Happy 125th birthday to the late great Charles Laughton, one of the most fascinating, uniquely talented and weirdly charismatic thespians in the history of stage and screen. What follows is another mummified remnant from my academic vault of horror, originally written as a term paper for Harry Benshoff’s brilliant “Gender and Sexuality in the Horror Film” class at the University of North Texas, 2001 and I later used it as supplemental reading in my own film courses over the years. Thank you as always for reading, and thank you Harry for your inspiring and very cool film studies courses at UNT. This one is dedicated to my dear mother, who first introduced me to the brilliance of Charles Laughton and so many other dark treasures of the Classical Hollywood Cinema.

Charles Laughton: Hollywood Horror's Queer Outsider

"...Philosophy of life: a little theory that my father handed on to me...my father used constantly to wonder whether it would be an entertaining experiment to cut my heart out. I think he eventually decided against it, however, on the grounds that it would mean the end of other and still more entertaining experiments... he stripped me and beat me till I bled. He wanted, he said for my own good, to acquaint me with the heart, the innermost heart of life; and to understand life, one must learn to suffer pain. Then if one could suffer pain enough, one could be as God. I went to Westminster School and they all mocked me- my hair, my body, my difference- yes, my difference. I was different from them all, I was different from my father, different from all the world, and I was glad that I was different. I hugged my difference. Different... different...different." - Crispin in A Man with Red Hair by Hugh Walpole

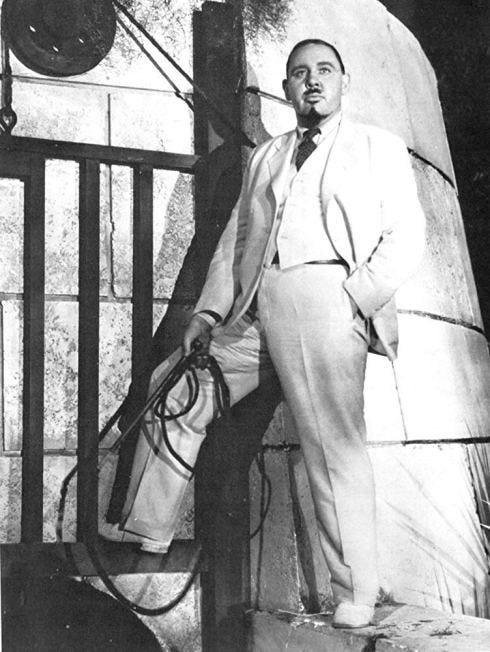

Although the above soliloquy was not penned by or specifically for Charles Laughton, it does mark an early high point in his career of portraying "low" and debased characters. Among his earliest professional stage performances, Crispin is his first "monster-villain" and hints at many future characterizations as well as themes that would continue to run throughout a distinguished and often disturbing career on stage and screen. Ever the "actor as auteur", Laughton’s most powerful portrayals seem always rooted in depravity, horror, and the guilt and perverse pleasure of some unspeakable dark sexuality. The virtue, and curse, of his strange physicality enabled him to inhabit such roles and "become" the character to an extent of which other leading men and character actors of his day were incapable. Indeed, it is the harsh juxtaposition of both his style and physical form against that of his fellow players that lend his performances their power. His very presence suggests something unnatural and unsettling, something authentically out of step and alien. The horrifying indecency of his Crispin in the Walpole play was so intense as to be threatened with action by the London Public Morality Council shortly after its premiere in 1928. Laughton would later state in reference to his peculiar ability to disturb an audience, "They can’t censor the glint in the eye."

Simon Callow’s thorough and insightful study of the actor reveals a vivid portrait of the reclusive Queer Outsider.1 One of three sons born to middle-class Catholic hoteliers in provincial England near the turn of the last century, Charles Laughton seems to have been destined for difference from the beginning. Raised more or less by maids and hotel clerks, the Laughton sons hardly knew their parents, and Charles would grow to resent both their absence from him as well as their Bourgeois airs. The Laughton family were outcasts of sorts; the community viewed them as pretentious snobs. One boyhood acquaintance of Laughton describes him as a tubby bookworm, "the kind of boy one longed to take a good kick at". As a youth, Charles developed a lifelong habit of poor hygiene and increasingly affected a slovenly, disheveled appearance and an interest in radical politics in order to distance himself from his roots. He longed to live among the "normal" working class. His Catholic schooling, compounded with the painful growing awareness of his homosexual orientation, instilled lifelong feelings of guilt and shame in him, an epic malaise of "not being right in the world, of not deserving of what the world had to offer."

Following a tour of duty in World War I, he returned to the family business, deeply morose from his experiences. Finally breaking with his parents, Charles entered the fringes of the London theater orbit, possessed of "the face of someone who simply shouldn’t be an actor at all." Far from sociable, his time at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art was spent in quiet meditative study outside of rehearsal and performance, aloof and making up for lost time. He soon exploded onto the London stage, "summoning repressed and shapeless desires out of the shadows".

As at RADA, he distanced himself from fellow players even when they were sharing the stage together. The theater provided him a touchstone with the human race of which he had an almost pathological aversion. "His work as an actor gained him a kind of co-opted membership of it as a tragic fool, a court jester whose maimed body served as a means both of facing misfortune and laughing at it." Tormented by a masochistic loathing of his unconventional physicality, he was doomed to arrive at his brilliant characterizations through long and torturous processes of morbid introspection. Unkempt and unpleasant, "his reputation was increasingly that of a man apart, an eccentric". Old before his time, he was a lonely outsider everywhere but the stage, where he immersed himself in bizarre self-portraits, confessing to a dark inner nature that rebelled against the repressive social mores and oppressive politics of his time and often manifested itself in cruelty.

He married the actress Elsa Lanchester, a lasting but seemingly tragic union that exacerbated his Catholic guilt and fueled his self-perceived sinful nature, and the couple set out to take Hollywood in the early 1930s. Mr. and Mrs. Laughton, brought together by loneliness and mutually odd natures, became a famous eccentric couple in Hollywood and were the source of a cover story by one tabloid entitled "The Strange Pair", in which they staged a lavish production to assert their "normalcy". A 1935 article in Time contrasted Charles’ "plump effeminacy" with Elsa’s "mannish" dress. Strangely if suitably enough, Laughton’s celebrity was likened by one of his most adoring critics, James Agate, to that of Garbo and Dietrich, altogether omitting any comparison to a male actor.

