Two Lane Blacktop: The Wild Ones of Fort Worth and the Triumph of the Wheel 1953-57

An Excerpt from Philip's Shadow: A Subcultural History featuring the Actor Philip Norman Fagan

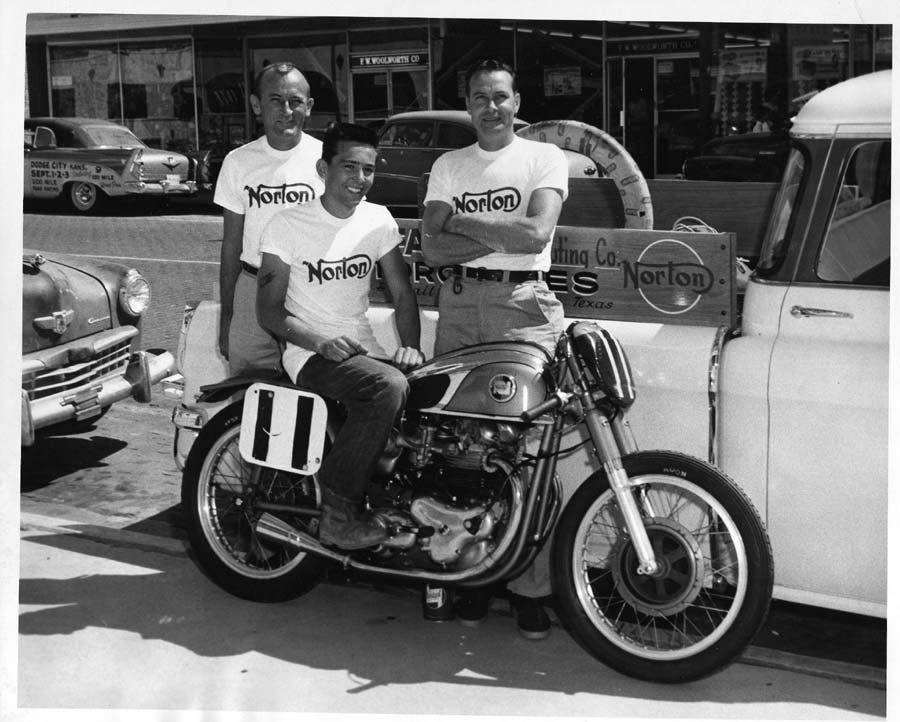

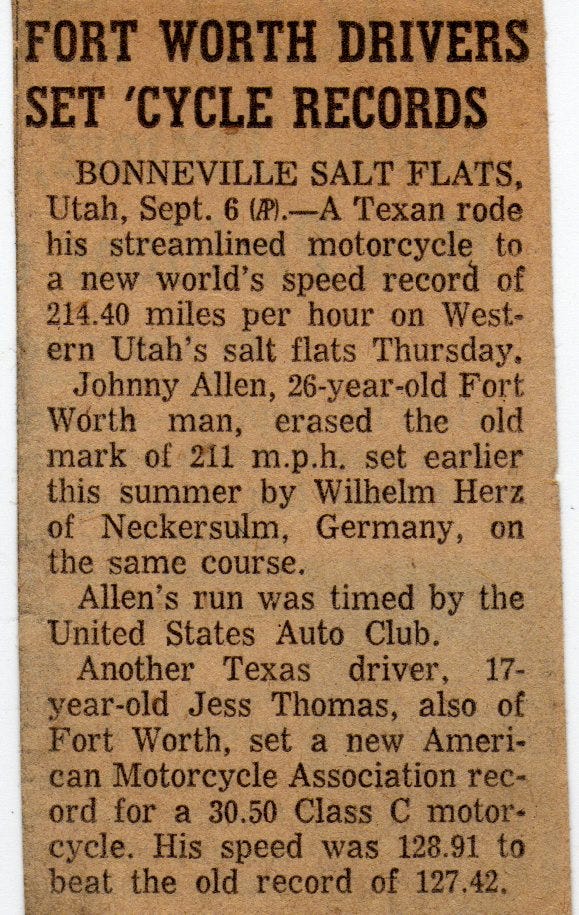

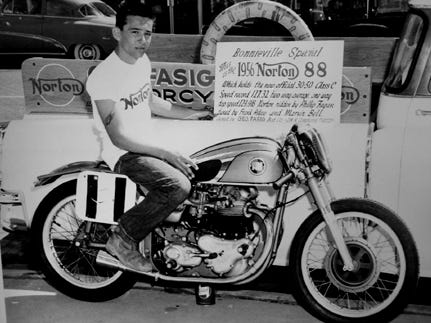

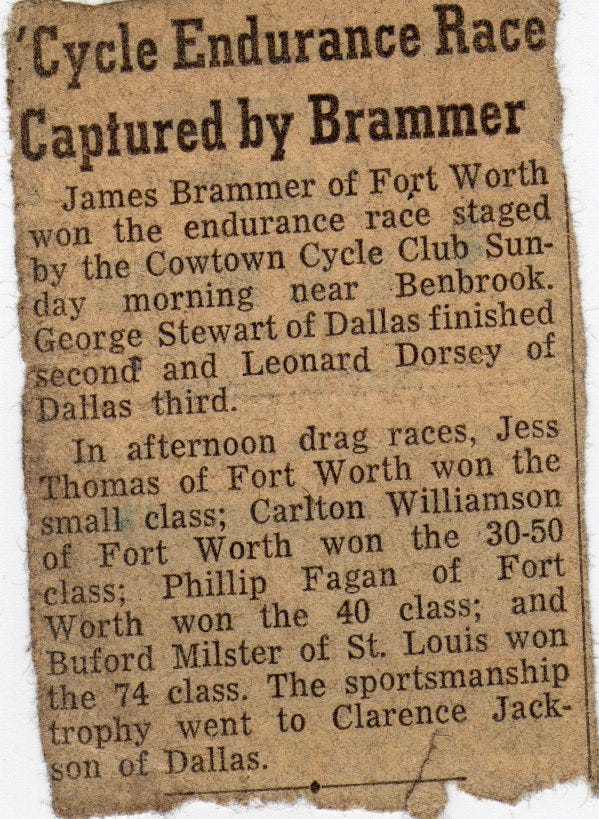

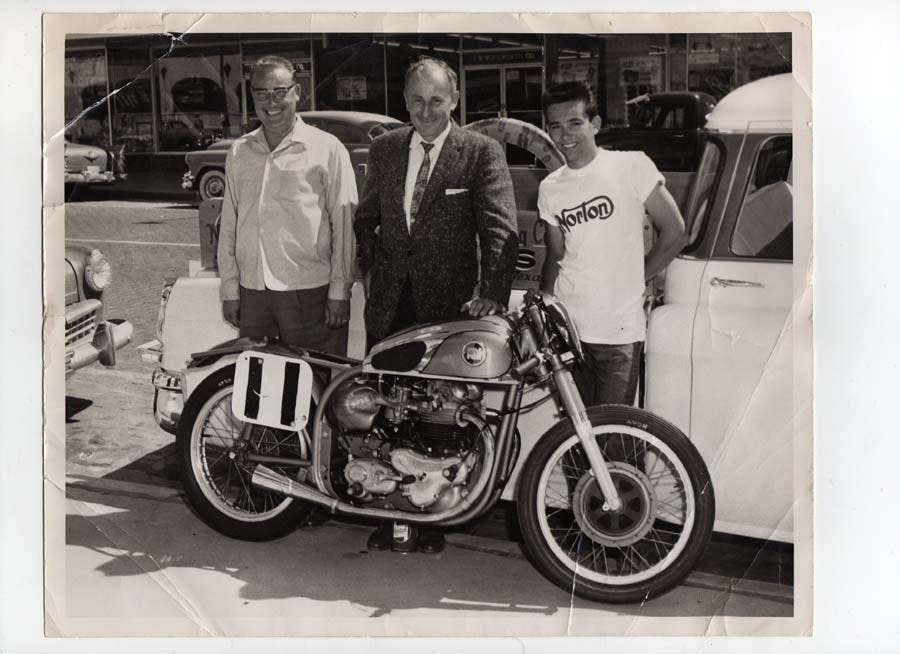

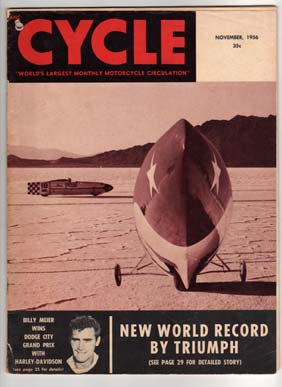

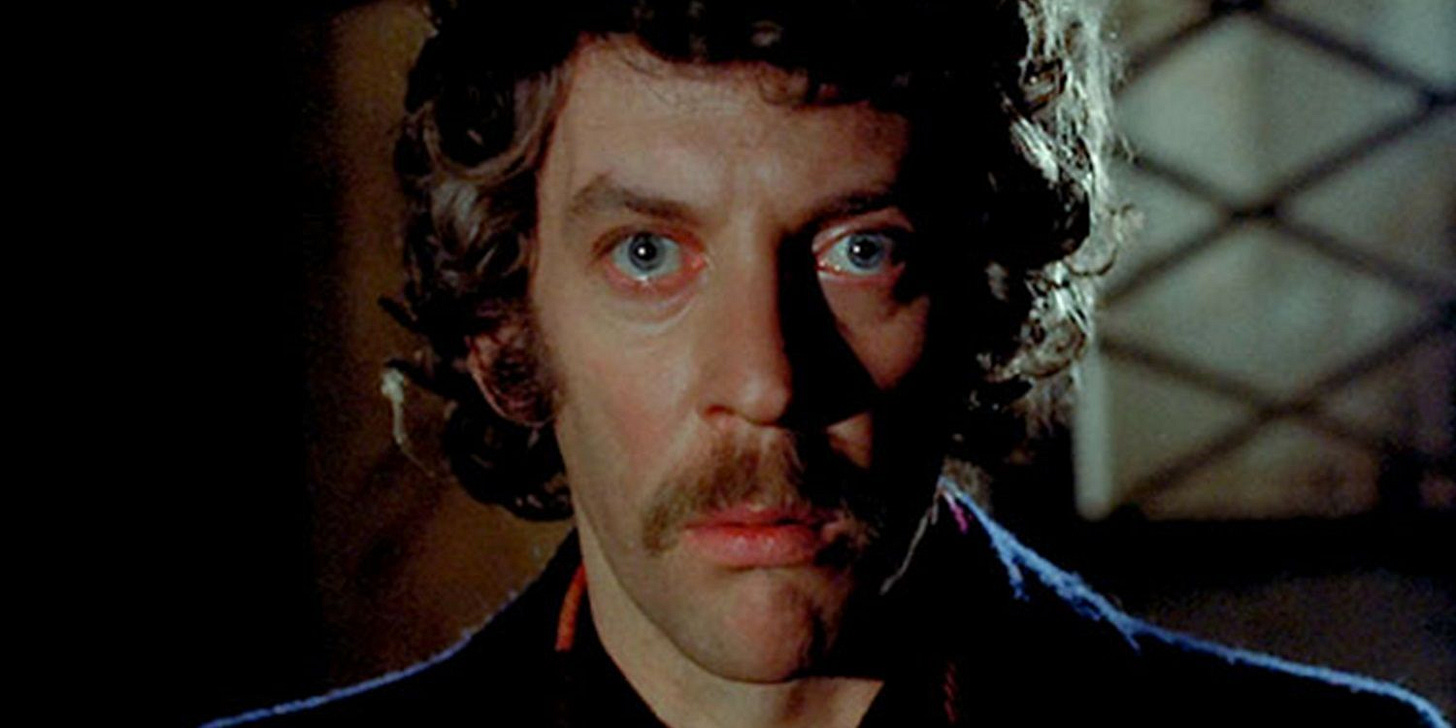

My late uncle Philip Norman Fagan would have turned 86 this month. To celebrate Philip as well as the release of Jeff Nichols’ awesomely hyper-masculine Scorsesian throwback flick The BikeRiders this past weekend- probably the best new major American film I have seen thus far in 2024-, I present here a related piece of motorcycle history. The following is an excerpt from the book I wrote about Philip and the vast array of underground subcultures he explored throughout the 1950s and 60s. Before his close friendships and collaborations with Alejandro Jodorowsky, Andy Warhol, and William Burroughs and his later wanderings as a solitary monk in war-torn Southeast Asia, Philip played a vital role in the rowdy motorcycle club culture of Fort Worth, Texas and went on to set a world speed record on a customized 1956 Norton 88 at the Bonneville Salt Flats. He led an exciting dozen lives in as many years. This book can be purchased from the Evil Empire HERE. I’m very grateful for the interviews I was granted by the former members of the Iron Horse MC. Thanks as always for reading. Now, start your engines and let’s ride…

Two Lane Blacktop: The Wild Ones of Fort Worth and the Triumph of the Wheel 1953-57

A skittish motor-bike with a touch of blood in it is better than all the riding animals on earth, because of its logical extension of our faculties, and the hint, the provocation, to excess conferred by its honeyed untired smoothness. [i] ~ T.E. Lawrence (“of Arabia”)

“Black Rebels Motorcycle Club. That’s cute. Hey Johnny, what are you rebelling against?” Brando: “Whaddaya got?” ~The Wild One

