The Passion of the Press

Constructing the Controversy of Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ

Greetings! I hope this Season of Sackcloth and Ashes finds you toning your spiritual and charitable muscles no matter your faith of choice or lack thereof. Can it really be twenty years ago that, amid much controversy, Mel Gibson’s gruesome Gospel film The Passion of the Christ was released, on Ash Wednesday, February 25 2004 to be exact. I wrote the following piece the next year as a graduate student at Northern Illinois University. I felt that enough time had passed at that point to delve into the nature of the furious debate the film had ignited and to examine the media manipulation and management of the controversy it engendered, the flames of which were also stoked by its notorious director, who had not yet at the time of my writing issued his infamous anti-Semitic remarks during a drunken traffic stop.

In the paper chase leading to my MA degree in 2006, I maintained several areas of study as required, but my main focal points were fairly steadfast during the period. I returned again and again to writing about the “Beat Cinema” of the 1950s, the Experimental Underground Films of the 1960s, the heyday of the International Art Cinema from the 1950s to the 70s, and Irish Media and Culture, all while doing rigorous course work, teaching production classes, serving on committees, curating and hosting film series, and producing a feature-length film of my own, all in a new Chicagoland environment while maintaining a new marriage and traveling in Europe for extended periods. Furthermore, the internet was just beginning to walk back then and was in no way the universal database and research tool it has since become. Scholarly research was extremely difficult and time-consuming back in 2005 and often required traveling to faraway libraries even, as those who remember will attest (But at least we were typing on computers by then). I wonder where I got such energy back then and what exactly was motivating me.

Perhaps it was my zealous conversion to Catholicism two years earlier, which likewise led to my fascination with the cultural, ecclesiastical, and spiritual ramifications of Mad Mel’s grisly Jesus film. I was certainly deeply engrossed with contemporary strands of Theological Film Theory and the religious experience and mystical qualities inherent in Cinema. And so, I was turning out unwieldy term papers at the time with titles like “Fractured Messiah: The Challenge to Traditional Representations of Christ in the Postmodern Gospel Drama,” which analyzed films by Pasolini and Scorsese in addition to Gibson’s (some of the ideas from that earlier essay are included in the Passion piece below). I passionately believed there was a “Catholic Cinema” to be defined and discussed, analyzed and appraised, through a pantheon of filmmakers which included Robert Bresson, Francis Ford Coppola, Federico Fellini, Abel Ferrara, John Ford, Werner Herzog, Neil Jordan, Martin Scorsese, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Ken Russell, Jim Sheridan, and Andy Warhol among others (including Protestant fellow travelers like Ingmar Bergman, Stan Brakhage, Carl Theodor Dreyer, Jean-Luc Godard, Paul Schrader, etc. along with Jewish outliers Alejandro Jodorowsky and Stuart Rosenberg, both of whom indisputably and blatantly traded in Catholic imagery and themes in their works).

Looking back at some of my grad school term papers can be a bit cringeworthy due to my strained efforts to articulate heady concepts and ideas I was still grappling with along with the prerequisite opaque academic jargon not known for its clarity or reader-friendly comprehension. That said, I think the following analytical research essay still holds up to a casual read (if clearly demanding some further revision). Or so I hope, and I hope you enjoy it. If nothing else, a dry read for the Season of Dry Bones. Thank you as always for reading.

The Passion of the Press: Constructing the Controversy of Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ

In the beginning was the word. Throughout the year leading up to its dramatic release on Ash Wednesday, 2004, major news sources such as The New York Times began to construct a whirlwind of controversy around Mel Gibson’s upcoming film The Passion of the Christ. The controversy changed form many times until the film’s release, ensuring it a level of notoriety and fashioning its pending release into an historical cinematic event. The consistent press coverage given The Passion during this period served to assure curious would-be audiences that their reactions to the film would be polarized, to say the least. They would either love or hate the film for a variety of subjective reasons which would depend upon how they felt about Gibson, Christianity, Jews, foreign language films, screen violence, etc. The Passion seemed to become a sort of litmus test to determine how many controversies a single film could generate and sustain, and as Gibson carefully if aggressively defended his project at select opportunities, the situation seemed to hint at a mutually beneficial collusion between the outspoken filmmaker and the generally hostile gentlemen and women of the press. A savvy Hollywood player like Gibson certainly knew the adage that the only bad press is no press. In this regard, he certainly found a willing ally in The New York Times. As soon as one scandal grew tiresome, another was seemingly generated in its place by the prestigious paper, creating a circus of scandal around a single unreleased, largely unseen film directed by a peerless Hollywood leading man with a questionable reputation.