Fiercely anti-capitalistic, Laughton was enamored of the populist nature of cinema; "art for the masses" as opposed to the highbrow pretensions of live theater. Nevertheless, His work in Hollywood was marked by the same ill at ease shyness and refusal to engage in small talk that he had established in the London theater as well as a continuing reputation as a difficult actor. "His art of acting, which consisted of driving himself relentlessly to reveal unpalatable aspects of his personality, was not calculated to endear him to anyone." Nevertheless, he was among the most popular and well respected actors of the 1930s while specializing in "exploring the disorders of the human spirit".

The personal expense of these portrayals was surely harrowing. Laughton was all too aware of the degree to which he was at odds with both society and its notion of a leading man. What leading man would reveal his dark ugly secrets as Laughton dared--A very Catholic shame of homosexuality and self-hatred; a contempt for the status quo; an inherent feeling of alienation and difference; a sadomasochistic cruelty; an unbridled sexuality. Laughton’s gift to the arts was the uncanny ability to allow his dark side to envelop him completely for all the world to see. His tormented sense of difference was given free reign in the public imagination; his suffering was made flesh.

Such intense feelings of alienation and otherness as suffered by the artist in particular are the subject of Colin Wilson’s scholarly work of modern philosophy, The Outsider. Wilson was at the front of the Angry Young Men literary movement of the 1950s, a British answer to the Beat Generation. While the work arguably suffers from a degree of over-academic, masturbatory pretentiousness, it without question sheds light on what the author perceives as the central problem, or curse, of genius. Ultimately indefinable, Wilson’s idea of the Outsider’s plight centers around a fundamental depression, or existential angst, which stems from a sense of self-perceived otherness and an inability to fit into the world at large. This leads to a crisis of the spirit that drives the gifted one to either creation or self-destruction. A troubled and guilty soul; the perception of a world that is cruel, foreign and spoiled; a deep sense of futility and displacement; the strength to create in such a void; this is the haunted playground of the Outsider. Wilson summarizes the challenge thus:

The Outsider wants to cease to be an Outsider. He wants to be integrated as a human being, achieving a fusion between mind and heart. He seeks vivid sense perception. He wants to understand the soul and its workings. He wants to get beyond the trivial. He wants to express himself so he can better understand himself. He sees a way out via intensity, extremes of experience.

Through an examination of the lives, works and sufferings of a diverse representation of “geniuses”- Nietzsche, T.E. Lawrence, Van Gogh, Nijinsky, Blake and Hemingway, to name but a few-- Wilson analyzes and elucidates the nature of the tortured and alienated artist and posits ways to deal with the peculiar problem of the Outsider. Laughton seems a logical addition to the distinguished canon Wilson has compiled, both in the genius of his artistic contribution (particularly in light of Wilson’s odd omission of an actor in his study), and as an outsider not only by Wilson’s psychological and spiritual standards, but physically, overweight and bizarre in appearance, and sexually, gay, as well. It is in these attributes that Laughton becomes the Queer Outsider, a subject generally shied away from in Wilson’s work, and strangely so, due to both the loosening of sexual roles within artistic circles and the evidence pointing to the conflicted feelings that homosexuals and all those existing outside the standardized gender roles proscribed by the dominant heterosexual hegemony have historically had about themselves. Like any subculture, the sexually ambiguous are outsiders (indeed outlaws) by their very nature, art and all else aside.

The cinema of horror has from its inception been thematically centered on a binary of the "Other", represented as monstrous, in contrast with the "Normals", the bourgeois minions of the prevailing ideology. Certainly Laughton would have had a great interest in the coded texts of monstrous otherness, threatening sexuality, and repression within the genre, as well as the anti-establishment sentiment the themes often inherently evoked. Had he not been drawn to the genre, he would surely have been heavily recruited for roles within it due to his disturbing presence, not to mention his perverse acting style and raw talent. Laughton was in some ways tied to horror simply by his reputation as a highly unorthodox acting powerhouse. The blatant queer undertones running amok throughout the classical Universal horror films and their imitators would not have been lost on such an intellectual. His horror roles, and other performances of this period which are often indistinguishable from horror, constitute a curious "coming-out" for an actor who never fit in, despite critical notice and public acclaim: Too unkempt for the classical sect, too unsightly for the younger cutting edge dramatists, and overweight and effeminate as well. While nearly unanimous in their praise, most contemporary reviews of any Laughton performance allude to either his physical ugliness or the grotesque rendering of his character, and generally a hybrid of both. Callow provides a range of these "critical" assessments from throughout his career, and it is worth noting a few before proceeding:

His entrance is like the first whiff of poison gas...a thing so evil and malignant...by what witchcraft Mr. Laughton produces the effect, I don’t know...A danse macabre rendered by a human invertebrate, whose sagging flesh would somehow shape itself into all manner of harsh angles and gibbet-like postures... A very gargoyle of obscene desires...

Mr. Laughton’s essential genius is concerned with the portrayal of the sinister, all the more horrific because of the fleshly suggestion... Laughton arrives at his characterisations panting, having picked up a hundred oddments on the way...Here was utter abandonment to funk and terror...Laughton is himself one of the oddities of human nature: that pale, puffy face, curious manner of walking, his shoulders hunched up, one a little higher than the other, that jerky step...

Laughton’s macabre queerness seemed to be a benchmark of sorts, as even accounts of other strange actors of the time evoke his name. Time Magazine published an article on Peter Lorre in 1935 asserting that he "uses the technique popularized by Charles Laughton of suggesting the most unspeakable obsession by the roll of a protuberant eyeball (and) an almost feminine mildness of tone."