The concept of the “motorcycle outlaw” was as uniquely American as jazz. [ii]

~Hunter S. Thompson

If you’ve ever heard a Triumph with megaphones accelerating up through the gears, then you know what Allen Ginsberg was talking about when he described a “saxophone cry that shivered the city down to the last radio.”[iii] ~Detroit Free Press, March 1994

An embrace of “Carnivalism,” of irrationality, individuality, absurdism, and play, as a reaction to and an antidote for the constraints of responsibility imposed by the established order has been at the root of countercultural activity since time immemorial. Soviet era philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin locates the phenomenon’s roots in Medieval Europe, when the peasantry embraced a sort of double life. A man was first and foremost a citizen, churchgoer, and worker within a subservient and officially condoned hierarchical existence. On festival days and in the marketplace, beyond the watchful eye of kings and clergy, he cut loose and howled at the moon, indulging in various combinations of drunkenness, lewdness, blasphemy, grotesquerie, music, dance, improvised play, costume, daredevilry, laughter, unpredictability, and general Dionysian revelry. For a day or two, the peasantry ruled the town with gleeful abandon, even crowning their own “King of Fools” on the annual Fool’s Day to assert their antiauthoritarian autonomy. As long as order was soon restored and the mass chaotic freedom of individualized behavior didn’t bleed over into the normalcy of non-feast days, Carnivalism was a socially acceptable and societally condoned behavior; albeit a restricted one. Although Carnivalism was essentially an inextricable component of primal human nature, it was also a routine put in place by the established order that allowed the peasantry to blow off steam from time to time, acting as a preemptive strategy for preventing revolts and uprisings, offering a socially sanctioned if short-lived annihilation of the responsibilities, drudgery, and mores of codified daily living. Such rituals offered a vital and necessary temporary expression of the human spirit that ultimately made the status quo repression of that spirit somehow tolerable. A man was allowed to act the fool, knowing that he must soon return to the fold of established social and moral norms or perish. A man’s official life, and therefore the greater social and cultural order, was maintained by both the memory of and anticipation of the expressive freedom offered by the escapism of festivals and marketplace “life.”

While even the most rigidly respectable society man of the Eisenhower years needed the occasional dose of socially sanctioned abandon (illicit if accepted love affairs, the three-martini lunch, holiday parties, sporting events, circus sideshow midways, poker, movies and TV, etc.), others would not- and often perhaps could not- live without a near constant embrace of the Carnivalesque. In many respects, Philip Fagan would come to epitomize a kind of Beat-style medievalist, rejecting the modern world and traveling on foot throughout adventures in strange ancient lands with nothing more than a song and a prayer. At a very young age he began seeking ways to exist within the confines of society while attempting to subvert its shackles of rationality, conformity, and routine. In Fort Worth, in the middle 1950s, he found an outlet in the world of motorcycle clubs and racing.

