer, a godfather of British punk, and a contemporary songwriting genius in the dark bardic lineage of Nick Cave, Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan, Will Oldham, Lou Reed, and Tom Waits. “There’s a great visual sense to him,” filmmaker Jim Sheridan has said of MacGowan’s songcraft. “He’s weird in that way, in that you can almost see the songs.” Featuring insightful commentary from his closest friends, family members and collaborators, and at once heart-breaking and inspiring, Share’s film suggests that despite the hard road taken, MacGowan has yet to fall from grace with God. An intense portrait of a fierce, drunken and battered Irish Republican fighter trapped in the soul of a hopeless tragic romantic poet, IF I SHOULD FALL is testament that popular music will not see the likes of Shane MacGowan again. As the recent passing of the great punk icon Lou Reed should remind devotees of singer-songwriter melancholia, it is a fitting time to revel in MacGowan’s exquisite genius and to celebrate one of rock’s true innovative visionaries while he yet lives.

Sources:

Adam, R. (2017). Belfast Punk: Warzone Centre 1997-2003. Bologna, Italy: Damiani.

Coogan, T.P. (1993). Eamon De Valera: The Man Who Was Ireland. New York: Barnes & Noble.

Deer, P. (2013). “The Cassette Played Poptones”: Punk’s Pop Embrace of the City in Ruins. Social Text, 116, 147-58.

Fallon, B.P (1994). U2: Faraway So Close. London, UK: Virgin Books.

Gibbons, L. (1996). Critical Conditions: Field Day Essays: Transformations in Irish Culture. Cork, Ireland: Cork University Press.

Gray, M. (1995). Last Gang in Town: The Story and Myth of The Clash. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Heffernan, D. (Producer/Director). (2000). From a Whisper to a Scream: The Living History of Irish Music [Motion Picture]. Ireland: Radio Telefis Eirann/ Investment Incentives for the Irish Film Industry.

Lydon, J. (1994). Rotten: No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs. New York: Picador.

MacGowan S. & Clarke, V.C. (2001). A Drink with Shane MacGowan. New York: Grove Press.

McLoone, M. (2000). Irish Film: The Emergence of a Contemporary Cinema. London: British Film Institute.

McReesh, D. (2012). Liner notes. On Strange Passion: Explorations in Irish Post Punk, DIY and Electronic Music 1980-83 [CD]. London: Finders Keepers Records

Pettitt, L. (2000). Screening Ireland: Film and Television Representation. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Savage, J. (1992). England’s Dreaming: Anarchy, Sex Pistols, Punk Rock, and Beyond. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

http://diyirishhardcorepunkarchive.blogspot.com

http://www.spitrecords.co.uk/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Good_Vibrations_%28record_label%29

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Harp_Bar

Former Virgin Prune Gavin Friday, along with his creative partner Maurice Seezer, would go on to provide the musical scores for Jim Sheridan’s films The Boxer, In America, and Get Rich or Die Tryin’ (also working with Quincy Jones on the latter). Before this, Gavin had collaborated with both Bono and Sinead O’Connor on songs for the director’s In the Name of the Father (Interestingly, the Pogues had previously recorded a song about that film’s subject the Guildford 4, who were wrongfully accused of an IRA bombing in London). Furthermore, Friday had a small acting role alongside Cillian Murphy in the film Disco Pigs, directed by Sheridan’s daughter Kristen, and had a more substantial role a few years later in Neil Jordan’s punky transgender film Breakfast on Pluto, again cast alongside Murphy. Since leaving the Virgin Prunes in 1986, Friday has emerged in his solo work as as something akin to a Dublin hybrid of his hero David Bowie and the experimental cabaret of Tom Waits filtered through U2’s 90s electropop period. Clearly the Friday/U2 influence runs both ways. In addition to his many collaborations with the groundbreaking American producer Hal Willner on various recordings and epic live performances, Friday also continues to be the creative director behind U2’s ever-innovative multimedia concert extravaganzas, with Bono even channeling the performance art and persona of his old pal on the Zoo TV tour.

Sam Shepard passed away in 2017, shortly after the AFS Irish series.

O’Connor became an ordained priest in a Catholic splinter sect before renouncing Christianity for Islam in 2018.

Amazing exploration of Irish punk rock and related movements. Really interesting stuff. And thank you for the links to the videos, especially "Troy." Sinead O'Connor was severely underrated and misunderstood. We lost a great one with her untimely death.

No surprise, ENJOYABLE!