While the critics were virtually unanimous in their praise of his twisted creations, they were seemingly unable to separate his acting prowess from the sideshow novelty of his appearance and demeanor. While he was always one to rely on his odd physiognomy to convey the depraved and grotesque, the notices would surely have seemed the best and the worst to Laughton. On one level he was widely regarded as the most original and talented actor of his day, but this had been accomplished at the expense of a sense of dignity regarding his physical shortcomings and strange persona. As a lover of beauty-- not to mention as a homosexual with the complex standards of desirability which it imposed upon him-- Laughton’s "freakishness", while hardly unappealing to audiences, troubled him until the end of his life. His unique face and body were at once the key to a very physical acting style which garnered much acclaim, and a depressing reminder of how different he truly was. Callow elaborates on Laughton’s otherworldly physicality and presence throughout his biography of the actor: The "strange sensuality, perhaps even sexuality" he brings to performances which contain "real sexual aggression", "poetic menace", and are "both sexy and alarming". "Carnal with a grossness that is repellent" and "cruel with a hideousness that is sickening". "There is something weird about his appearance, inhuman, bat-like...a not dissimilar quality to that of Max Schreck in Murnau’s Nosferatu, a self-consuming intensity that is heart-stopping".

He is an enigma, unable or unwilling to suppress both a perverse sensuality and a sociopolitical critique within his roles. Queerly, he is widely loved by spectators and critics alike.

PORTERHOUSE

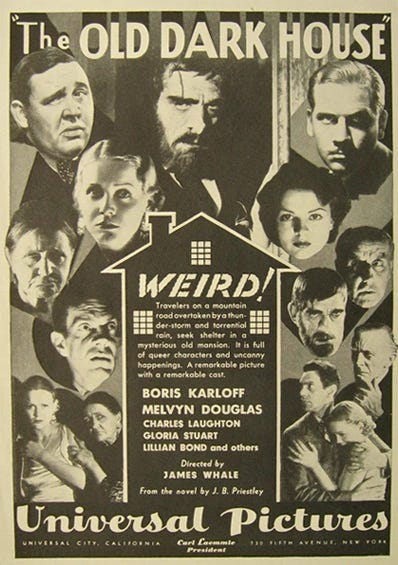

Released in 1932, James Whale’s The Old Dark House was among the original cycle of Universal horror films that followed the success of the openly gay director’s Frankenstein. Based on the story "Benighted" by J.B. Priestley, it is a bizarre comic portrait of queer sexuality featuring, in addition to Laughton in one of his first Hollywood roles, the queeny eccentricity of Ernest Thesiger (as Horace Femm, no less). To elaborate on the many fine perverse performances in the film would perhaps eclipse Laughton’s own subtle and complex contribution. In a queer house such as this, with inhabitants like Thesiger, Boris Karloff, Brember Wills, Elspeth "John" Dudgeon, and Eva Moore stretching the strange script to a level of surreal proto-camp and the bitchy biting black humor of Whale overseeing all, it may not surprise that Laughton, arguably the most famous queerly-tinged actor of his day, portrays not a member of the ghoulish Femm clan, but instead the most complex and developed character of the five "normals." Callow has remarked that within perhaps the quirkiest ensemble cast ever assembled, the fact that Laughton makes an impression at all in such a role is no mean feat. The residents of the house appear to be a family of insane sexual degenerates who reluctantly provide five stranded motorists with a harrowing and humorous night’s shelter from a rainstorm. Among other indulgences, incest, pyromania, murder, child abuse, homosexuality, alcoholism, bondage, rape, and general depravity are all implied amongst the family members with a blatancy that would cease to exist with the advent of the Production Code less than two years later.

Following the arrival of Penderel and his two friends, a bickering sexually tense couple, Laughton's Sir William Porterhouse, their fellow stranded guest in the weird old dark house, immediately sets himself apart from his fellow guests. In the polite and coded vernacular of the 1930s, a man like Porterhouse would have been referred to as a “gentleman dandy” or perhaps a “voluptuary.” He certainly lacks the conventional gendered beauty and charisma of Melvyn Douglas’ Penderel and the other stranded guests, and while the other decidedly masculine and heroic male leads reveal a genteel sophistication within their standard restrained "English Gentleman" style delivery, Porterhouse enters with loud, obnoxious donkey bray guffaws and a booming Welsh brogue, a sense of forced and false masculinity. It is immediately apparent that whatever relationship exists between Porterhouse and his lady friend, it is not remotely sexual; there is no hint of intimacy or comfort between them. After an elaborate dinner with the hosts and their guests, Porterhouse hints at possible reasons why when he informs the others that while they have talked for over two hours, "What do we know about each other? Not a thing." In response to Horace Femm’s delirious mutterings as to why anyone would live in such a house if he didn’t have to, Sir William responds rather flamboyantly, "There’s no accounting for taste you know. (Guffaw!)"

Porterhouse almost immediately reveals himself as a closeted homosexual hiding behind the veil of a confident hetero patriarchal capitalist. When he feels his true nature about to be exposed, he turns a discussion of financial ambition into a heated defense of his own manliness. "A fine speech", he informs Penderel in a sweaty, paranoid state, "but I know you’re only trying to get at me!" He goes on to add that while Penderel may envy him- due to his wealth-, he doesn’t admire him- presumably due to his obvious homosexuality. "Sometimes I don’t admire myself", he sadly concludes, an example of Laughton’s uncanny manifestations of very real queer outsider shame. Capitalism is an interesting ironic metaphor for hidden homosexuality on many levels, and Laughton’s fiercely heartfelt anti-establishment convictions add yet another layer of irony to the masquerade, even as Penderel reveals himself to be something of a Marxist.