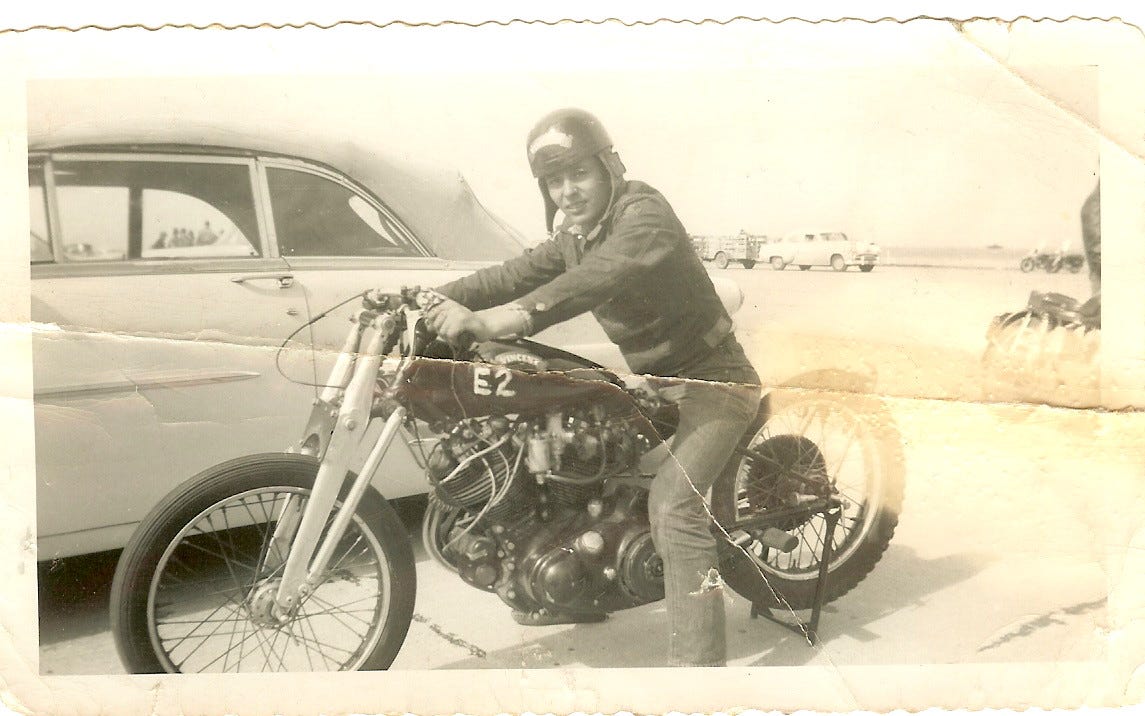

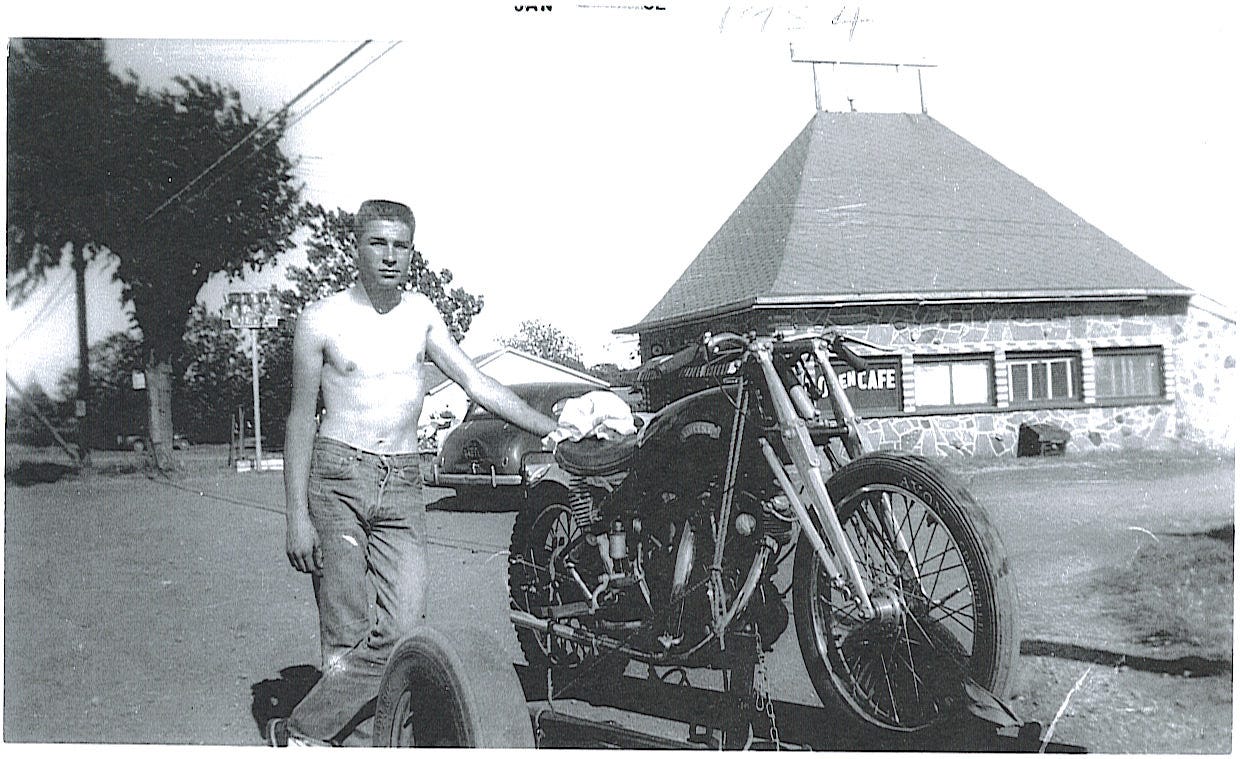

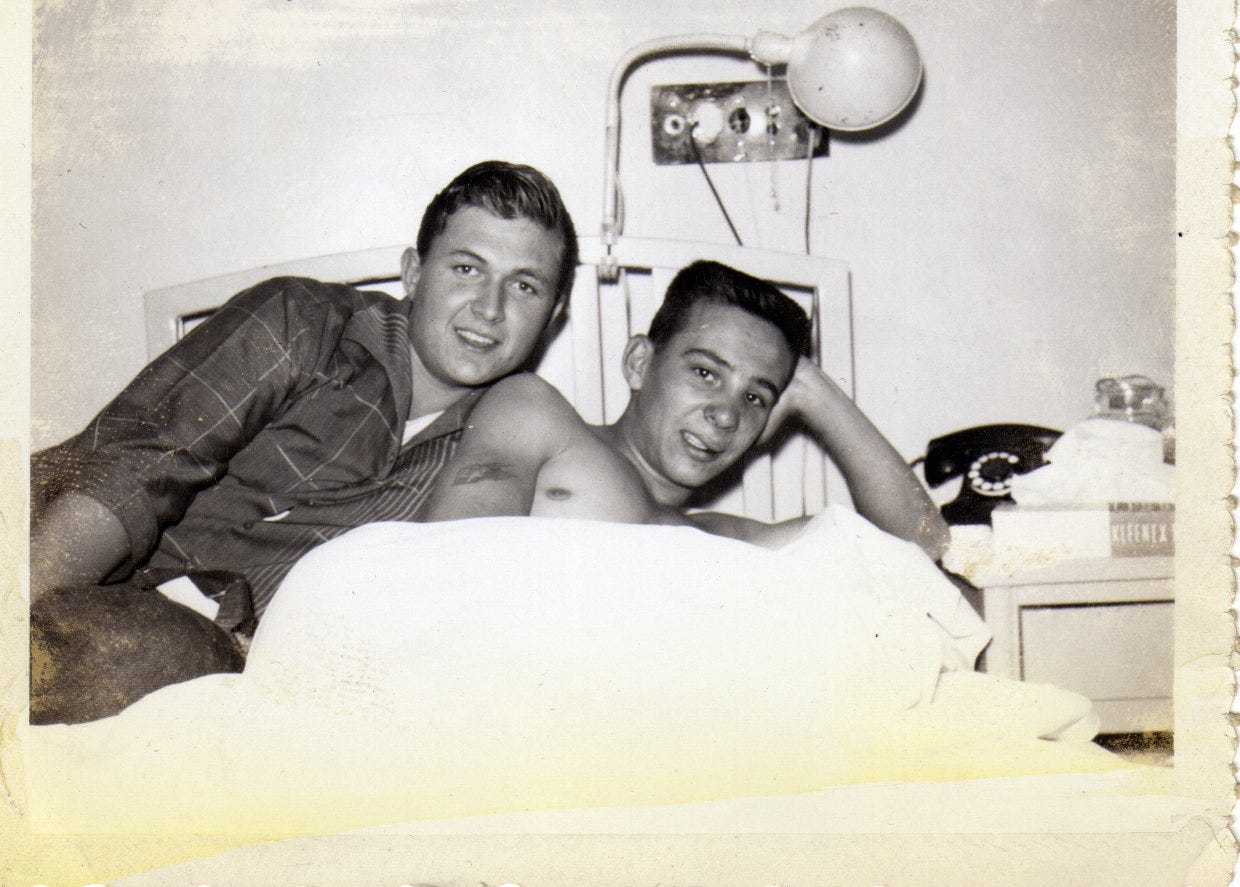

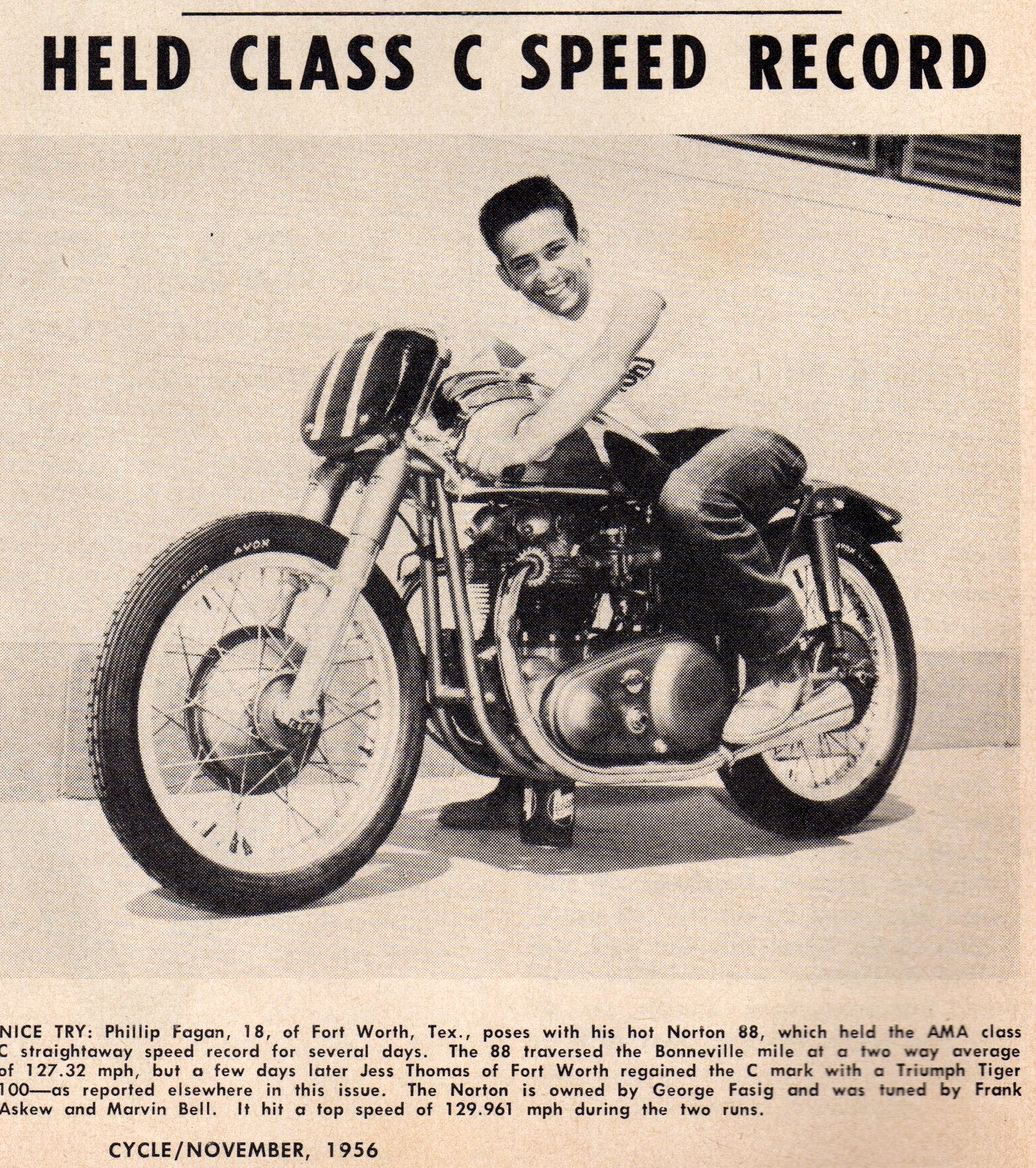

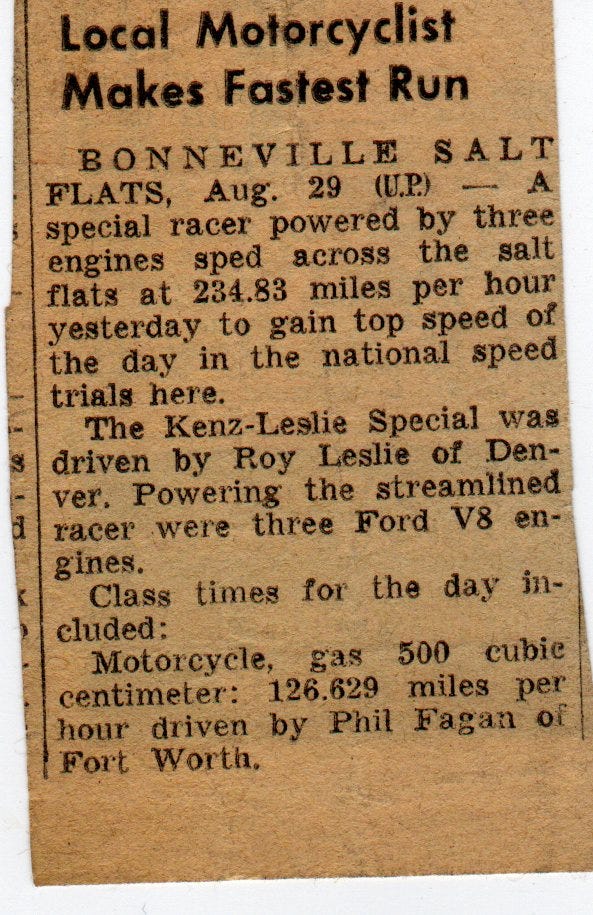

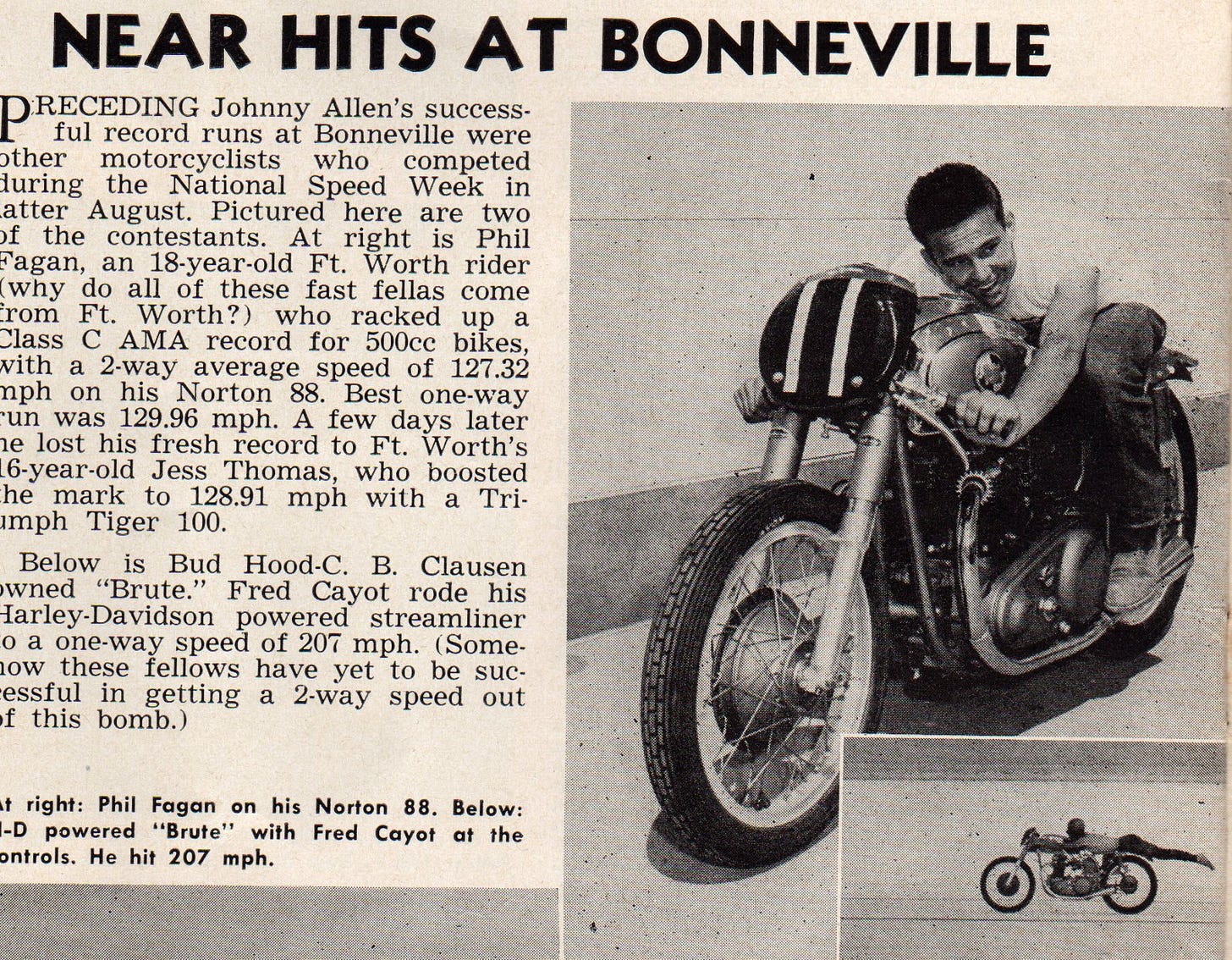

At an early age, I inherited one of Philip’s motorcycle helmets, a gift from my father along with my first cycle, a street legal Suzuki 185 dirt-bike. Philip’s hand-painted helmet was certainly one of a kind. It was open-faced with a chin strap and painted bone-white. But, as if the helmet was itself a human head, the top was painted to resemble a torn scalp and skull, revealing bloody brain matter within the tear. A large black spider seemed to feed upon the flesh, brain, and blood that comprised the wound. The object seems a prophetic symbol of what would become Philip’s increasingly tormented psychic state, his own mind seemingly under attack from unseen dark forces. If spiders and gore were not perverse and shocking enough, the shape of the wound was distinctly vaginal, rendering the contents of the arachnid’s meal ambiguously erotic and even necrophiliac. It seems unlikely that Philip wore such a thing in the middle 1950s; it is far too over the top. More than likely he wore it later in the less censorious California of the early 1960s, but Carl Busbee, who roomed with Jerry Fagan at the University of Texas in Arlington in 1960, remembers Philip sporting the infamous crash protector around that time, presumably home on leave from the Navy. Several years before that, Philip was making motorcycle history, including setting a Class C cycle speed record at the Bonneville Salt Flats.

Sometime during the same period, he had emblazoned on his right bicep the ultimate outlaw biker icon, a skull and wings tattoo. Oddly, only one person I interviewed about my uncle ever recalled the tattoo, and when and where he received it remains a mystery. There were quite a few tattoo parlors in Fort Worth in the Fifties and it would appear that he got his in 1956 around the time he began racing Norton motorcycles for George Fasig. He didn’t show it off to his estranged girlfriend Louise the year before, but was soon proudly flashing it in photos when posing with his record-setting Norton. With the fresh ink, he in a sense joined a fraternity of those outside the mainstream; the world of carnies, sailors, thieves, and the more bad-ass biker element. It was an assertive, subversive and apocalyptic statement and as rich a symbol as can be imagined for a short, fast, intensely-lived life. Or as Ronald Tavel, his friend and collaborator from the Warhol orbit later saw it, a chilling portent of Philip’s encroaching doom.

At the turn of the Twentieth Century, American motorcycle technology closely paralleled the modern inventions taking place throughout Europe that began with the motorized two-wheeler of German inventor Gottlieb Daimler. American motorcycles were but a drop in a wider sea of motorbike engineering that included innovative technology from Belgium, Britain, Czechoslovakia, France, Hungary, and Italy. In the US, Indian was established in 1901 followed closely by Harley Davidson two years later; however, the early American motorcycle industry was intensely crowded and competitive. Equally well known in the period were brands like Crosley, Henderson, Pierce, Pope, Merkel, Thomas, Orient, AMC, Cleveland, Ace, Thor, Thiem, and Excelsior. But the competition cleared out early on when four-cylinder prototypes of the modern cycle arrived and Indians and Harleys proved the only real American forces to be reckoned with in speed and endurance competitions like the New York-based National Endurance and Reliability Contest and the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy. Such high profile events launched the cycle into international consciousness and the machines quickly became a popular pastime for working class American riders and spectators alike. Cycles were a thrilling new invention and a hot fad, spawning enthusiast clubs and throngs of family-friendly “gypsy tour” groups throughout the nation, which generated their own subcultural jargon (header, mile-a-minute, ton-up, slant artist, riding pillion, road rash, lid, etc.) culminating in the establishment of the American Motorcycle Association in 1924. But not everyone was thrilled with the latest miracle of modern science. From the beginning, the loud, smelly new beasts of city riders were derided as antisocial nuisances, a source of noise and air pollution that frightened horses and prompted swift angry responses from American civic groups and religious leaders. “Get a horse!” was the battle cry of naysayers. But like the symbolic horse before them, the freedom and excitement offered by the new machines seemed to many to represent the spirit of America itself. Cyclists were the newest breed of brave, if foolhardy, rugged individualists, as The New York Times remarked in 1913. “Motor cyclists eat and sleep and talk like other folks, but at times they can’t help feeling that they haven’t as long to live as the ordinary man. And they are right. They are a fearless lot, brave enough to wear their lives on their sleeves, and have nerves as unimpressionable as flints.”[iv] While Indian dominated the race track, Harley carved out its niche as the bike of the American road, enacting a clever campaign to highlight the quiet engine of the “Silent Gray Fellow” and the company’s efforts in noise-reduction technology.