As much as has been written about the film, what has failed to be examined is how this controversy was constructed and evolved. Kendall Phillips (1999) has asserted that “controversy” is at best a problematic term due to its sheer pervasiveness (p.488). Essentially, any opposition or argumentation contains within it the seeds of a controversy. Phillips draws on a range of previous scholarship to define “rhetorical controversy” as “those places where arguments and the speech acts forwarding arguments are opposed, the process of public deliberation is problematized, the background consensus is obscured, and the search for common ground is halted” (p.489). What exactly, then, was the nature of the extensive controversy surrounding The Passion of the Christ? How was the frame linking Gibson’s Christ film to terms of controversy fashioned? How was this controversy constructed by key players like Gibson, The Times, the Anti-Defamation League, and the hyperbolic reactions of film critics, religious scholars, and news reporters? If the word “controversy” and its variations are inextricably linked to Gibson’s film, what in fact constitutes such a controversy? Is it even possible that the film’s unprecedented pre-release notoriety was the result of genuine human interest, generated by the objections of certain offended religious groups or weak-stomached film audiences who had not even viewed the film? Or, rather, was this controversy the careful construct of increasingly sensationalistic journalistic practices; an inevitable result of the overwhelming attention news agencies lavished upon an unreleased film that seemed to contain an endless potential for sensationalism, exploitation and scandal? How did Gibson himself work in conjunction with the media to contribute to all this? Most importantly, How did the various reactions to The Passion as reported in The New York Times contribute to the carefully fashioned, ever-morphing dialogue that surrounded the unseen film for a full year before its release?

Fractured Messiahs: Controversy and the Postmodern Christ Film:

The Gospel drama was long considered as safe a film genre as the Western or Gangster film, ensuring audience satisfaction through its own similar set of familiar generic conventions. Defined and confined by the creative restraints implicit within the defining narrative of Western civilization, the conventions of the Gospel Drama were less prone to the instability and revisionism of other film genres. Altering the form of the Gospel Drama meant challenging the New Testament itself and religious controversy was, in the Golden Age of Hollywood, something to be avoided at all costs. Beginning in the turbulent 1960s with Pier Paolo Pasolini’s La Ricotta and The Gospel According to St. Matthew, the Gospel drama, along with other established genres, began to radically shift form. The postmodern era ushered in a new type of religious film with counter-cultural sensibilities and a variety of controversial elements. In 1988, Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ went even further than Pasolini in stirring up a controversy around a largely unseen Gospel film (Fagan, 2005). As Robin Riley meticulously documents in his book Film, Faith and Cultural Conflict (2003), the scandal surrounding this film is perhaps best analyzed in the terms of a rhetoric of scapegoating as delineated in the works of Kenneth Burke and Rene Girard (Riley, p.3). Liberal progressives argued freedom of speech to champion the Scorsese film’s production and release, while conservative Christian representatives sought to ban the film outright, claiming it was a blasphemous violation of their religious rights. Both sides used the occasion of Scorsese’s film to effectively vilify their opponents; each casting the other as the embodiment of society’s ills. Less then twenty years later, another postmodern Christ film would ignite a similar scandal and eclipse The Last Temptation as arguably the most controversial film ever made by a major Hollywood director.

What The New York Times learned from the Last Temptation Scandal:

The scapegoating element surrounding The Passion’s controversy shares much with that of Scorsese’s film. The battle between progressive liberals and the religious right was staged again, but the players’ alliances were now reversed: Conservative Christians unanimously championed the merits of the unseen film and saw it as an unrivaled evangelization tool, while liberal commentators and progressive groups like the ADL sought to defame its supposed anti-Semitism and unprecedented violence.