Porterhouse goes on to tell the story of his dear departed wife; however, like his grandstanding on financial success, it doesn’t ring true despite a desperation he exudes that is very real. It becomes obvious rather quickly that if in fact she did exist, she has at this point become an absent "beard" to account for his lack of heterosexual companionship. Assuming the tale of the deceased spouse is true, theirs would certainly have been similar to the unconventional matrimony of Laughton and Lanchester. On a defensive tirade due to the perceived scrutiny of the four "straights", Porterhouse insists that his wife was driven to her death (by suicide it is implied) due to a shame at not being able to live up to his peculiar high society aspirations, yet it is the shame and humiliation of his own homosexual guilt that seems to pour forth. Ironically, her death centers around the plain dress she wore to a party, stressing again the idea of appearances, as well as her substitution for Sir William’s homosexuality. His drive for moneymaking, he tells his captive audience, stems from his desire to "smash" the society that would not give his possibly fictional wife--and his very real queer self-- "a kind word". Again, it seems the outsider Porterhouse is covertly exposing his own experience as a closeted gay man within patriarchal England, while also mirroring Laughton’s own plight not only there, but also in Hollywood and the world at large. "You may not believe it, but that’s what killed her!"--not his queer appetites, he desperately seeks to make clear. "I may be this and I may be that. But you don’t catch me pretending to be what I’m not!"2

It is not inconceivable that Whale and Laughton were indeed indulging in dark self-parody here, as Lanchester, who would soon take the title role in Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein, was in fact dealt a tremendous blow from which she never fully recovered upon discovering Charles’ sexual orientation, and theirs remained a troubled, asexual it would appear, relationship to the end. Laughton’s own torment upon her discovery reduced him, in her words, to a "quivering, blubbering wretch" arousing "mingled feelings of disgust and pity". Regardless, Porterhouse’s closeted sexuality and sense of guilt provide obvious and valid parallels to the actor himself, and this could not have been lost on the two gay men.3

As their conversation continues, Sir William’s chorus girl escort confides that if she were herself more successful, she wouldn’t be weekending with him, making even clearer the fact that there can be no passion between them; she is simply another beard, a front of respectability, and she makes no effort to disguise the physical revulsion Porterhouse inspires in her. This female mocking of his "ugliness and undesirability" would prove "almost de rigueur" in Laughton’s subsequent work. Affirming that she also can’t be what she is not, she concludes that Porterhouse is "nice enough" and that they get along fine, "but...". She stops there, just short of stating that any possibility of their relationship evolving sexually or into marriage is an absurd notion indeed. In a private conversation with Penderel later in the evening, she reveals that while she is Porterhouse’s paid escort, he doesn’t "expect anything. I suppose that’s what he wants me for... well, company." Penderel appears to buy the story, dead wife and all, but both he and the girl seem to be enacting a generous politeness that belies their mutual knowledge of the obvious difference Porterhouse represents. Following an implied sexual interlude in the car, Penderel and the girl return to the house where Porterhouse briefly and unconvincingly plays the part of the jilted lover. Indeed, the cuckold seems plainly relieved to have the woman off his hands; yet another absent notch of credibility for his contrived heterosexual identity. Penderel perceives this, as he has grasped Porterhouse’s secret from the beginning, and he continues to demonstrate an open-minded acceptance of his fellow refugee’s queerness:

Penderel: Will you come to the wedding?

Porterhouse: I think yer off yer ‘ead!

Penderel (insinuatingly): Do you...?

Porterhouse (smiling knowingly): Nooo...

Finally convinced that the sympathetic "homofriendly" Penderel poses no threat to him, Sir William bursts out in relieved laughter, embraces him and agrees to attend their wedding.

If it appears that much is being made of Douglas’ rather bland leading man portrayal at the expense of Laughton’s commanding supporting role, this is for good reason. The character of Porterhouse is manifested solely through his conversations with Penderel. These two characters exhibit the only extensive rapport within the circle of normals apart from the burgeoning romance between Penderel and the chorus girl. Despite well established relationships-- a married couple and their mutual old friend, a sugardaddy and his mistress-- it is difficult to recall any substantial dialogue between the intimately bonded characters; it is only these strangers that attract and interest one another, losing their inhibitions in the queer environment of the old dark house. Furthermore, Penderel is a curious doppelganger to Porterhouse. While Sir William desperately tries to hide his homosexual shame beneath the guise of a typical money-grubbing business tycoon, Penderel has revealed himself as a non-materialistic free-thinking bohemian vagabond despite the appearance of a white patriarchal capitalist poster boy. Indeed, until Porterhouse’s grand entrance, Penderel has filled Laughton’s sexually ambiguous role amongst the normals. They are both outsiders at war with the same powers of oppression. Each dons a similar mask, however only Penderel is comfortable with his subversive nature and has no issue revealing it to society at large. The world-weary Porterhouse seems revitalized by the validation a sympathetic Penderel bestows upon him. It is Penderel’s acceptance of Sir William’s covert sexual orientation that fuels the development of Laughton’s characterization, and it marks one of old Hollywood’s rare representations of a mutually respectful straight man-gay man friendship.

When first introduced, the Porterhouse character serves as an ambiguous middle ground between the conventionally straight foursome and the monstrous queerness of the old dark house’s denizens. By the end, he is firmly aligned with the normals through the cordiality and acceptance of the non-homophobic Penderel. The light of day dispels the shadows, normality is restored. Porterhouse has been abandoned by the chorus girl for Penderel and the two men have undergone another curious role reversal as well: Porterhouse is now the "fifth wheel" among two heterosexual couples; as Callow has observed, a "social and sexual underdog." Or perhaps a literal queer outsider.

MOREAU

Following his sympathetic portrayal of the conflicted and paranoid closet case of Porterhouse, Laughton ceased the reigns of the horror genre, making a return to disturbing form as the homosexual heavy in Island of the Lost Souls, directed by Erle C. Kenton. Released by Paramount4 later in 1932, it is based on the controversially Darwinist sci-fi novella "The Island of Dr. Moreau" by H.G. Wells. Moreau has an affinity with both the queer mad scientists of the Whale Frankenstein films, in which two doctors (one of whom is portrayed by the campy and obviously gay Ernest Thesiger) closet themselves away from society in order to make a man without the aid of womankind. Even more so, Moreau is a progenitor (!) of the mad sadomasochistic scientists portrayed by Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi in later films like The Raven and The Black Cat, which culminate in depraved scenarios in which the actors torture one another to death with apparent psychosexual relish. Moreau also resembles Bela Lugosi’s deranged Dr. Mirakle in Universal’s Murders in the Rue Morgue. Released the same year as both The Old Dark House and Island of Lost Souls, Rue Morgue features themes of genetic manipulation, bestiality and miscegenation similar to Island, and both films feature Lugosi as well.