Cycle racing became a popular regional sport in the nation’s towns and cities around 1910, graduating from dirt horse racing tracks to wooden “murderdromes,” so called for the perilously steeped bank tracks and high fatality rates among competitors. In addition to the pulsing excitement of sheer speed and deafening cacophany, “motordromes offered still another thrill to the people who crowded the stands,” writes Michael Dregni. “Blood. Board-track races were like Roman chariot races of yore. A burst tire at full speed could send a motorcycle pilot careening across the track, and stories of horrific crashes at other motordromes were part of the pull to the crowd. It was the noise, spectacle of speed, and sheer bloodthirstiness of motordrome racing that had whipped the local preachers into a frenzy usually reserved for visions of the coming of the Antichrist.”[v] The combination of such clerical and civic outrage, bloodshed and death as popular entertainment, riders with nicknames like “Demon” and cycles with monikers like the Cyclone contributed to the violent, sinister and subversive image and appeal of motorcycle culture. Motorcycle daredevilry and stunt riding became standard fare for travelling circus sideshows and Wild West shows (“The Wall of Death”) as well as movie adventure serials (The Perils of Pauline, 1914-67; The Hazards of Helen, 1914-17). By the 1930s, competitive showmen of the Depression era upped the ante on outrageous derring-do, incorporating lions, rattlesnakes and other dangerous animals into their Wall of Death and murderdrome spectacles. For spectators and showmen alike, motorcycle sports thrived on the thrills of danger and death.

Meanwhile, having nearly whittled down the national competition to a two brand war, Harley and Indian were under constant assault from machines across the pond. The same crowded craze of motorcycle manufacturers that swamped the US played out in Europe as well, but the Brits had been at the top of cycle invention and innovation since the 1890s. Companies like Ariel, BSA, Norton, and Triumph continued to produce some of the world’s fastest and smoothest-running cycles, stealing both records and customers at home and abroad. Norton’s famous racing team (whose ranks Philip Fagan would symbolically join with his Class-C record of 1956) took home 14 Tourist Trophy victories in the 1930s alone and became Harley’s number one nemesis in the States. American cyclists became increasingly loyal to the superior offerings of the Brits and the competition between the English and American manufacturers eclipsed the previous one between the stateside companies. Triumph in particular proved strangely adept at negotiating that most of American of cycling events, besting Harleys and Indians at their own game, as cycle historian Lindsay Brooke notes:

…Flat tracks at county fairs. The backbone of the American motorcycle sport since the beginning. While endurance runs, TTs, and regional speedway racing were an important part of the pre-war scene, nothing matched the spectacle of riders locked in thunderous power slides, battling wheel to wheel on mile and half-mile dirt ovals. Flat track simply defined U.S. racing…Harley Davidson and Indian. Both were survivors of a once-thriving American motorcycle industry that had been all but decimated by the inexpensive automobile of the 1920s and the Great Depression of the 1930s…As the U.S. market struggled against lean times, so did racing. If motorcycle racing, indeed motorcycling itself, was to prosper again, a rebirth was needed. So in 1933 AMA czar E.C. Smith…revamped their entire program. Smith’s goal was to revitalize racing by encouraging privateers. The solution was to adopt a new racing formula. Called Class C, the new rules stipulated that racing bikes be based directly on standard production machines. To level the playing field, at least 100 examples of any new model had to be advertised and sold before any units were approved for competition. [vi]

While leveling the playing field to mass-product models, the AMA added a stipulation that disclosed their unsurprising bias toward American manufacturers: Flathead American engines were allowed to be significantly larger than the overhead-valve engines favored by British and European bike makers. In flat track events, Harley flatheads were limited to 45 cubic inches, or 750 cc, while overhead-valves were restricted to 30.5 cubic inches, or 500cc. Another AMA addendum attempted to counteract the Limeys’ superior gear-shifting engineering. However, such advantages were ultimately illusory. The stealthy British bikes were so much lighter and more maneuverable than the American V-twins that the Class C was inadvertently ready-made for the British invasion. The quality of Triumph’s assembly line models was so high that such bikes were often able to make good showings at races and speed events without the aid of regulation speed kits and custom parts. Bikes like the Speed Twin and Tiger 100 were proving a force to be reckoned with at AMA stateside races before the Second World War.

Almost from the machine’s inception at the turn of the Twentieth Century, the American motorcycle industry exploited the adventurous desires of American youngsters. Indian produced a boy’s bicycle complete with fake gas tank in 1913, while Harley Davidson followed three years later with its own brand name bicycle. Both shrewdly offered a stepping stone product for young potentially brand-loyal future motorcyclists. Such shrewd marketing was a two-way street, with the Schwinn bicycle company taking over the popular Excelsior and Henderson motorcycle brands, and bicycle dealers across the nation began pushing motorized two-wheelers to the front of their showrooms. By this time, cycles had also become a successful device in the boy’s adventure literary genre. Tom Swift and His Motorcycle was an exciting 1910 entry in the popular series featuring the young inventor-adventurer, and the Boy Scouts of America got in on the action in 1912’s Boy Scouts on Motorcycles which had its young heroes assisting the US Secret Service in China. Also emerging during the War years was a boy’s adventure series that put bikes front and center called The Motorcycle Chums. The series’ exploits were those of a group of teen bikers “who take on everything from the rugged wilderness of Yellowstone Park to the Santa Fe Trail…'thrilling adventures with moonshiners, poachers, and ‘nomadic apaches.’” Big Five Motorcycle Boys, a similar series, featured crime-fighting bikers eventually riding their machines on the front lines of World War I.[vii] By the Second World War, Marvel Comics’ Captain America was atop his steel steed keeping up the good fight against Hitler and the Red Skull on the European front, while other biker superheroes included Batman and Ghost Rider.

In World War I, cycles often replaced horses on the battlefield but were primarily used to deliver dispatches and transport the wounded along the front lines. The US Army also enlisted them in their pursuit of the revolutionary leader Pancho Villa in Mexico, while on the home front cycles slowly became a vital component of big-city police forces. By WWII, bikes were a commonplace attack vehicle on both sides of the battlefield, including models with tank tread wheels and parcel-sized folded jobs that were parachuted to troops trapped behind enemy lines. Many American troops were first exposed to Europe’s two-wheel marvels in the trenches; not only the Brit bikes of their fellow Allies, but also Germany’s BMW and Zundapp brands and Italy’s Moto Guzzi. Back at home, the major American bike brands were quick to seize the marketing potential of their contribution to the war effort, featuring endorsements from biker soldiers in their ad campaigns. Such testimonials were no doubt highly effective, simultaneously asserting the machines as a highly reliable wartime survival tool and a coveted commodity which the returning vet could not wait to buy for himself upon reentry into civilian life. Across the pond, brands like Norton also stressed their wartime service in ads, likening their Big Four machines to the Big Four victory alliance. The Second World War effectively ended the decades-long competition between Harley and Indian, with the latter never quite recovering from overextending itself on behalf of the war effort. By the end of the Forties, the Indian motorcycle was often no more than a decal on the gas tanks of British Nortons and Royal Enfields trading on the popular American brand name. But the British invasion of the late Thirties and Forties had a lot more competition to offer Harley than simply passing themselves off as the last gasps of its dying arch foe. More and more American riders were turning to British bikes like BSA, Matchless, Norton, and Triumph, particularly after the Vincent Black Shadow shattered Harley-Davidson’s coveted record at Bonneville Salt Flats in 1948, an event widely heralded in the mainstream press.

American motorcycle gang culture as we know it today began in earnest after World War II when, according to legend, members of US bomber squadrons like the Hell’s Angels and frontline cycle soldiers returned home to a vastly transformed homeland. Unable to shake the addiction to speed, danger, and general hell-raising that had defined their wartime exploits, the wily vets hit the road for adventure on motorcycles and, joined by other enthusiasts, soon gained notoriety as roving packs of dangerous gypsy outlaws who terrorized the highway stretches and small towns of the nation with all-night beer and dope-fueled carousing, brawling, and illicit sex. The subculture took on a decidedly darker tone, with the new breed of bikers incorporating much of the sinister iconography of the military, such as the leather jackets, Nazi-style field caps, and the skull and wings patches of the Air Force, while an event known as the Death’s Head Derby had as its trophy a real human skull. On the carnival circuit, Lucky Lee Lott’s Hell Drivers had dominated the cycle “suicide spectacle” scene (one of Lott’s competitors was in fact called The Suicide Club, complete with skull and crossbones logo). Beginning in 1935, these daredevils drove their machines through brick, metal, and tin walls which were often on fire as well. The riders also collided head-on with speeding cars and jumped their cycles onto flying airplanes. The Hell Drivers began as the Satan’s Pals, painting their cars and cycles the ghostly white of the graveyard save for their moniker in dripping blood-red. By the late 40s, Lott’s Hell Drivers were the largest touring stunt show in America. “Wall of Death. Thrilling. Hell on Wheels. Chills! Spills…” the posters screamed, alongside a cartoon depicting an out of control cyclist about to careen his machine over the bank track and into terrified audience members as the huge head of the Grim Reaper looked on in soul-hungry anticipation. The word “Hell” and the skulls and fiery imagery of the troupe’s carnival posters would be forevermore embedded in biker culture while Lott (whose preference was the Indian Scout) later found work as a stuntman on the prototype biker flick The Wild One and eventually inspired the antics of daredevil Evel Knievel.

By 1946, the American and European cycle industries began to rally from the long financial strain of their commitment to the war effort. After an extended period of inactivity, cycle racing came back to the fore and California became the national hub of the action, with many vets with mechanical training turning their talents and energies toward the state’s booming hot rod and motorcycle speed scenes. With Indian all but dead, the Limeys’ successes at the race track and the number of Brit bike dealerships sprouting up throughout the US continued to plague Harley-Davidson, with Norton and Triumph becoming Harley’s fiercest competitors for coveted California honors. By the early 1950s, Triumph’s string of successes included high profile events like the Daytona 100-Mile Amateur classic, the Catalina Grand Prix, the Jack Pine Enduro, the Laconia 100, and the Riverside and Peoria Tourist Trophies.

In 1947, on the Fourth of July, the two strains of American motorcycle subculture collided. In the small town of Hollister, California, an AMA-sponsored gypsy tour gathering with family-friendly racing and hill-climbs was infiltrated and outnumbered by thousands of motorcycle thugs from disreputable clubs with punk rock names like the Boozefighters, the Galloping Ghosts, the Market Street Commandos, the Pissed Off Bastards, Satan’s Sinners, the Winos, the Yellow Jackets, and the 13 Rebels. Like modern day pirates, the renegade bikers effectively seized the town and predictable chaos ensued. The state police were called in to quell the melee with tear gas, and a similar event in Riverside shortly after proved that Hollister was not an isolated instance. Oddly, the event that launched the mystique of the outlaw biker has been widely disputed. Some gang members who were there claim that nothing of the scale reported by the media ever occurred at Hollister and that even the infamous Life magazine photo of the fat, drunken, and terrifying hoodlum surrounded by beer bottles was a hoax; in fact a paid actor and not even a real biker. Whatever the case, the image stuck and the biker became a drunken antisocial menace to be feared in quiet America’s mind. When the AMA attempted to disassociate itself from the outlaw clubs by claiming the renegades represented perhaps one percent of the riding population, the unsavory bikers quickly added “One Percenter” patches to the skull-on-wings motif of their leather jackets. Motorcycle “gangs” came to symbolize all that the post-war nation sought to repress, a violent youth-gone-wild phenomenon with long greasy hair, Gestapo-like leather outfits, tattoos, and no sense of decency or morality. The Hell’s Angels Motorcycle Club, formerly the Pissed Off Bastards of Hollister infamy, formed in San Bernardino, California in 1948, and a second chapter was soon formed by members of San Francisco’s Market Street Commandos. New Hell’s Angels chapters sprung up around the nation and rival clubs were formed as wild biker rallies and gatherings in places like Daytona and Sturgis became annual institutions.

By 1950, the military- and Viking-inspired leatherwear of the outlaw bands had largely replaced the natty leisure clothes of the average law-abiding citizen biker and leather clothiers were advertising widely in the mainstream biker rags. The outlaw gangs also contributed immensely to the insider’s lexicon of the subculture, adding expressions like prospect, citizen, old lady, tats, ape hangers, colors, and leathers. Just as most initially countercultural trends inevitably enter the mainstream in some palatable form, by the mid-1950s, hip Hollywood actors became the new, sanitized poster boys for the second boom in biker culture. Marlon Brando proudly rode his Triumph Thunderbird and appeared in 1953’s The Wild One as a leather-clad jive-talking delinquent whose gang of misfits shatters the idyll of a small town. The film was inspired by the events at Hollister a few years prior. Co-star Lee Marvin’s characterization of Chino was reported to be based on “Wino” Willy Forkner, the leader of the Boozefighters who had played a vital role in the calamity. The friction between Brit and American bike enthusiasts is authentically represented by that between Brando’s Triumph pack, the Black Rebels Motorcycle Club, and Marvin’s Harley-riding Beetles. (Like Dean, Newman, and McQueen, Lee Marvin was another Hollywood actor who raced competitively as a second career). At the same moment that American audiences were being shocked by The Wild One’s take on their youth culture, a young doctor named Ernesto Guevera left Argentina with a friend for a motorcycle tour of South America and recorded his adventures in what would become The Motorcycle Diaries. The people and conditions Guevera encountered on his travels would lead to the playing out of Castro’s Cuban Revolution a few years later and to “Che” Guevara’s status as America’s enemy number one.