Perhaps most importantly, the far-ranging scope of the controversy surrounding Gibson’s film was the direct result of major news sources such as The New York Times increasingly adapting the sensationalistic, scandal-mongering practices of the tabloids; sustaining and altering the controversy until finally exhausting it. Previous Christ films like those of Pasolini and Scorsese had taken the once safe and stable Gospel genre and twisted it into something unsettling, controversial and newsworthy, and The New York Times was quick to realize that Gibson’s upcoming self-produced Christ film would not be realized without acquiring some degree of the same notoriety. Due to the director’s unrivaled celebrity, his penchant for screen violence, his recent conversion to fundamental Catholicism, his politically incorrect behavior in recent years, and the non-traditional approach to the subject he was sure to take in emulation of previous postmodern Gospel Dramas, The Times turned to The Passion as a pet project of sorts. Beginning with a lengthy cover story in the Sunday Magazine in March, 2003, The Times began to carefully construct a complex controversy around the film and would contribute to, and maintain relentless coverage of, its various divisive scandals through to its release nearly a year later.

A search conducted through the on-line Ebsco Host Research Database (http://web5.epnet.com) turned up no less than 60 Passion-related news articles published in The Times between March 1, 2003 and February 25, 2004. A similar search on Shrek 2, the box office champion of 2004, yielded only 11 related articles. Additionally, writers and editors at The Times ensured that each new element of the ensuing controversy would be cleverly framed within the context of the film’s supposedly transgressive degree of graphic violence and would take a building-block approach in constructing a seemingly inexhaustible news item out of Gibson’s film.

The paper’s Sunday Magazine for March 3, 2003 contained an article titled “Is the Pope Catholic…Enough?” by Christopher Noxon. The report had an almost schizophrenic quality to it, as Noxon framed the various elements of the ensuing controversy while simultaneously cultivating an air of intrigue more appropriate to a mystery novel or true crime reportage. The article began, “The first sign that something unusual was going on up the hill was the appearance of a fleet of brand-new Volkswagen bugs, lined up on a muddy bluff like a row of oversize Easter eggs” (Noxon, March 3, 2003); hardly an obvious choice to kick off an expose on Gibson, his father, their nontraditional (or ultra-traditional) approach to Catholicism, and the making of The Passion. But Noxon goes on to reveal that the fleet of cars are in the parking lot of a new Catholic Church in the hills near Malibu, California; that the church is unaffiliated with the official Roman faith and conducts its masses in Latin; and that it was heavily funded by an “unnamed individual congregant with ‘tremendous financial viability’” who had given the cars “as gifts to his nieces and nephews.”

Noxon goes on to inform the reader that this shadowy “congregant” is none other than movie star Mel Gibson and that his Catholicism “has never been a secret, and in fact gives him a sort of reverse-exoticism in a town where other stars dabble in (trendier religions).” He goes on to cite a two-year old interview with the actor, in which Mel claimed to attend “an all pre-Vatican II Latin Mass”, and a more recent Italian newspaper report in which Gibson allegedly issued a “‘scathing attack against the Vatican’, calling it a ‘wolf in sheep’s clothing.’” According to Noxon, the actor and his family had left a more liberal Catholic church in protest and invested money in getting a parish off the ground that was in touch with the more arcane, medieval theology they embraced. Noxon himself attended mass at Gibson’s church and found it differed little to the Catholicism he had grown up with until the homily, when the priest proclaimed the “modern church” an evil “whose wickedness will be dealt with on Judgement Day.”

Noxon imbues the actor and his beliefs with DaVinci Code-like intrigue, claiming that Gibson “appears increasingly driven to express a theology only hinted at in his previous work. That theology is a strain of Catholicism rooted in the dictates of a 16th-century papal council and nurtured by a splinter group of conspiracy-minded Catholics, mystics, monarchists and disaffected conservatives- including a seminary dropout and rabble-rousing theologist who also happens to be Mel Gibson’s father... Traditionalists view modern reforms as the work of either foolish liberals or hellbent heretics.”

The writer goes on to paint a vivid portrait of Mel’s father Hutton Gibson as an addled conspiracy theory junkie and crackpot who “holds that all popes going back to John XXIII in the 1950s have been illegitimate—‘anti-popes’” and that Vatican II Church reforms were “a Masonic plot backed by the Jews.” Noxon seems to critique his own novelistic brand of journalism when he offers the commentary that “the intrigue got only murkier and more menacing from there” before exposing Hutton as a Holocaust denier, and by extension, an anti-Semite. “Whether any of this has rubbed off on Hutton’s son Mel is an open question,” he informs the reader.