While inarguably giving one of his best performances- and the film is certainly among the very best of classic monster movies-, Laughton judged Island of Lost Souls to be among his worst films. He would have understandably been disturbed by its extreme interpretation of the homosexual as monstrous, predatory and sadistic and its blurring of queerness with bestiality, genetic mutation, sadomasochism and a general obsession with the unnatural and the abject. In short, the type of role in which Laughton was always at his best; "the very stage villainy that (he) had spent the great part of his career startlingly transforming into genuine evil, with roots in pain and frustration." The seeming critique on the continuing colonialism by Britain and the United States would have interested the radical actor. This aspect of the work is elaborated by the racial representations of Moreau’s "Natives"-- the dark islander exoticism of the "Panther Girl", the Asian traits of Moreau’s dog-like servant Ling, and the thick Eastern European accent of Lugosi’s wolfman-like renegade mutant, among the few of Moreau’s beasts to have mastered speech.5

Whereas in Porterhouse Laughton expertly conveys a man at pains to present an acceptable image of masculinity through an embracing of capitalism, here the ironic metaphor of capitalism is pushed further: Moreau is a tyrannical colonial emperor, but also a swaggering effete voluptuary, secure in his (homo)sexuality. His every gesture speaks of a perverse sensuality. Laughton, "with much winking and smirking, manages to milk every salacious drop out of each line he speaks", Harry M. Benshoff has observed in his study of homosexuality and the horror film, while Callow observes that,

He creates a frightening picture of a gentleman-monster, dabbling with the genetic basis of life, somehow suggesting that he is himself one of his own half-animal/half-humans...His clothes and indeed his very body can barely contain overwhelming impulses and desires...He goes towards his ghoulish task with such relish.

Not surprisingly, the film was disturbing enough to be banned in England, where authorities found it to be "against nature." A full page advertisement in Photoplay provided the following teaser:

He took them from his mad menagerie...Nights were horrible with the screams of tortured beasts...From his House of Pain they came re-made...His masterpiece--the Panther Woman--throbbing to the hot flush of love.

While the ad "simultaneously positioned the doctor as a sadist (and) passion-inspiring figure", a damage-control feature story in the same issue portrayed Laughton as a jolly, fun-loving professional and, to Elsa, a husband of "exceeding warmth." The studio apparently felt the need to separate Laughton from his creation lest the public be too disturbed by the apparent ease in which he so fully inhabited the horrid queer doctor. To further lighten the controversial themes of the script and the bizarre and disturbing undertones Laughton would inevitably bring to Moreau, Paramount launched a highly publicized nation-wide contest to find the young woman who would portray the megalomaniac doctor’s "Panther Girl" creation. The winner would not only appear as the film’s female monster/romantic lead, but would be turned into the beast by Laughton himself, whom the promos portrayed as a man capable of "transforming women in terrifying and desirable ways."

Freed from the interference of conventional law and order, Moreau creates his own hermetic world and "peoples" his island with the pathetic freaks of nature he creates, controlling and abusing them as a retribution against his former homophobic society. Ostracized and banished from his native London, he is an angry god reduced to a cruelty so deep that he is compelled to create a race of underlings to punish for his own sufferings and humiliations. The parallels between Moreau’s warped genetic experiments and the contemporaneous obsession of the psychiatric industry to find a "scientific cure" for homosexuality through some very inhumane means which bordered on the mad science of horror films should not be overlooked.

It is in this hellish empire that Parker, a handsome sailor, finds himself stranded. When he first glimpses Moreau, the doctor is cleverly concealed in a heterosexualized manner akin to Porterhouse’s business tycoon. From a distance, Parker sees a rather large and imposing man in a white tropical suit at the helm of a transport boat, a holstered pistol centered carefully over his groin suggesting at least the illusion of male potency. Laughton’s oddly disturbing androgynous features are hidden by the brim of his panama hat. Rather than a masquerade, this is an assertion of empowerment. Far removed from the Victorian restraints of Porterhouse’s Britain, here Moreau is king, the queer outsider has reinvented himself as a tyrannical oppressor through an urge to control his environment; his strange nature is proudly and overtly paraded instead of repressed. Sporting a satanically groomed goatee, Moreau is at once perceived as very sinister, sexually perverse, and extremely queerly coded. While adopting the trappings of a macho imperialist adventurer and patriarch, Moreau is free to be his own strange, incessantly cruel and vindictive homosexual self.

Moreau immediately sets out to seduce the shipwrecked Parker, telling his protesting assistant Montgomery, who wants to stay on the schooner with Parker himself, "No. I’m taking him up to the house. I’ve got something in mind." Moreau seeks to impress Parker at every turn during their hike to the house, casually snapping his bullwhip at the troublesome "natives" and sending them fleeing; Parker’s valiant protector. To Parker’s comment on his efficiency with the whip, Moreau responds with a lascivious grin, "It’s a hobby of mine", revealing his sadomasochistic nature early in the film. The whip itself, with its implications of rough sex linked to homosexuality, is a curiously loaded prop. The courtship continues as Moreau tries to impress Parker with his scientific insight into the island’s botany. Benshoff has observed that horticulture is often a queer signifier in classical Hollywood horror cinema. By extension, Moreau’s huge genetically engineered flowers suggest by their outrageous size a queerness of epic proportions. The phallicism of the huge asparagus, which the good doctor suggestively chuckles at as he displays it to his attractive guest, takes this line of interpretation even further.

Dr. Moreau confesses to Parker that he has been run out of London for his experiments, his "crimes against nature", and that he "picked up" Montgomery, a medical student facing prison for a "professional indiscretion". After giving up on his seduction of the sailor, the doctor seeks to determine whether Parker can effectively mate with his "Panther Girl" creation, and "scientifically" observes the proceedings, a perverse voyeur. The implications of lewd sexuality abound. Further, the film blurs the lines between sadism, bestiality, miscegenation, and homosexuality, mirroring the public’s view of the "homosexual threat" that associated gays with everything from disease to pansexuality to pedophilia. This blending of depraved sexuality makes a queer reading of the text difficult to avoid.