1955 was a banner year for youthful rebellion in the United States. Rock and Roll was all the rage, with subversive new black stars like Johnny Ace, Fats Domino, Little Richard and Chuck Berry assaulting the airwaves with both seductive romantic entreats and diabolical jungle cacophonies, while music companies like Memphis’ Sun Records rushed to repackage the bluesy new sound with appealing white rockabilly hellcats like Johnny Cash and the Tennessee Two, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, Roy Orbison, and Elvis Presley. Elvis Presley proudly rode a Harley-Davidson and dressed like the rockabilly biker he was, even appearing as cover boy for Motorcycle Enthusiast magazine in leather jacket and Nazi-style cap (After his first gold record, the King would buy himself the latest Harley model every year). Allen Ginsberg read his soon to be notorious poem “Howl” for the first time in San Francisco, launching his own controversial celebrity and announcing the birth of the Beat Generation. Brando disciple James Dean’s only three films appeared in the cinema that year coinciding with his untimely death in an auto accident while on his way to the races no less. Although Dean never rode a bike on-screen, he is widely remembered as an icon of biker culture astride his beloved Triumph (so much so that Harley-Davidson has been known to use such images in their promotional materials, even though Dean is in fact riding their British competitor’s machines). In a perverse commentary on the cult of live fast, die young immortality, Dean continued to receive hundreds of fan letters a week from rabid fans that either could not accept the star’s death or felt they could still communicate with him despite it.

In the vacuum of Dean’s untimely death, exploitation distributors raided their vaults and independent film producers like American International Pictures began churning out cheap thrills especially aimed at the new youth cult and filled with monsters, juvenile delinquent gangs, hot rods, and motorcycles, the latter a particular favorite among teen boys with titles like Devil on Wheels (1947, starring Mickey Rooney, no less!), One Way Ticket to Hell (1956), Motorcycle Gang (1957), and Dragstrip Riot (1958). Drive-in movies quickly became a hot new trend among driving-age teenagers, and Fort Worth was no exception, erecting among others the Twin, the Belknap, and Cherry Lane drive-ins within a few years in the middle-fifties. Kids making out in cars while watching films about juvenile delinquents, fast cars and passionate necking were a match-made in heaven. Or elsewhere, if one were or a concerned parent or pastor. By the middle 1950s, virtually every red-blooded boy in America wanted a motorcycle.

In 1957, Jack Kerouac’s book On The Road was published to mixed reviews and instant controversy. An ode to the great American highway, the autobiographical novel detailed the cross-country exploits of its narrator Sal Paradise and his literary friends, thinly disguised versions of William Burroughs, Neal Cassady, Allen Ginsberg and other soon-to-be-famous Beat icons. Bursting with a passion for the unbridled freedom represented by marathon cross-country driving, the book also portrayed a new breed of American youth, a world of starry-eyed poets hedonistically indulging in drink, drugs, “negro” jazz, wild Bohemian parties, and casual sex, eschewing traditional American values in favor of a whimsical, free-wheeling blend of spirituality and self-realization. While fast cars, hoboing, and hitch-hiking were Kerouac’s preferred tools of travel, his portrait of the American road as the setting of subversive fun and adventure added to the allure of outlaw biker culture. As Norman Podhoretz opined in the Partisan Review, Kerouac’s spontaneous prose “embraced homosexuality, jazz, dope addiction, and vagrancy” and was no different than “the young savages in leather jackets who have been running amuck in the last few years with their switch-blades and zip guns.”[viii] In lineage with the rebel image of Brando, Dean, and Presley, the handsome, brooding Kerouac quickly became the new glamorous icon of the open road and representative of youth-gone-wild delinquency. Kerouac’s follow-up to On the Road would feature a character named Japhy Ryder, a motorcycle-riding Zen poet based on his influential friend Gary Snyder.

By the early 1960s the doomed romanticism of the youth cult of hoodlums, hot rods, and motorcycles produced an unlikely subgenre within pop music as well. The “teen death ballad” included radio hits such as Mark Dinning’s “Teen Angel,” the Cavaliers’ “Last Kiss,” Jan & Dean’s “Dead Man’s Curve,” Brigitte Bardot’s “Harley Davidson,” and the Shangri-Las’ “Leader of the Pack,” the latter featuring the roar of a motorcycle as a musical motif within its chorus. In the early 1960s, folksinger Bob Dylan, a devotee of Kerouac, proudly rode his Triumph motorcycle on his ascension to capturing the imagination of a generation and knocking Presley from his throne as America’s most popular youth performer. Dylan’s mysterious cycle wreck in 1966 while at the peak of his career would begin an eight-year reclusive semi-retirement in which he did not perform live and added more intrigue to his legendarily inscrutable persona and mythology; he in fact holed up and recorded the mysterious and collection of arcane Americana known as The Basement Tapes. In 1963, audiences thrilled to real-life motorcycle racer Steve McQueen’s daring two-wheeled WWII exploits in The Great Escape, establishing McQueen as the new Hollywood rebel icon and the movie star equivalent to Dylan’s rock star cool.

The mainstream appeal of Hollywood actors, book-writers, and rock and rollers succeeded in taking some of the menace out of the machine, but bikes had become inextricably associated with rebellion. By the mid-1960s, the image of the biker was back in the dirt, as it became once more associated with marauding black leather bands raping and pillaging their way across the country on a two-lane blacktop high on dope and roadhouse juke music. In 1964, coincidentally the year Philip found himself in the New York underground cinema scene, Kenneth Anger shocked willing art film audiences with Scorpio Rising, a portrait of biker life that unveiled the subculture’s blatant homoerotic and fascist aspects and also linked it’s leather-clad hunks to both Christianity and Satanism, as well as to the legacies of Brando, Dean, and rock and roll. Anger’s film became one of the more widely seen films of the 1960s avant-garde cinema, largely attributable to its unrelenting gaze upon its handsome, buff antiheroes and their machines, a fascination shared by movie-audiences of the time. The same year, clashes between young BSA- and Triumph-riding “Rockers” and scooter-riding “Mods” erupted into full scale gang war and riots in Brighton, England and made news around the globe.

In addition to their general antisocial shenanigans, a 1965 government report revealed the Hell’s Angels as gang rapists of teenage girls, drug traffickers, thieves, and generally violent criminals. As always, writers loved a good outlaw. Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters befriended the Hell’s Angels and Allen Ginsberg wrote an epic poem about them. Embedded “Gonzo” journalist Hunter S. Thompson’s scathing and widely read 1966 expose on the gang did little to dispel the sinister myth. Such a reputation fostered a new American mythology, as well as a slew of low-budget exploitation films (many produced by maverick independent film guru Roger Corman) which reveled in the sex, drugs, and razors lifestyle of the biker menace. 1966’s The Wild Angels (featuring Peter Fonda, Bruce Dern, Diane Ladd, and real members of the Hell’s Angels) was a wildly successful hit that drew on the seedy appeal of predecessors like The Wild One and cemented the reputation of the biker for ages to come, as motorcycle cultural historian Lisa Smedman notes.

The Hell’s Angels didn’t like how The Wild Angels depicted them (After The Wild Angels was released, the Hell’s Angels sued director Roger Corman and American International Pictures for $2 million. They later settled out of court for $2,000.), but the movie-going public did. Anything with “hell” or “angels” in the title was a guaranteed money-maker. Most people wouldn’t want to meet the Hell’s Angels in person, but they were fascinated by seeing them on film.

The biker films of the 1960s also cemented the bond between the Beat Generartion and outlaw motorcycle gangs, with a great number of the films featuring a zany, often beret-sporting “token beatnik” (sometimes portrayed by the spacey, distinctly beat character actor Michael J. Pollard) who entertained the other members of the gang with mad spontaneous free-versifying diatribes. 1969 ironically yielded both a new infamy and the second wave of mainstream acceptance for biker culture in America. The Hell’s Angels made headlines with the slaying of one audience member and the assault of several others (including a member of the Grateful Dead during the band’s set) at a Rolling Stones concert at the Altamont Speedway track outside San Francisco, where the Stones had unwisely hired the outlaw gang as security for the free, overcrowded, and drugged out gig (The Angels were later thwarted in a revenge plot to assassinate Mick Jagger). Meanwhile, the crossover appeal of Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (featuring Corman biker-pic veterans Hopper, Peter Fonda, and Jack Nicholson) moved the biker film genre from the grindhouse and drive-in into the realms of the art house as well as back into mainstream cinemas. Embracing Fonda in his role of anti-heroic, hippy era Captain America, US audiences proved to have an undeniable attraction/ aversion dichotomy when it came to its homegrown Harley-straddling outlaws.

Arising in step with the biker movie genre of the last half of the Sixties (and moving beyond the scope of Philip Norman Fagan’s short life) was the career of the seemingly insane stunt rider Evel Knievel. A former Norton devotee, thief, and general nogoodnik, Knievel was an immensely popular figure by the beginning of the 70s, an American folk hero generating a slew of films, comic books, and toys, as he continually resurrected his broken body into that of a Frankensteinian cyborg held together by reconstruction, sutures, and aluminum as it rallied from comas and blood transfusions. While he was a living legend to countless middle-American families, few mothers encouraged their children to follow in his self-destructive tire marks. The same period saw the ascension of S.E. Hinton in the realm of teen literature. In books like The Outsiders (1967), Rumble Fish (1975) , and Tex (1979), Hinton enacted a bittersweet celebration of the misunderstood lives of poor greaser gangs and motorcycle boys in conflict with upper class youths. Hinton’s thugs were poor, violent, and moral; her “socials” were rich, violent, and mean. Who was to judge?

Back in the mid-1950s, the image of Brando, Dean, and Presley, a collective whom fellow road rebel Jack Kerouac would label “America’s new trinity of love,”[ix] contained the seeds of this same mixture of popular appeal and subversive hoodlum menace that would continue to define the American motorcyclist into the 1970s, when motorcycles were slightly sanitized to become featured stars in television programs like Then Came Bronson, CHiPs and Happy Days. And while the hippies had sidestepped the biker uniform for fashion that reflected more positive vibes, the outlaw biker look and attitude, along with its violence, drug use, and nihilism, was embraced by the British punk rock and heavy metal bands that emerged in the late 1970s. Taking the connections between biker and punk culture to its extreme, apocalyptic bands like the Plasmatics and punk-aesthetic films like Mad Max (1979) seemed to suggest that with the impending nuclear holocaust, the ragged, mohawked biker menace would reclaim his kingship of the lost highway, terrorizing his way back to treacherous power. But by the 1980s, Harley Davidson cycles had become the status symbols of the upper classes, with doctors and lawyers straddling hogs bedecked in faux-outlaw leather chaps and vests. At the same time, biker culture also returned to the Hollywood and rock and roll lifestyles with a vengeance. Bikes became a staple of rock music videos and album covers while cycle enthusiast Mickey Rourke (who portrayed “The Motorcycle Boy” in Francis Ford Coppola’s 1989 adaptation of Hinton’s Rumble Fish) inherited the bad boy mantle of Dean and Brando as the premiere movie star biker thug, even forming a celebrity motorcycle gang with former members of the Sex Pistols and Clash . By the Nineties, motorcycle competitions of all stripes were firmly enmeshed in the widely televised pantheon of “Extreme Sports,” a youthful phenomenon whose heart-pounding spectacles catered to a new generation of sports fans and athletes and included skateboarding, BMX racing, and mixed martial arts fighting. Motorcycles were simply a part of American culturescape and free from the historical social class, aesthetic, and age group stereotypes without ever quite losing their associations with carnival antics, outlaw gangs, and B-movies. Bikes, and the crazy youths who rode them, remain a mainstay of the nostalgic rock and roll lifestyle: Dangerous, antisocial, greasy, smelly, loud, sexy, and cool.

Way cool. In a sense, the biker image was never fully integrated into polite society after Hollister and Brando. Motorcycles were symbols of a subculture, one that would be linked simultaneously to hoodlums and artists. But the societal difference implied by a subculture is always doomed to be embraced by the status quo. It is precisely the bad-boy image of the outlaw motorcyclist that makes it a source of vicarious thrills for the establishment cyclist. Back in the middle-1950s, in Fort Worth, Texas, motorcycles and the crazy kids who rode them still meant something, Even if what they meant was just beginning to be defined and associated with a burgeoning counterculture. Occupying an ill-defined place in American culture between the beatnik/rockabilly present of Hollister/Brando/Dean/Presley and the just-around-the-corner hippy dystopian future of Hell’s Angels/biker flicks/Dylan/McQueen, the greaser and the homegrown good ole boy were largely the same, and cycle sportsmanship as ever was associated with athletic skill and prowess as much as tattoos, leather, and lawlessness.