After indicting both father and son as both anti-Semites and fundamentalist schismatic heretics, Noxon turns his attention to the actor’s current directorial project which is “a graphic depiction of the last 12 hours in the life of Jesus Christ, based on biblical accounts and the writings of two mystic nuns.” Production stills which Noxon has apparently viewed show a Jesus “beaten to a pulp and drenched in blood, fresh from a flagellation.” The film will allegedly have only Aramaic and Latin dialogue and will not be subtitled.

Noxon quotes Gibson at an unspecified “news conference from last September” as saying of his pet project’s detractors, “They think I’m crazy and maybe I am,” again insinuating the apple has probably not fallen far from Hutton’s cracked tree. Further, Noxon quotes from Gibson’s January interview with Bill O’Reilly while interpreting the quote for the reader thus: “(Gibson) suggested that any reporter asking such questions might be part of a plot to undermine his message of salvation.” Gibson’s former producer on Braveheart is also quoted, adding his bit of underhanded support to the director while simultaneously calling his sanity into question: “But he wouldn’t do it if he couldn’t pull it off, at least in his own mind. He’s obviously satisfying some deep personal need in himself.” A Traditionalist Catholic Bishop is also quoted: “To put the weight of his Hollywood celebrity behind the truth that the whole modern church structure is rotten to the core is excellent.” Another Traditionalist official in Texas, claiming to know Gibson personally, stated that the film will “graphically portray the intense suffering of Christ” and is then paraphrased by Noxon as stating that “Most important…the film will lay the blame for the death of Christ where it belongs—which some traditionalists believe means the Jewish authorities who presided over his trial and delivered him to the Romans to be crucified.”

The final quote is reserved for Mel Gibson himself and his response to O’Reilly’s query as to whether the film will be upsetting to Jews: “It might be…It’s not meant to. I think its meant to just tell the truth.”

Noxon skillfully ties together various strands to construct what would soon become the controversy of The Passion of the Christ. A single story trading in very questionable journalistic practices had synthesized its various components from the beginning: The film’s archaic foreign language dialogue, the dialogue of anti-Semitism and weird sectarianism, the paranoia and egoism of the film’s creator, and the excess of screen violence. Using sound bites from a variety of sources and time frames, hearsay, questionable sources, unverified “facts,” and selectively paraphrasing quotes to serve the purposes of his expose, Noxon effectively wrote a story that traded in the very conspiracy theories, mystery and shadowy intrigue he attributes to, and uses to both discredit and vilify, both Gibson and his octogenarian father. There did indeed seem to be a conspiracy theory at work here, but one of Noxon’s and The Times’ own creation. Noxon tellingly asks his reader a question he has already answered himself on behalf of his paper: “Remember The Last Temptation of Christ?” Indeed, The Times remembered such newsworthy scandals all too well and had already succeeded in launching a similar one to further fuel the culture wars and give the punters what they wanted: Outrage, controversy, scandal.

Holy Wars: The Dialogues of Sectarianism and Anti-Semitism:

From that first lengthy article, The Times laid out a blueprint of the course the controversy would run: The graphic violence, the Aramaic and Latin dialogue, but mostly the religious controversy the film was sure to spawn. Unlike the controversy surrounding Scorsese’s film, which pitted right-wing Christians against liberal progressives, The Passion’s supporters and opponents would not be so clearly defined. Much of the article was devoted to Gibson’s father and his extreme fundamental Catholicism and dissent against the established Roman Church. Would Gibson’s film, then, offend Catholics and Protestants alike? As the controversy unfolded, Gibson’s hardcore Catholic vision would, oddly enough, find its greatest champions in the Evangelical Christian community; meanwhile Gibson consistently defended his film’s violence as being inextricable from his Catholic faith. But many Christians agreed with the secular press that the film’s violence was over the top and threatened to sully or negate the spirit of the Gospels. The article also predicted Gibson’s clash with the ADL and other members of the Jewish community with its intimations of anti-Semitic content in the script. This highly publicized skirmish would become one of the defining features of the controversy, and the ensuing dialogue between Christian and Jewish thinkers at times recalled the scapegoating rhetoric surrounding The Last Temptation.