While certainly possessing a sadistic impulse that is extreme to say the least, it can be argued that Moreau’s cruelty-- The Law he forces his inarticulate creations to recite; The House of Pain in which he vivisects them--are the results of his experiences as a gay man in his native London. His actions on his island of lost souls are but grotesque reenactments of his own sufferings and a vengeance on a world that seems to have singled him out for degradation. Misunderstood, hated and criminalized--It was still an imprisonable offense to be a homosexual in England--Moreau, with Montgomery, finds solace in creating life outside of a heterosexual union, a race of monstrous freaks to dominate and torture. That he is finally abandoned by his life partner Montgomery and set upon and tortured to death by his own creations seems to imply that there can be no safe haven for the queer outsider. Laughton’s final cinematic foray into the monstrous seven years later would dramatically evoke this theme with far greater sympathy.

QUASIMODO

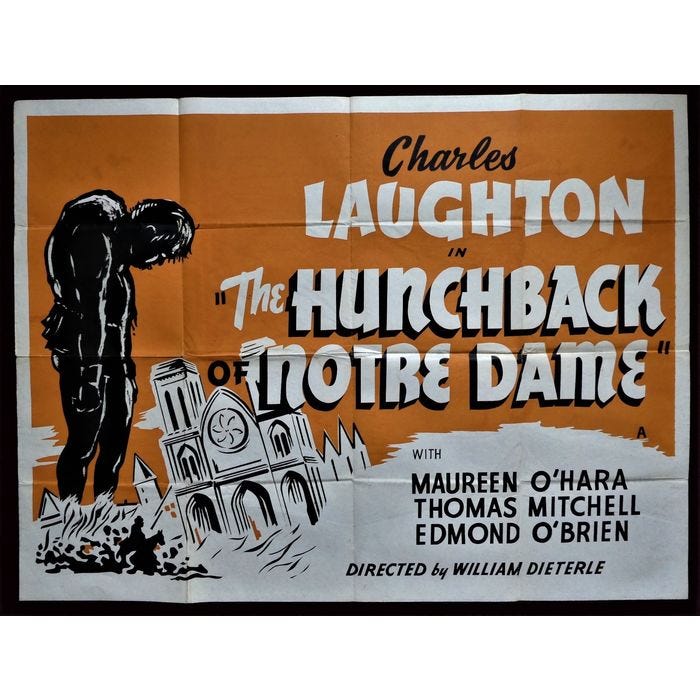

A far cry from the British bachelor dandies of the previous characterizations, Quasimodo is an innocent creature akin to Karloff’s man-made monster in the Whale films. Beneath his freakishness is a pure and gentle soul requiring little more than to exist. Unfortunately, within the world he inhabits, pain and torture await his difference. Here for the first time, Laughton is explicitly revealed as monstrously queer. His physical ugliness is much more intrinsic to the nature of his character’s alienation and the revenge enacted upon his lack of normality is elaborately and tragically presented. In this sense, RKO’s 1939 The Hunchback of Notre Dame, directed by William Dieterle, is without question the most vivid, heartfelt and sympathetic of the three roles examined. The film also contains the actor’s most explicitly charged social commentary.

Quasimodo is a defining characterization for Laughton and remains firmly entrenched in his echelon alongside his famous portrayals of Captain Bligh and Henry VIII, similarly demonstrating a pronounced skill in respectable literary adaptations. He had recently proven a great talent for interpreting Victor Hugo’s works in his acclaimed rendering of Inspector Javert in 1935’s Les Miserables. In Hugo’s Quasimodo, the viewer discovers the cinematic incarnation of the actor’s very real masochism and self-loathing, as well as his perceived ostracism by society. Contrasted with the repression of Porterhouse with his drive for acceptance, and the cruel displacement of rage enacted by Moreau, here Laughton is chained and tortured, wallowing in the shame of his very existence; yet another of his confessionals, as the actor once more "paraded his (to him) physically ugly body before the public, (as) he thrust his (to him) morally and emotionally ugly soul at them."

Callow exposes the hellish depths of Laughton’s self punishing nature during the creation of the Hunchback. The intelligent and sensitive hunchbacked freak, reduced to a monstrous spectacle of suffering in the name of public entertainment, would have seemed a familiar role to Laughton, reflecting his perception of his own life: "Something in the part and the project drew him hypnotically toward the pain it contained." His natural need to suffer apparently consumed him during production. He insisted his hump be as heavy as possible, apparently mimicking the techniques of extreme discomfort to embody the deformed and disabled that had fueled Lon Chaney’s roles, among them his famous 1923 cinematic incarnation of the hunchback. Seeking perfection in his portrayal and appearance, Laughton was so assertive and simultaneouslycondescending to makeup expert Perc Westmore that the monster-maker and his brother at some point trapped the actor in his hump, poured soda in his face and kicked him. This was just the reaction Laughton seemed to have sought, wanting no distinction between Quasimodo’s suffering and his own; and the incident went no further. The filming itself, in the midst of a Hollywood heat wave, was barely endurable for the rest of the cast; under his pounds of hump, make-up and costume, Charles suffered as stoically as the poor chained beast on the platform. As the hunchback is lashed to the jeers of the crowd, Laughton had ordered a production assistant to twist his foot to conjure even more excruciating realism. Dieterle was a willing accomplice to such endeavors, insinuating to Charles that he wasn’t getting the proper degree of suffering across. He later wrote that "when Laughton acted that scene, enduring the terrible torture, he was not the poor crippled creature expecting compassion from the mob, but rather enslaved and oppressed mankind, suffering the most awful injustice." The escalating war in Europe, and Laughton’s own war experiences that never ceased to haunt him added more personal depth to the pain-filled performance. His feelings in this regard were most evoked in the filming of the scene in which Quasimodo rings the bells for Esmerelda’s entertainment. Laughton admitted being seized by an incoherent desire to ring out truth, to arouse the world to the senseless nature of war, and was unable to stop himself until collapsing exhausted. "He risked madness and physical collapse to fashion from his own psyche an image of the human condition." Lanchester recalled that he "took torture over and above what was needed--a sort of purging of his human weakness and general guilt...for an overall insufficiency of perfection in life and work."