Fort Worth’s “Motorcycle Row” emerged in the early 1950s as a center of national motorcycle racing and innovation, and Pete Dalio’s Triumph shop was the eye of the hurricane. Dalio’s was an impressive place indeed with a large half moon window exposing the mechanical glories of its showroom to the passersby on East Lancaster and mechanical guru Jack Wilson creating some of the fastest two-wheeled machines in the world in the back shop. In step with the glamour of teen-age rebellion attached to Brando and Dean, Philip Fagan and his cohorts became local legends in the motorcycle scene springing up around the motorcycle shops and drag strips in Fort Worth. And like their more famous heroes, the Fort Worth riders preferred Triumphs, BSAs, and Nortons, to Harleys. The American bikes were simply no match for the Limeys on the racetrack; as Jack Dalio liked to boast, “I’ve still got a crick in my neck from looking back for all those fast Harleys.”[x] Throughout the fifties, shops opened and closed, franchises changed hands, allegiances shifted, competition was rampant, but Dalio-Wilson was a constant. “Racing makes a motorcycle dealership,” Dalio believed. His partner Wilson concurred: “If we didn’t have the fun of racing, I don’t know if I could bear up under the plain ol’ everyday work of running a business!” According to Triumph historian Lindsay Brooke, Jack was the “Texas Triumph maestro…One of the world’s best-known Triumph tuners, Wilson built over 65 speed-record-setting Triumphs between 1955 and 1990, as well as countless winning road-race and dirt-track engines.”[xi]

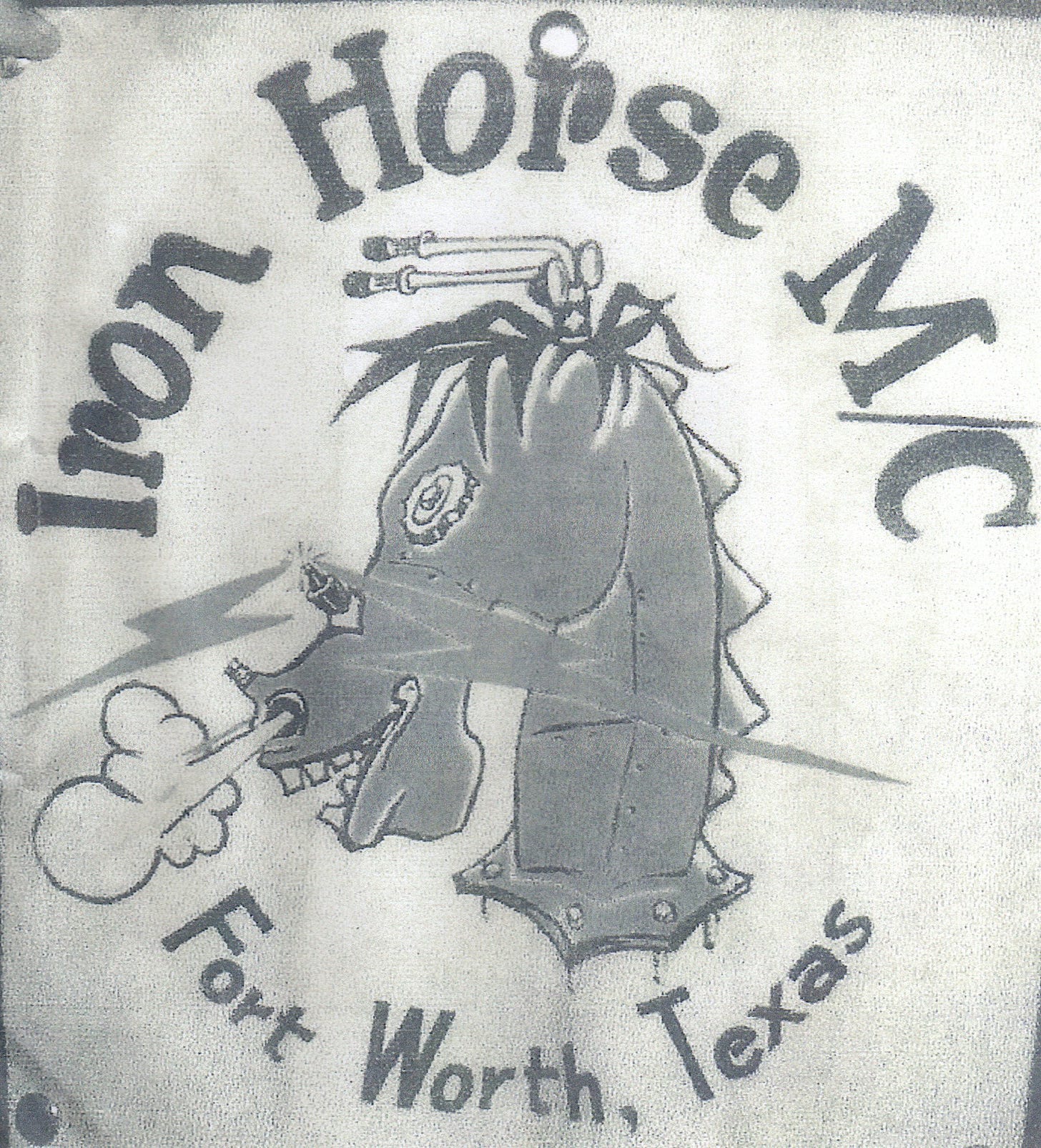

Robert Baucom: Pete Dalio and Jack Wilson are so intertwined that their stories are nearly inseparable. They had a hell of a time getting those Triumphs to beat Harleys but they did it. Dalio’s Triumph shop was at 1509 East Lancaster. I think the Iron Horse Motorcycle Club started there around 1952. Everybody wanted to be a “Dalio Boy.” The Iron Horse clubroom was upstairs in the shop and there was many a poker game played up there. George Fasig sold his BSA shop to Carlton Williamson. Carlton then moved next door to Dalio’s. Fasig then got the franchises for Matchless, AJS and Norton by the Square in downtown Fort Worth. Later he moved his shop on the other side of Carlton. Then they were all right there together on East Lancaster. and it became known as “Motorcycle Row.”[i]

Curtis Terry: Well, it all started back around 19 and 49 with me walking back and forth to school carrying a clarinet that my folks had just bought. And all my friends had motorscooters, and they would pass me and wouldn’t give me a ride. And so I got mad on a Saturday and took my clarinet and got on a bus and went into town; went back to where my folks had bought it, and sold it. Hocked it for twenty bucks. And then walked all over Fort Worth looking for some kind of motorscooter for twenty dollars. I finally found an old worn-out Whizzer at Leonard Brothers Department Store; bought it. Had to get on the bus and go home and tell Mother and Dad that I sold their hundred dollar clarinet for twenty dollars and bought a motorscooter. Mother got very angry and Dad just laughed. Went back Saturday to get it and it wouldn’t run; it smoked and knocked. Dad says, “You don’t want that thing. Let’s go inside and look around.”

Wayne Ellis: Even before I met Carlton, I met Curtis. We’ve known each other since fifteen years old. We go a long way back; he’s a very dear friend. I had a Harley 125 and I’d been working for Western Union on a bicycle, and Curtis was up there on a bicycle, and a lot of my friends on bicycles that had motorcycles later. Back in those days, we didn’t say “bikes” or “cycles.” “Motor-sickles”, that what’s we always called them. Or “motors.” And Curtis, he had a Pal P-81. And then he got a Mustang.

Curtis Terry: At that time, Leonard Brothers Outdoor Store was selling several brands of small motorscooters. One of ‘em happened to be a new model called a Pal, and my dad said “Let’s take that one right there.” And of course it was brand new, chrome fenders, leather saddlebags, two-tone windshield… 55 Chevy V-8 of the day, ‘cuz there wasn’t anything like it around. So I bought that. Dad said “Well, we’ve got to get it home. Can you ride it home?” I had never ridden anything that fast before. So, had to go down the Belknap viaduct, and it was so fast that I scooted my shoes all the way down the Belknap viaduct; I was afraid it would get away from me. And that old Pal taught me a lot. It taught me how to be a mechanic ‘cuz it broke down all the time. So finally along came another brand that Leonards took over called the Mustang. American made motorscooter, made in Glendale, California around 1949. Right in the early part of 50, we took the old Pal back to Leonard Brothers and traded it in on a Mustang. And all the kids started making the switch to Mustangs. And of course, the Mustang, it was as fast as any car on the street at that time. I mean the 50 Oldsmobile and 49 Oldsmobiles were pretty fast, but anything else, the little Mustang was just as quick. It was the thing to have for a kid, you know?

Curtis Terry: So the next thing you know, we’re riding down East First Street, me and a buddy, and something passes us that we’ve never seen before. Two guys talkin’ to each other and they just drifted right on past us, went out of sight. “What was that?!” We found out it was an English bike called a Triumph. So we got to looking around and found out there was a place over on East Lancaster that had just opened up. He was selling Indian motorcycles and Triumph motorcycles. So we beat it over there. And, man, it was just like opening the gates to…to Tomorrowland! So everybody started making the switch to Triumphs and Dalio’s was the place to be. That was where the action was, man. I didn’t know who the president of the United States was, nor the governor of Texas, probably not even the mayor of Fort Worth. But boy, I knew who Pete Dalio and Jack Wilson were!

In the mid-1950s, Ft. Worth had its own version of “Rocker”-type British bike racers, made famous by the Ace Cafe legions back in Merry Olde England. Instead of a cafe hangout, the hub for gathering in Ft. Worth was mainly Dalio’s Triumph Shop, though others might have preferred George Fasig’s Indian dealership (which later became Carlton Williamson’s shop)...Philip Fagan was definitely one of the colorful stars of the Ft. Worth racing scene... ~Bev Bowen, Cowtown cycle scene historian

Wayne Ellis: Boy, I tell you, back in those days when you had Dalio’s and Carlton’s, and George Fasig at the time was down across from the courthouse, and Marvin Bell, and then later Johnny Allen, and all these guys that just sort of came up through the ranks and became dealers; they were all just part of history, y’know? Dalio was there first as far as I remember. Dalio’s was at 1509 east Lancaster which is fifteen blocks from downtown coming down Main Street. I grew up about ten blocks right straight south of Dalio’s. Real rough neighborhood; you wouldn’t even want to go there in the daytime now, much less the nighttime. Pretty rough, a lot of crime. But it was a great neighborhood back then. A lot of my friends grew up there too. I know he was there in 48-49. And he hadn’t taken on Triumphs yet; he was Indians. Then you had Walker Indians which was over in Arlington at the corner of Cooper and Division. Anyway, they were long time friends, Pop Walker and Dalio.

Curtis Terry: Pete used to be across the street in 47 and 8 at a place looks like an old filling station now, but it was a rental place. And he had that 1509 East Lancaster specially built as a motorcycle shop. But for Indians. And he moved in there in 49. And then he had a chance to take on the Triumph franchise. So they had this big competition among the franchises, having Indian on the floor and Triumph on the floor. And so one day Vic Cox came in, he was the representative for Indian, and he said “Pete, we gotta do something here; we can’t have both these franchises. Indian’s been around a long time, y’know…” And Pete says “Why don’t you just load those Indians up and take ‘em. ‘Cuz I’m goin’ with Triumph.” And that was sad, because Pete had made his reputation racing Indian motorcycles. So that was a big leap for him; kind of like these people in the foreign car business these days.

The racing and speed success story of Triumphs in the United States was an anomaly to say the least, as historian Lindsay Brooke describes in his 1996 book Triumph Racing Motorcycles in America.

Triumph never built a great racing motorcycle, at least not by the purist’s definition. There was no pedigreed equivalent of the Norton Manx, Yamaha TZ, Harley XR-750, or MV Agusta. Yet for five straight decades, Triumphs excelled in all forms of American motorcycle sport. From 1938 to 1979, Edward Turner’s original Speed Twin and its descendents won virtually every major U.S. event worth winning, while scoring countless victories in Amateur, Novice, and Sportsman competition. And along the way, they held the outright World Motorcycle Speed Record for 15 straight years. The inherent greatness of Triumphs as racing machines was in their humble production-line heritage, their broad tuning potential, and their versatility. These were motorcycles built in quantity, to a price, and designed for general use. There wasn’t an exotic among them. Even the relatively few purpose-built racing models- the Grand Prix, the close-pitch-fin 500-cc production racers of the late 1950s, and the TT Special- were not inordinately better racing bikes than what Joe Customer could buy in any Triumph showroom and, with modest effort and expense…, convert into viable competitors…Triumphs, particularly the immortal twin-cylinder models, could truly do it all…a near ideal combination of power, balance, and durability- certainly the basis for their TT and cross-country domination for so many years. Few, if any, machines of the period could handle everything from casual trail riding to punishing 500-mile desert races, from two-up touring to National TTs, and instill so much confidence in those who rode them…Hardware was only half of Triumph’s American racing saga, however. The collective heart and soul of the legend were the talented riders and skilled tuners, many of whom are forever linked with the marque…and hundreds of local heroes. [i]

Brooke gives ample credit for the brand’s stateside success from the 1950s on to Fort Worth’s master tuner Jack “Big D” Wilson, even including Wilson’s performance tips for various Triumph models in the book’s appendix. Jack played a major role in the speed-obsessed lives of all the young kids that came to form the Dalio’s-based Iron Horse Motorcycle Club, including Philip Fagan whom Wilson would hire as an apprentice mechanic. Jack Wilson was the king of Triumph tuners and the Fort Worth kids knew they were lucky to have him. He had come to work for Pete Dalio at a decisive moment in the history of Triumph in the US. In 1951, the American Triumph scene split into two distributors, with Triumph Corporation on the East Coast and Johnson Motors on the West. Although TriCor technically had a much greater service population and better markets, JoMo’s territory included all of Texas and California. The result of the split was a whole new arena of competition within the same brand: East Coast Triumph vs. West Coast Triumph. Brooke: “Jack Wilson, who built many world-record-beating Triumph twins in Pete Dalio’s Dallas (sic), Texas, shop, tried to remain neutral in the TriCor-JoMo political battle, even though he was geographically in the latter camp. ‘I respected both sides,’ Wilson noted, ‘but JoMo and TriCor never could get along. Their people were always fighting at Daytona, to the point where they never even shared a garage.’ Wilson noted that whenever TriCor would provide him with racing parts, he was told not to mention it to JoMo.” [ii]

Curtis Terry: Before the (Triumph) Thunderbirds came out, the Speed Twins were the thing to have; that was a 500 cc, like my dad bought me. Well then they came out with a racing version of it called a Tiger 100. Oh my goodness! And Pete was gonna get one. It arrived and they assembled it and they set it back there on the showroom floor waiting for everyone to come by and see it. Like when the Ford Mustang came out. Everyone was just waiting. Good lord, it looked like…First time we’d ever seen a candy orange paintjob on a gas tank. Alloy cylinders. Alloy fenders. Racing megaphones on it. Shined within an inch of its life. Come into the showroom, walk into the shop and there it stood in all its grandeur. They picked a time for people to come and see it, y’know? Well one of those old Indian riders that hung around there, I don’t know where he got it. But he got a…a “number two deposit.” About that long. I don’t know where he got it. And he laid it on the seat of that Triumph. Oh my goodness! (laughs) Pete’s up there in the showroom and he don’t know about it. And everybody walks in and they’re goin’ into hysterics, y’know? “This thing really is a,” whatever four-letter word you wanna use. And we were just in tears. And Pete comes back there and sees that and he explodes! I guarantee you that if he had a gun and he knew who did that, he would have shot ‘em on the spot. But that branded that motorcycle. I guarantee that story lasted us a long time.