On August 2, 2003, The Times featured as its cover story an article by Laurie Goodstein entitled “Months before Debut, Movie on Death of Jesus Causes Stir.” Goodstein’s piece detailed the controversy of anti-Semitism that had gathered around the unreleased film in the months since Noxon’s article: “Detractors, who have read the script but not seen the film, say it is a modern version of the medieval Passion plays that portrayed Jews as ‘Christ Killers’ and stoked anti-Jewish violence.” Goodstein cleverly works the other themes from Noxon’s expose into her article, stating that the use of Aramaic and Latin is historically inaccurate “because the Romans spoke Greek”, that the film is “brutally graphic”, and that Gibson is part of “splinter Catholic group that rejects the modern papacy and the reforms of the Second Vatican Council.”

“Mr. Gibson has been screening ‘The Passion’ for a few weeks for friendly audiences, but has refused to show it to his critics, including members of Jewish groups and biblical scholars…A group of Bible scholars who read a version of the script said it was not true to scripture or Catholic teaching and that it badly twisted Jewish leaders’ role in Jesus’ death.” She goes on to paint a new conspiracy theory of an Ad-Hoc group of Catholic and Jewish/ ADL interfaith scholars who approached Icon, Gibson’s production company, with a request to review the script for anti-Semitic content. Gibson had supposedly “set off alarms” among the group when it was reported that the script had been inspired by “the diaries of Sister Anne Catherine Emmerich, a 19th-century mystic whose visions included extrabiblical details like having the Jewish high priest order Jesus’ cross to be built in a Jewish temple.” Icon failed to respond to the request, Goodstein reported, but somehow the script still managed to innocently find its way into the scholars’ hands. They sent their concerns to Icon after finding much that was troubling within it. When they again received no response, they opted to go public- Through The New York Times, apparently. Icon and the Ad-Hoc group each claimed the other had leaked the scandalous story to the press. Gibson attempted to reconcile with the Catholic representatives of the group, but not its ADL members. Abraham Foxman, national director for the ADL lamented, “If you say this is not anti-Semitic and this is a work of love and reconciliation, why are you afraid to show it to us?” Gibson’s representative at Icon responded that there was no way any of “those people” would be invited to a screening. They had discredited themselves in the eyes of the film’s production company and were “dishonorable”. Of the controversy, Gibson also tellingly added, “You can’t buy that kind of publicity.”

The following day , The Times’ Frank Rich weighed in with his appraisal of the situation titled “Mel Gibson’s Martyrdom Complex.”(August 3, 2003). This would be the first of Rich’s scathing attacks on the unseen film and Gibson personally. “These days, American Jews don’t have to fret much about the charge of deicide—or didn’t until Mel Gibson started directing a privately financed movie called ‘The Passion’…Why worry now? The star himself has invited us to.” Rich follows with the same sound bite from the O’Reilly Factor interview that Noxon had previously used to similar effect. He also links Gibson’s supposed refutation of Vatican II as a blatant rejection of reforms that cleared Jews of deicide and rails against the anti-Semitic elements in the writings of Emmerich, including her alleged revelation that “Jews had strangled Christian children to procure their blood.” Rich also expressed the fear that the film would intensify violence against Jews abroad “where Mr. Gibson is arguably more of an icon,” and attacked Gibson’s previews for select audiences of evangelical Christians (and a single “token Jew”) in which the viewers were asked to sign a confidentiality agreement. “If ‘The Passion’ is kosher,” Rich argued, why weren’t Jews allowed to screen it as well? He goes on to give voice to Foxman’s complaints that Gibson had pre-selected his supporters. It is difficult to fault Gibson here, having made a film specifically for the Christian market and having become the target for Jewish and liberal progressive representatives due to the leaking of an early draft of the script. Icon’s press secretary defended the director by stating that the ADL were banned from screenings due to going public with their concerns prematurely. “Eventually,” Rich writes, “Mr. Gibson’s film will have to face audiences he doesn’t cherry-pick.” Rich accuses Gibson of playing the victim, a lone man of faith defending himself against a secular and/or Jewish “entertainment elite.” “The star’s pre-emptive strategy is to portray contemporary Jews as crucifying Mel Gibson.” Using a careful blend of paraphrase and quote, Rich asserts that the National Association of Evangelicals had intimated that the Jewish assault on The Passion could cost Israel the support of “two billion Christians.” However, it might be argued that the over-the-top histrionics of Foxman, Rich, and other self-identified Jewish opponents of the film did more in the press to fuel Jewish stereotypes than any film Mel Gibson could produce.