The finished work is arguably Laughton’s crowning achievement, the fullest realization of the actor-auteur’s outsider themes. Highly critical of white patriarchy and government altogether, the film has a decidedly anti-authoritarian stance to its narrative and themes. The written statement that follows the opening credits reveals the film to be an admonishment against "superstition and prejudice" and proceeds to portray the attempts of the evil and corrupt Frollo, a high judge in the Paris courts as well as Quasimodo’s keeper, to convince the King of France of the danger embodied by a small people’s press. Though shut down in the end, the press becomes the literal voice of the underground, used to print communiques and leaflets on behalf of citizen’s rights, eventually swaying the King himself to more liberal beliefs. Frollo refers to the poets and philosophers given expression by the press as "heretics" and sees the literature as a threat to the kingdom. The King responds with criticism of the Church, calling it the "handwriting of the past" and the press that of the new. Unfortunately, the rather good-natured and free-thinking King’s power is undermined by inhumane laws and a corruption within his offices which the repressed Frollo, played by Sir Cedric Hardwicke, is determined to uphold in order to maintain his fascist agenda. Any good that his kingship’s authority might propagate is kept in check by the bureaucratic structure.

“The ugly is very appealing to man. Its instinct. One shrinks from the ugly, yet wants to look at it. There’s a devilish fascination in it. We extract pleasure from horror.” So the King of France tells Frollo in a self-reflexive statement of the horror genre’s appeal that adds another layer to the critiques of superstition and racial/social prejudice. "Witches, sorcerers and gypsies" are referred to in one breath, and the "Fool’s Day" celebration begins with a request that "Africans come forward," the authorities equating the foreign with both stupidity and the supernatural. Civil disobedience by the disenfranchised is portrayed early in the film, as a clan of gypsies are refused entry to Paris on the basis of their race and proceed to heroically rush the gates to take part in the festivities. The lusty anarchic merriment of the Fool’s Day revelry looks ahead to the gatherings of the 1960s, even featuring an agit-prop guerrilla theater troupe that attempts to awaken the masses. 6 The film is further aligned to the left in its subversive contrasting of a corrupt and evil government with that of a heroic subculture collective of racial minorities, artists, and thieves and their people’s press. Although the radicals emerge as the heroes by defeating Frollo and restoring power to the masses, Quasimodo, whose actions are intrinsic to their victory, is not accepted into their world either, but seems doomed to a solitary existence in the bell tower.

The fey Frollo immediately recalls in demeanor and appearance the queer scientist couples of Frankenstein and also Lugosi and Karloff in films like The Black Cat and The Raven. His cruel offering up of an unsuspecting Esmerelda to the brute is as routine a plot device within the realm of classical horror film as the token "beast in the boudoir" sequence, and arguably a queer voyeur variation of it. Frollo’s corruption, racism, sexual repression and cruelty are invariably intertwined into the worst possible representation of an authority figure. As Quasimodo’s caretaker, he could easily lighten the monster’s burden of oddity through human compassion, the Hunchback instead is a mascot of sorts to demonstrate an empathy of which the judge is hardly capable. He allows Quasimodo to be treated as a freakshow and accepts the community’s perception of the innocent brute as "possessed". Quasimodo is someone to suffer for Frollo’s own horrible sins, and the government official emerges as the true monster villain of the piece.

There is an undercurrent of lacivious sadism in Frollo’s role as the young hunchback’s keeper. The exact nature of their relationship remains ambiguous. While he cruelly interrupts Quasimodo’s happy moment as the King of Fools, Frollo also turns a blind eye when his charge is unjustly punished before the mob, unwilling to demonstrate any compassion, much less affection for him in the light of day. Like Moreau, Quasimodo is betrayed and abandoned by his only (male) companion; and like Porterhouse, the portrait of Quasimodo cannot stand distinctly apart from his involvement and interaction with another male character whom he is simultaneously likened to and contrasted with. More so than in the previous entries, askew sexuality is heavily coded. Frollo’s repressed and confused sexual longings eventually lead him to sentence to death "for heresy" a gypsy girl who rejects his advances. Quasimodo, doomed to a life devoid of any emotional relationship, much less sexual gratification, gives Notre Dame’s bells the names of women and bestrides them frantically in an orgiastic state. The persecution of Quasimodo is a gender-blending double for that of the gypsy girl; both are unjustly brought before the public for humiliating punishment due to the corruption of Frollo, both find grim solitary sanctuary within Notre Dame’s walls. Esmerelda’s monstrous threat as a beautiful sexually liberated woman and as a racial outsider are as threatening to the prevailing ideology as Quasimodo’s ghastly deformity, and Maureen O’Hara’s physical perfection mirrors the pure soul of the outcast brute. Quasimodo exhibits no sexual yearnings for her; she is simply a fellow outcast and refugee and someone who showed him kindness during his flagellation; one whose beauty oddly reflects his hideousness, as he claims to have never felt so ugly as when admiring her.

While rescuing his female doppelganger from the same fate later, the hunchback is unable or unwilling to save himself from a lashing and public humiliation in the Paris square. Quasimodo is Laughton, chained to the stage, suffering for the pleasure of the masses. Like the beauty of the Hunchback’s bell-ringing finesse, so the freakish actor brings beauty and art into the world in an unconventional form. However, his queerness is deemed appropriate only as a tortured spectacle.

That he is crowned the King of Fools has certain significance also. “The fool,” writes William Willeford, “has antecedents and relatives among a wide range of people who in various ways violate the human image and who become a modus vivendi with society by making a show of that violation." Psychoanalyst Annie Reich examines the Fool as an historical embodiment of "the structure of grotesque-comic sublimation...Confession and self-punishment are combined with aggression against others...Probably even acclamation from outside is incapable of preventing anxiety and a deep depression. The forces of the actor’s conscience are too strong and therefore he is overwhelmed with anxiety and guilt...the grotesque-comic performance is characterized by an extreme sexualization of the relationship between actor and public... Whenever someone is talented in caricature or grotesque-comic acting and the like, a tendency to self-exposure creeps in beside the wish to expose others." Laughton, court jester to the world, "disturbed and appealed in equal measure."