Wayne Ellis: Anyway, I was fourteen when I first would go over there on my bicycle. You know, I’d walk in and mess with the motorcycles, and Pete Dalio would tell me not to touch ‘em, “Don’t sit on ‘em!” you know? “Get off that!” And when I’d leave, the guy’d always say “Come back when you got some money!” That’s Dalio, see?

Robert Baucom: I once heard Pete tell a tire kicker, “Well, it’s closing time, Stud. You want to buy this son of a bitch or do you want to talk about it?” Said tire kicker went to his car and got his check book.

Curtis Terry: Pete was kind of a curmudgeon. And Pearl was his enforcer, his wife. And if they didn’t like you, you were not welcome. And they liked me a lot because Daddy was constantly buying a motorcycle from ‘em for me, or parts. My daddy was a prince of a guy, y’know? And Pete loved to dig you. He loved satire. Big time. Oh, he loved it; if he could get something on you, man, you were done for. And one day I showed up over at Dalio’s about 54; I had just got married and bought that new AJS from Carlton, and I walked in: “Oooh…You’re one of Carlton’s boys now? Well you don’t need to be comin’ around here, you little blankety-blank,” you know what I mean? So I said, “Okay you old dago; I don’t have to deal with you.” He picked up a carbureator and acted like he was gonna throw it at me and I told him “Well, if you miss, you’re gonna break out this plate glass window!” So for a while we weren’t on the best of terms around there.

And during the time he didn’t like me, it was wintertime and cold, golly was it cold. And I was working for Western Union on my Mustang, And they would send you out ten or fifteen miles on your Mustang to TCU to deliver a telegram, ice and snow on the ground. That’s how I learned to ride, slidin’ and getting’ back up on it. Pete had in his shop, they’d taken some of that blue tubing they used to use to funnel stuff out through the roof, and they’d welded sections of it up like a figure S, put a gas hose in the end of it, and that thing would warm the shop up, man. The guys would come from outdoors into Pete’s to warm up, and Pete was proud of that stove. Well, me and a fellow named Mitchell Miner, we concocted something to interrupt that. So we went down to the corner where the old hang-out drugstore was, and all the winos hung out; it was a story in its own. And we bought about six Almond Joys, Mounds. So we slipped over to Pete’s and we’re over by the stove warming our hands and everything, and when no one was lookin,’ we tore up all those Mounds and dropped ‘em in the flu of that furnace. And here they go right on down and they start cookin’. Now, I don’t know if you’ve ever smelt chocolate candy burning or not. The smell is terrible! But what’s really bad is the black smoke it gives off. In about five minutes, that place started smelling so sickening that you couldn’t stand it and in another five minutes from about the waist up, you couldn’t tell who you were talkin’ to. It was solid black in that shop from the waist up. And Pete pegged us ‘cuz we were sittin’ up there in the showroom waitin’ for it to happen, you know? He started screaming; they opened all the windows, all the doors, had to shut the whole place down. And it must have been two, three days before they got that sick sweet smell out of there. We didn’t go round there for quite a while, I must say. Because we had a new set of names.

Robert Baucom: Then you had all the young guys like Jimmy Jay and Jess Thomas needling the “old folks,” getting under Pete’s skin every chance they had and loving it. Pete was a long, lanky guy with a long dark face like a death’s head. He had this way of talking with his hand on his hip, like a gay, and he would kind of chop his other hand at you when he talked and repeatedly punctuated his discourse with “Stud.” He called everybody Stud. Tom Ryan mimicked him once until Pete looked at him and asked, “Are you trying to mock me, Stud?” Fagan tried to pull a few jokes on him also.

Jimmy Jay: He was so much fun to pick on. And Jack (Wilson) wasn’t much better: “Cracker ass kids!” I can remember they got the dyno. Now the dyno’s called a water brake and you have to have a source of water. And so they had the dyno shack; it was sitting right outside the back door; they built a roof on it in order to get back there and put those motorcycles on it and see how much horsepower they’d make. Well it was getting to be wintertime and Pete says “Jack, that 55 gallon tank, the drum, that son of a bitch is gonna freeze up some night. We need to put some antifreeze in there so it don’t.” Jack said “That’s a good idea, Pete. But first you gotta take some water out, you know, so that there’ll be room.” Anyway, Jack took the plug out in the back that ran into the alley. And Jack must have gone and bought fifty gallons of antifreeze, I don’t know how many gallons, but he poured them all in the tank. And I walked in the back door and said “Jack, what’s all that green shit runnin’ down the alley?” (laughs). And he’s all “Goddamn!” runnin’ back there to shut it off. Stuff like that was happenin’ everyday.

Jess Thomas: You didn’t get close to Dalio, he was really…I think his dad was a first generation immigrant from Italy, you know, and Dalio had this kind of stand-offish thing…It wasn’t just about money or anything like that; he was just really guarded about his feelings. It kind of came out because he made fun of all of us ‘cuz we were kids hanging on him. He was at least thirty years older than all of us. He was in his fifties when I started hanging around the shop. And Jack was in his late twenties. He moved up from Waco, I think, or one of those little towns down around Waco, and went to work for Pete. It was a really amazing relationship. Jack brought in a lot of customers because of his talent and ability. All the guys from the air base were steady customers and spent a lot of money there.

In competition, the Cub was the dominant lightweight of its era. It won every conceivable form of motorcycle sport- cross-country (Catalina GP and Big Bear Run), endures (500-mile Jack Pine), road races (Daytona, Laconia, and elsewhere), and scrambles. Enclosed in a P-38 aircraft belly-tank shell, the Cub even set speed records at Bonneville salt flats! The Cub truly did it all for a decade…Jack Wilson turned Cubs into mid-13-second, 100-mile-per-hour drag-strip demons.[xv] ~Triumph Racing Motorcycles in America

Curtis Terry: So when I hit (Dalio’s), I got there before Jack Wilson did. ‘Cuz Jack was comin’ up from Waco; he had just gotten out of the service and was workin’ for Roy Stone down there. Roy was a big Mustang dealer down in Waco. He was a big seller. And then he had AJS, and Matchless, and Indian. And Jack was working for him. He had just come out of the military, and he had just met Katie; they were going together, and they would ride up here on the weekends. Because this was where all the action was, all the racing and everything. And so when Roy said things were looking bad, Jack thought he’d come up here and interview with Pete. Roy was just a small operation and Pete’s was where the action was, so he come up here and went to work. I first met Jack Wilson in 1950 when I’d take my Mustang over there when Triumphs were first coming in and I’d say “Jack, what can you do to make this Mustang faster?” And Jack took that Mustang down, big pistons, big porch, big carburetor, exhaust system and all that, mill cylinder head. Boy, that old Mustang was dynamite! I was the fastest kid in town on a Mustang for a little while (laughs). Just before that, they’d come out with a smaller version of the Triumph called a Tiger Cub. Well, by the time Jack Wilson got through with ‘em, hottin’ ‘em up, doing everything he could to ‘em, Mustangs were dead meat. Everybody wanted a Tiger Cub. I was tall enough at that time, just barely sixteen, that Dad said “Well, that’ll be an intermediate step for you; why don’t we just go ahead and get this bigger one.” Oh my goodness! Talk about a rocket ship.

Jess Thomas: I bought my Tiger Cub and started racing scrambles about 54…No, 55, basically between junior high and high school. Bob Stoker was the main guy. He was a few years older than I was. To me, he had the most natural ability of any of the guys that raced for Pete and Jack.

Curtis Terry: Stoker, I got him goin’ on bikes when he moved across the street from me. He went on to be Jack Wilson’s number one rider. I taught the guy to ride a motorcycle and he was so much better than me that I had to go home, y’know? He followed Jack everywhere and rode all Jack’s bikes in the races.

Wayne Ellis: Going back to when I had a Harley 125, I won my first field meet in 1952 and Curtis was my main competition on his Mustang. It was a field meet put on at the old Riverside Race Track, which became the Meadowbrook Drive-in, at Riverside and Lancaster. Dalio was putting it on, Jack Wilson was running it. And so Curtis, in the first or second event, busted his foot peg and injured himself so bad he had to have a kidney removed. I won the field meet. And then Dalio didn’t wanna give me the trophy. It took him like three or four months of me going by on a regular basis; he wouldn’t give it to me. “I don’t know where it is, I don’t know where it is.” Jack Wilson heard me one time getting loud, and he comes out of the back, you know: “What’s going on?” I said, “Well, hell, I’m tryin’ to get my trophy; the one I won one here way back in January.” He looked at Pete and said, “Hell, Pete, give the boy his trophy!” And Pete had it way down under the case hidden and he gave me that trophy (laughs). And I had gotten to know Jack at that field meet. He was such a great guy. Just the way he looked, everything, you know? There was just so many great things about Jack Wilson, I can’t say enough.

Jimmy Jay: BSA came out with a little 250 cc motorcycle and Triumph only had a little 200 cc. And there was a period when Jack quit Pete and worked for Carlton next door. And that was just animosity, because Jack was Dalio’s.

Charles Campbell: I can tell you another story about Jack Wilson. He got mad at Dalio and went over to Carlton Williamson’s BSA shop, which was right next door. Triumph was his thing, but when him and Dalio had that little falling out, he built a BSA over there. We had this hot job we’d been running on nitro, you know. Jack had built up a BSA over there. Kenneth Neistal, a good friend you know, wasn’t close like Fagan and myself, but a good buddy of the Fagans (I wouldn’t know him if I seen him today; Jerry looks about the same). He was a natural on dirt, the guy could do anything on dirt on motorcycles. But he was gonna ride the BSA and I was totally confident. I went to the drag strip on that Triumph with full confidence. We wrapped those things as tight as they’d go, and I can’t even remember what drag strip it was; all I remember is I got a good start and I remember hearing this scream. Neistal was speed shifting the thing and I see this terrified look and he passed me with the thing nearly straight up! It was on nitro see, and he outrun me as far as from here to that window over there, you know, on a BSA. And that’s unheard of! When Neistal come around me, I thought Holy Moses. That’s when I really knew Jack Wilson knew what he was doing. Make a BSA run like a Triumph. But he was a genius with the motors. When I knew he was a genius is when he did what he did with that BSA. You know BSA isn’t even in the same league as a Triumph. Not even close. Jack Wilson built that thing. That shook Dalio; he had (Wilson) back within a week.

Jimmy Jay: The thing about Jack is, your motorcycle might beat his occasionally. But on the average, you’re not going to. And Jack was kind of like Winston Churchill; he wouldn’t admit defeat. There was a reason why. And he did so much, because Jack had no formal education at all. He learned everything by trial and error. When things worked, he couldn’t tell you why they worked. All the stuff we study today and know today, he was learning by hit or miss. Of course, Pete did come with the money.

Wayne Ellis: Jack Wilson is the cement for it all. I don’t care if it’s a BSA, if it’s a Triumph or a Norton. All the English bikes. That was the thing. He was a big cheerleader, supporter, the number one mechanic, the guru, the guy who…I mean, he knew what he was talkin’ about when it comes to English motorcycles. Especially Triumphs. And he put Triumph on the map of course, along with Johnny Allen and Stormy Mangham. You can go almost anywhere in the world, even if it’s a Harley event, even if it’s a Jap bike...If it’s motorcycles, and especially English motorcycles, if you mention Jack Wilson: “Oh, Jack Wilson? You knew Jack Wilson?” It’s unbelievable; it’s just like he’s God. And he didn’t do anything to promote himself. He just was him. Jack was just Jack Wilson, just a good ol’ boy, a country boy, y’know?

Jimmy Jay: And Pete was jealous if you want to know the truth. Pete was just jealous of all the notoriety. Because it was Jack that they took to England when they took the Streamliner over there. They interviewed him and so forth, put it in the museum.

Jess Thomas: Dalio kind of quit racing before he got any good at it. He was in a few nationals and things like that, but Jack, his name was the one that was connected to the fast motorcycles and performance. So he’s the one who got all the glory. And a lot of it was actually after he left Dalio.