In another episode cloaked in shadowy intrigue just a month before the film’s release, Foxman and another Jewish leader sneaked into one of the exclusive screenings of the film and went straight to The Times with their impressions. To little surprise, they found Gibson’s film “anti-Semitic and incendiary in the way it depicted the role of Jews in Jesus’ death” (Kennedy, January 23, 2003). Foxman declared that the film would fan anti-Semitism and would “set back the dialogue between Christians and Jews by decades,” while Rabbi Marvin Hier was “horrified,” stating that Jews were portrayed “as villainous, with dark beards and eyes, “like Rasputin.” Kennedy also linked Gibson’s pre-Vatican II traditionalism to a denial of Jews being cleared of the centuries-old charge of deicide by the official Roman church. Another Jewish leader who, despite The Times’ repeated insistence on a “Jewish ban” at screenings, had seen the film twice, was upset that a controversial bit of dialogue spoken by one of the Jewish priests (“His blood be on us and our children”) had been reinserted into the latest screener. “He said even the most noxious Passion plays omit that verse, which he called ‘the religious taproot for what has become the blood libel, and collective guilt and the charge of deicide against Jews.’” Foxman claimed to have initially felt bad about infiltrating the screening, but then decided it was his “moral duty to see it.” While avoiding the issue of whether he had signed his name or forged a signature on the confidentiality agreement, he noted that the form stated that only negative discourse about the film was forbidden, and that “pastors and church leaders are free to speak out in support of the movie.”

On February 4, 2004, Times writer Sharon Waxman reported that Gibson had decided to delete the offending scene from the film. This was apparently in response to a letter from Foxman pleading with the director to add an addendum to his film asking its viewers to not allow The Passion to inspire hatred. Gibson sent back a non-commital reply encouraging “love for each other despite our differences” which did little to placate the ADL leader. Waxman had viewed the film earlier in the week and expressed sympathy for Foxman’s cause. She goes on to cite a Readers Digest interview in which Gibson was grilled yet again about his father’s alleged denial of the Holocaust. While Gibson admitted the reality of the attempted genocide and claimed to have friends “who have numbers on their arms” and are “Holocaust survivors,” he was apparently determined to not give the ADL or the liberal press exactly what it wanted at this stage of the game. Rabbi Hier wrote an angry letter to Gibson in response, stating, “We are not engaging in competitive martyrdom…To describe Jewish suffering during the Holocaust as ‘some of them were Jews in concentration camps’ is an afterthought that feeds right into the hands of holocaust deniers and revisionists.” Gibson’s publicist intervened in the newest confrontation: “There’s no doubt in my mind that not only does he know the Holocaust happened and acknowledge it, he has shed tears over it.” Foxman commented that Gibson’s remark was “ignorant” and “insensitive” and that the director simply did not “get that.”

The coverage in The Times also used The Passion to explore sectarianism among the Christian population. Again, the paper’s integrity was called into question when it reported that Pope John Paul II had viewed the film at the Vatican and found it “accurate” on December 20, 2003 (The Associated Press). The brief news report predictably noted that “Some Jewish leaders have said that the film suggests that Jews were responsible for Jesus’ death” and thereby indirectly linked the ailing Pontiff with anti-Semitism. On January 20, 2003, Frank Bruni of The Times covered a report from the Vatican’s news service, which refuted the former claim, although admitting “The New York Times (had previously) quoted unnamed Vatican officials confirming (the Pope’s) remark.” Again, it appeared as though the scandal was too often generated by hearsay, fraudulent reporting, and conspiracy theory. Bruni’s follow-up in The Times’ Vatican Journal section on January 23 offered up a “fizz of theories” as to the misreporting of the Pope’s endorsement, indirectly placing the blame on a Vatican governed by an aging pontiff where “nobody’s in charge.”