Finally, the intense longing for a physical beauty he can never possess, coupled with his resignation to exist in the solitary shadows of the outsider’s lonely realm, makes Quasimodo’s questioning of the cathedral’s gargoyles that closes the film especially poignant: "Why was I not made of stone as thee?"

It is for good reason that Callow splits Laughton’s career into two distinct halves, and that Hunchback marks the end of the first. Not only was it effectively his last entry in the fading classical phase of the horror genre that so suited him, it also proved to be something of a final eradication of certain demons within him; "one last, glorious offering up of his guts and his bowels on the altar of his cruel god" as Callow eloquently states. His career as a bright light, albeit a very dark one, among the often generic offerings of other screen stars of his time was essentially over, and like Lugosi and Karloff, he was sentenced to self-parody in a string of horror-comedies; "he, who had given flesh and blood to the most genuinely terrifying ogres of the screen, monsters from the collective unconscious, becoming a star of children’s movies, a sort of harmless ogre." But the darkness was always there, resurfacing in his roles in noirish fare like Jamaica Inn, The Suspect, and The Big Clock. And his masterpiece may well be a film he did not appear in but was a passion project he directed: The extraordinary and eerie 1955 film noir Night of the Hunter starring Robert Mitchum at his most sinister and charismatic. His worldview continued to be one tied to horror, or so it would seem.

Porterhouse’s deeply tormented acceptance of the dominant ideology; the contemptuous excess of Moreau in a sub-human colony of his own creation; the unjust punishment and self-punishment of the Hunchback; these were but three portrayals within a narrow genre in which Charles Laughton allowed audiences a gaze into a secret complex soul that mirrored their own dark longings and inner turmoil. As the years progressed, he would increasingly turn back to the stage, his first and most beloved home, and also to reading tours, a precursor to the current trend of spoken word performance art, which appeared to give him much joy. The need to perform remained, but the need to reveal had passed; "Now when he wanted to escape himself, he did so by assuming the well-known, well-respected form of Charles Laughton, public person, rather than descending into the amorphous sludge of his inner darkness, hoping perhaps to catch a monster or two, and take the pressure off. His alliance with the void (Cocteau’s phrase) was off; he was now for the light." Although it was not in Laughton’s nature to be at peace with himself or his environment and "his life had been defined by his world’s view of sex," the actor’s Queer Outsider persona was largely absent in many of his later works. He found some satisfaction in collaboration with the avant-garde playwright Bertolt Brecht, a fellow outsider and kindred spirit who also had no use for social conventions and explored themes of Verfremdungseffekt-- Brecht’s own concept that suggests "alienation...The-making-strange, the-making-foreign, seeing in a new way, from a different angle.” Indeed, what Laughton had been doing on stage and screen all along.

Kierkegard observed that the artist cannot change society but can only express what is sick. Perhaps a combination of the exorcisms he had submitted himself to in his early roles, and the somewhat more tolerant queer-friendly times that followed gave him a peace he had been unable to attain previously. The intimate forum of the reading tours was certainly a new arena for expression, and instilled in him a deeper awareness of his own worth. He no longer felt compelled to hide behind the coding of monsters, madmen, perverts and neurotics to present himself. He had seemingly grasped the power he held over his audience and its queer attraction to him, a power his first monstrous creation Crispin had acknowledged all those years ago:

You have laughed at me, mocked me, insulted me--you and all the world: but now you are mine, to do with as I will. An old, fat, ugly man... I prick you and you shall bleed. I spit on you and you shall bow your heads... I, the ludicrous creature that I am, have absolute power over... you...I can do whatever I like with you...the last shame, the last indignity, the uttermost pain.

It is a supernatural power that continues to challenge audiences and provoke interpretation and discussion. Laughton is a wayfaring stranger from the dark side who will continue to excite and disturb the mob.

Notes:

The following biographical sketch draws predominately from Callow’s work. Additionally, the term "queer" as defined in this essay is a personal interpretation; a hybrid of the traditional connotation of strangeness and the unexpected, and that of the radical sexual and social politics expressed by proponents of "Queer Theory."

The back cover of the Kino VHS edition of the film intuitively if obliquely describes the Porterhouse character as simply "a man with an odd fixation on his deceased wife."

It is worth emphasizing here that Elsa herself is best remembered for her portrayal of monstrous femininity in Whale’s 1935 masterpiece Bride of Frankenstein.

Although often erroneously credited as a Universal classic. Hollywood horror films dating from the 1920s through the 1950s are generally referred to as “Universal Monster” movies no matter the studio that actually produced and released them.

Four decades after its controversial release, Island of Lost Souls would become the primary inspiration for the weirdly asexual Sci-fi punk band Devo (short for de-evolution) and provide the title of the group’s song “Are We Not Men?” which also acted as Devo’s bizarre mission statement. Later songs like their hit single “Whip It” also suggest the influence of the film’s themes.

Indeed the very same Paris streets the film portrays overrun with the revelry of the masses became a modern reality in 1968 when French students and workers revolted and effectively took over and shut down large portions of the city for two weeks. Despite images of the 60s that the film evokes upon a contemporary viewing, the troupe’s performance, with perceived Beat-style drum and poetry raps and dancing skeletons, in reality reflects Dieterle’s German Expressionist roots, and that movement’s ties to the earlier socio-political shenanigans of Dadaist theater. However, many of Laughton’s contemporaries have noted the actor’s generally "revolting, untidy clothes"(Callow, p.17) and a very real bohemian sensibility that prefigured the Hippies and Yippies of three decades later.

Sources:

Another well written article

I loved the Charles Laughton article AND PICS!! He was definitely one of a kind…such a versatile actor… Your article made him seem human and very approachable…extremely unique looks for such a famous actor! So many extra details that made him seem to come to life when I was reading it…👏🏻👏🏻👏🏻🙋♀️