Curtis Terry: See, Jack Wilson was our hero. He was four or five years older than us and he did all our work. We’d save and scrimp all week then go over to Dalio’s and have Jack Wilson put a set of flat tappets in our Triumph so we’d be five miles an hour faster. Or buy a big carburetor for it. Not to hurt anyone’s feelings, but Jack Wilson literally made Pete Dalio’s business. He really did. Pete was a name; he had a reputation. And Pete had the building and the business and the funding. And that was basically it. Jack was where it was at. He was an experimenter, a competitor, a perfectionist…Everything you wanted to be when you grew up. Boy, I wanted to be like Jack Wilson. He was our hero, man. And over the years, his innovations literally put Triumph in business. And he got the Bonneville named after him. Because as you know, he took it to Bonneville and set records with the Streamliner and everything. So he’s Mr. Bonneville now. He was where it was at all along the countryside. Innovations like making crank shafts out of solid billet, and stroking engines, and burning nitro, all these kind of things; my goodness! He was Einstein to us, y’know? Us kids, we barely knew where to change the oil on one.

Wayne Ellis: Wilson called me "Knothead." Until I started winning at Caddo, then he changed it to "Champ."

Curtis Terry: Jack couldn’t stand idiots. And Jack had a nickname for everybody. You know, everybody was “Lightnin’” or somethin’ worse, y’know? I don’t know what mine was; it was probably something pretty bad. He either liked you or he didn’t like you, or he’d tolerate you. But if you were one of his guys, you got the fastest stuff. And you had to earn his respect. You did.

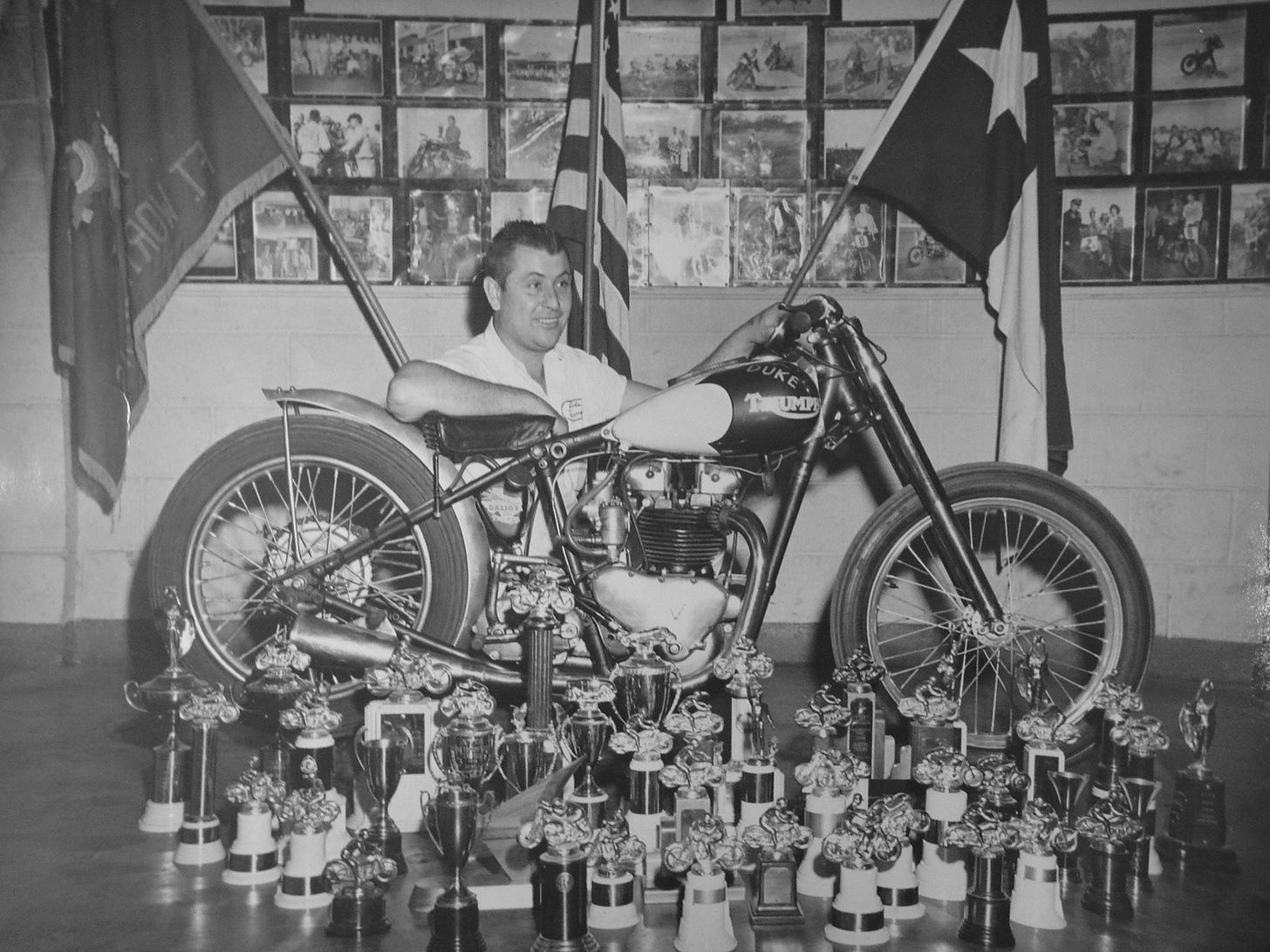

Some bikes attained legendary status, with names like “The Black Widow” and Wayne Ellis’ unbeatable “Dirty Bird.” But Jack Wilson’s ever-evolving pet project, “The Duke” was the most coveted machine of all, with only the most respected riders allowed by Jack to grace its leather throne.

Jess Thomas: Both Philip and I rode this machine (The Duke) fairly often. Out at the road races in the morning and out at the drag strips.

Jimmy Jay: Yeah, Philip got to ride it once or twice.

Curtis Terry: Oh my gosh, it was the one to beat. This was a product of Jack’s innovation. It certainly was, and I mean nobody could beat it. Jack learned to stroke ‘em and he learned to burn fuel. And that was one of the things he pioneered was fuel burners.

Wayne Ellis: I rode The Duke. Man that thing would move…

Jimmy Jay: The trick thing about The Duke, it was the engine. The flywheels were the secret of the thing. There were three sets of flywheels built that were sponsored by Johnson Motors. They were solid billet; they weren’t cast and they made all the difference. And your motorcycle became not a 650 or a forty incher, they became a 50 incher. That was a big secret for years. Nobody ever really beat it. When the thing finally blew up years later when Jess Thomas was riding it out at Green Valley, Jessie was ridin’ that night and they were runnin’ it on fuel and I’ve never seen a motorcycle blow up like this. The entire front end of the motorcycle just hand-grenaded; half the cylinder was just blown out the front. And Pete arrived on the scene, didn’t know what was goin’ on, and he run up to Jack and said “Jack, how’s it runnin’?” Jack was so disgusted and devastated that this had happened that he just pointed at it. “Look, Pete!” and the front cylinder was just all gone. Pete said, “Who was ridin’ it?” “Jessie.” “Well, that figures; that old jinx little son of a bitch!” (laughs) It was always someone else’s fault.

Charles Campbell: This was 55, about the time Harley Sportsters came out. They pulled this motor out of The Duke, this is one of those lay-down dragsters, see? They pulled this motor out, put it in a Full Dress Triumph. Upright handlebars, you know, the ol’ big headlight and shell on it? In other words, brand new. Went out to Yellow Belly drag strip, over in Dallas, this side of Dallas, and that’s the first time I ever rode nitro. And you imagine this dragster motor in a full dress. And Dalio said, “Go back there and warp it a couple of times,” and I went back there in low gear and I remember hitting it and it just whooompp! I was just terrified. He said, “Get on the starting line, put it in second and do not dare use low gear.” And I was so scared; that Harley’s over there, you know. This feeling of relief, when you drop the hammer on it, it just went vvrrrrrrrrrrrrr! It was easier to handle than gasoline because it was just so powerful. Dalio was smart; Jack Wilson built the motors.

Curtis Terry: It was the literally the activity center of the state. The innovation, the beginning of Triumph. You go out on the weekend, watch the races; the English bikes were winning everything! Pete Dalio’s name was big in racing; Pete was a big time racer. And all the racing activities, the dirt track, the half-miles, the Peorias, Santa Fe, all the big ones. Pete had this big truck and he took his Indian racers all around, then he started takin’ Triumphs all around. And so it was the beginning of all this.

About six months later, they came out with a model called the Thunderbird and it was beautiful. Predecessor to the T-110 that came out in about 50 or 51. They were the hottest thing on the street. Well, I couldn’t afford one of them, but Dad said “Okay, I’ll tell you what….” This fella by the name of Marvin Bell that hung around Pete’s had a Speed Twin that he’d souped all up. I didn’t know anything about modifying or anything like that, but Dad went ahead and bought it for me. Dad was always good enough to me to keep me with the latest thing. Boy, it was fast as heck and of course I probably weighed about 98 pounds at the time, so it was competitive for a long time. But everybody started going to those Speed Twins, you know.

You know back then, there weren’t a lot of cars or a lot of people, there wasn’t a lot of television and all these other things. So it was the good times. You know, no crime. No drugs. We’d go downtown to the movies and park our fancy Triumphs out front, don’t lock ‘em or anything. Come back out after the movie was over and they’d still be there. With one exception. One guy’s was just too nice and it had to go! (laughs) Poor old Bob Stoker had the nicest bike in town and somebody stole it. We started lockin’ ‘em after that.

Bob Stoker: My first cycle was a Harley 125, then I had a Matchless, a Pal, then a Mustang. We had a Mustang motorcycle club over at Leonards Brothers Department Store; they let us meet in their parking lot. Then I graduated to Triumphs. Right before the British bikes came in, it was pretty much just Harleys and Indians. Then, Harleys were taboo. It was real clannish. And not just English or American. If you were British bike, you were either BSA, Triumph, Norton…There was competition galore.

Wayne Ellis: Back in the old days, when they only had Triumph, some BSAs and Nortons and Vincents and Harley Davidsons; anybody that rode a Harley was an enemy. Anybody that rode a Triumph, Norton, Vincent, BSA, they all knew each other but they did have divisions. Like the BSAs and Triumphs were always battling each other. Of course, there weren’t any Jap bikes then. In 55, 56, something like that, Pete (Dalio) took on Honda to compete, when they first hit the United States.

Jess Thomas: A lot of guys had Harleys and American bikes in different classes and stuff. But the smaller English engines were in different classes and they were faster than the Harleys. We made fun of Harleys unmercifully. Turned out one of the Harley tuner guys, one of the guys developing fast Harleys over in Dallas, got to be real good friends with us, and he went with us one year to Bonneville as a crew member. Jack (Wilson) was always impressed because he could take a cam shaft and modify it on the bench grinder, stick it back in the engine, and keep fiddling with it till it worked. But we didn’t have much to do with Harleys or the Dallas shops.

Curtis Terry: Marvin Bell at that time was working for Worth Food Market as a butcher. Later on, he did get into the bike business. He was riding Triumphs, you see, and all of a sudden BSAs started comin’ in. So Marvin had a chance to take on a BSA franchise. So he quit Worth Food Market, went out on Belknap midways out by Haltom City, opened up a shop and started selling BSA. And of course that began a friendly relationship, a competitive relationship, between Marvin and Pete. You know, always trying to outrun each other, and then of course, the competition began. And we had this place downtown on Commerce Street, a Harley shop called Helmcamp’s. And they were the scourge. About the 15, 1600 block of Commerce, and that’s where all the Harley guys hung out, and all the motor cops hung out. So if you didn’t ride a Harley, you were a sitting duck as far as the police were concerned. Total harassment, you know? And always the racing part of it, y’know, and as the years went on it just got more intense.

Jess Thomas: Marvin Bell was a long-time BSA dealer. Philip was actually with Marvin for quite a long time as I remember. Actually, after he sold out, (Bell) was involved with Fasig and Norton, at least for (Philip’s 1956 speed record at Bonneville).

Carlton Williamson: See, (Philip) was Marvin’s boy when I came to the scene. And Marvin was a nice, polite, genteel guy.

Curtis Terry: Carlton was living in Corsicana, he was probably fifteen or sixteen at the time. His father had passed away and he was living with his mother. And his mother had bought him a Mustang and he had to ride it to Waco to get it worked on. And that’s where he met Jack Wilson, as a mechanic. And so when Jack moved up here, Carlton naturally came up and discovered the motorcycle business here. Got all excited about it. And we would double date; I guess I knew Carlton before anybody did. He stayed over at one of our good friend’s house over in Haltom City, one of the group, and we all ran around together. So he went back home and told his mother “I want to get in the motorcycle business.” So he bought out Roy Stone’s inventory in Waco, which consisted of Mustang parts, AJS, and Norton parts and the whole motorcycle inventory, and he moved it up here and moved out on Belknap next door to Marvin Bell. And then shortly after, he bought out George Fasig’s inventory, Norton, Vincent, and a bunch of used stuff, and moved it out there. In ’54, when Helen and I were married I had a $600 AJS that I bought from Carlton.