Frank Rich weighed in on January 18, 2004 with his article “The Pope’s Thumbs Up for Gibson’s ‘Passion.’” He predictably shifted the blame from the Vatican to Gibson: “Why should (the Pope’s) suffering deter a Hollywood producer from roping him into a publicity campaign to sell a movie?…The ailing pontiff has been recruited, however unwittingly, to help hawk ‘The Passion of the Christ’…That a movie star would fan these culture wars for dollars is perhaps no surprise, but it demeans the Pope to be drafted into that scheme.” Rich quickly reverts to his charges of anti-Semitism, citing a variety of Christian and secular sources who had found the film’s depiction of Jews disturbing. He finds “the marketing of this film…a masterpiece of ugliness typical of our cultural moment…Mr. Gibson and his supporters have tried to slur the religiosity of anyone who might dissent…(and have) accused modern secular Judaism’ of wanting ‘to blame the holocaust on the Catholic Church.’”

On February 5, 2004, Laurie Goodstein reported on the use of the film as an evangelism tool and the gleeful zeal in which Born-Again Christians were embracing the radically Catholic film’s selected screenings. “Catholic clergy,” however, “have not latched onto it as a tool for church-building as the evangelicals have.” Goodstein also reported on the wide array of merchandise being toted out with the help of Christian marketing firms for the film’s pending official release. Again, the film’s overwhelming violence and its potential threat to “provoke animosity toward Jews” was referenced, along with Gibson’s supposed claim that “on the movie set, he witnessed agnostics and Muslims converting to Christianity.”

The day before the film’s official release, James Barron penned an article for The Times recounting the varied reactions of Christians at a church-sponsored screening (February 24, 2004). Neither the preview audience nor Barron’s readers needed his reminder that the film had been “a subject of debate in religious circles for months because of concerns about its graphic violence and its portrayal of Jews in events leading to the crucifixion.” The piece was essentially a “non-story,” evidence that The Times would produce news about the film whether there was actual news or not.

St. Mel, Martyr: Gibson Stars as The Willing Victim:

Gibson’s own contribution to his film’s notoriety cannot be overstated. Throughout the course of the controversy, the director granted interviews and issued several controversial public statements. He consistently resisted opportunities to emphatically deny that his film was anti-Semitic; he played up both this angle and his graphic depiction of a suffering Jesus as the result of a firm religious understanding and conviction, and generally managed to generate more scandal every time he defended his project. He attacked his dissenters in an openly hostile manner and even threatened to feed one journalist’s entrails to his dog. Far from trying to quell the rising tide of controversy, Gibson seized every opportunity to enhance it or take it in a completely new direction. While Gibson found few supporters at papers like The New York Times, he effectively worked with them to construct the cultural phenomenon of the film’s controversy.

In Frank Rich’s first scathing attack on Gibson (August 3, 2003), the author made the relevant point that the director had defended his project to both to Bill O’Reilly (on January 14) and The Wall Street Journal (on March 7) against “any Jewish people” attacking it. Rich points out that this was before anyone had even publicly acknowledged the film’s production, much less criticized it. However, Noxon’s article had appeared on March 3. When Rich requested to see the film, Gibson’s publicist explained that The Times remained a “low priority” due to Noxon’s “inaccurate representation” of Hutton Gibson (Rich, August 3, 2003). Gibson could have certainly curtailed some of Rich’s and The Times’ hostility by acquiescing to their requests for screenings and interviews.

An article by Peter J. Boyer in The New Yorker on September 15, 2003 upped the ante on the rhetoric of war between Gibson and his Times critics, and also called the paper’s journalistic practices into question. Boyer points out that Gibson and his film have “been unfairly associated with the eccentric views of Gibson’s father, who in a New York Times column was accused of being a ‘Holocaust denier.’” He goes on to question the paper’s journalistic integrity by stating that The Times had put the number of Traditionalists at “a hundred thousand, but other estimates vary widely.”

Boyer further indicts The Times for its part in creating a full-blown scandal around the unseen film: “That ‘The Passion’ became the subject of such contention a year before its planned release, however, was an accident—not of politics, or even religion, but of real estate.” According to Boyer, Noxon was the son of a homeowner in the neighborhood of Gibson’s new church who opposed the zoning laws that had worked in Gibson’s favor. Noxon then went on to shape a creative story based on three key points: Gibson’s radical retrograde brand of Catholicism, his father’s influence on him in this regard coupled with Hutton’s supposed anti-Semitism, and the inevitability that his Christ film would be a “propaganda vehicle for such views.” Boyer also credits Noxon’s expose with being the catalyst for the action of the Ad-Hoc scholars group.

Gibson was given a perfect vehicle by The New Yorker to play the victim and lash out at The Times. Boyer arrives to interview him “the day after the New York Times carried a front-page article on the dispute (involving the Ad-Hoc scholars),” most likely a reference to Goodstein’s August 2 cover story. But Gibson is most upset by Frank Rich’s blistering attack on August 3. Gibson says of Rich: “I want to kill him…I want his intestines on a stick…I want to kill his dog.” Gibson goes on to label The Times “an anti-Christian publication,” and notes that he has received a book from an evangelist friend called “Journalistic Fraud: How the New York Times Distorts the News and Why It Can No Longer Be Trusted.” Gibson is apparently cheered by the gift.

As The New Yorker piece clearly demonstrates, Gibson was anything but reticent about his feelings concerning The Times coverage. Rich issued another assault in the form of a rebuttal titled “The Greatest Story Ever Sold” (September 21, 2003). He accused Gibson of being a Hollywood debutante unable to handle criticism that might prick his “bubble of fabulousness,” then rehashes his issues with the star within the frame of Gibson’s supposed conspiracy-obsessive martyrdom complex as gleaned from Boyer’s article: “Who is this bloodthirsty ‘they’ threatening to martyr our fearless hero? Could it be the same mob that killed Jesus? Funny, but as far as I can determine, the only death threat that’s been made in conjunction with ‘The Passion’ is Mr. Gibson’s against me.”

Rich acknowledges that he has “been skillfully roped into his remarkably successful p.r. juggernaut” and that, unlike Bill O’Reilly, he is at least not getting paid by Gibson for his “cameo role.” He goes on to practice the same conspiracy-theorizing he finds so abhorrent in the Gibsons, claiming that The Passion’s website intentionally changes the names of its Jewish opponents to render them more obviously Semitic (“Sulzberger to ‘Schultzberger’) and finally seems to conclude that Gibson’s past “gay-bashing” and all the other evidence points to a plot between Gibson and the administration of President George W. Bush. Whatever attempt Rich had made to correct the impression of The Times Boyer had left with his New Yorker readers, the situation was beginning to resemble a name-calling conspiracy war between two raving and paranoid individuals.

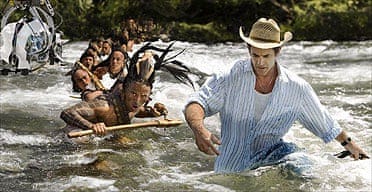

Less than three weeks before the film’s official release, Times film critic Elvis Mitchell suggested that Gibson had been playing the victim saint his whole Hollywood career. In his article “Mel Gibson’s Longstanding Movie Martyr Complex” (February 8, 2004), Mitchell painted a vivid portrait of the actor’s masochistic screen image: “Eyes often misted over with anguish and sorrow, Mr. Gibson has been martyred on screen more often and more photogenically than anyone since Joan Crawford.” Gibson was unparalleled in his “taste for sacrificial iconography” and had “endured the tortures of the damned” on screen: “Mr. Gibson’s stage blood has been spilled on backlots all over the world. He has shown a heartstopping aptitude for- and interest in- the portraiture of the martyr. His taking on ‘The Passion of the Christ’ was, as the old song goes, only a matter of time.”

As of three days before its release, The Times had still not been granted an interview with Mel Gibson for obvious reasons going back almost a year. With no new spin to put on the controversy, Kari Haskell (February 22, 2004) assembled a collection of Gibson’s more notorious soundbites from a variety of other sources, flippantly explaining that he “hasn’t made any apologies for himself, his movie or his father. But he has weighed in on several points. Here are some excerpts.” The headings for Gibson’s dozen blurbs included “Justification”; “On the Film’s Brutality”; “Anti-Semitism”; “The Holocaust”; and “The Critics.” The collection was definitely The Times at its worst, being indistinguishable from the recycled fodder of gossip rags like People magazine. The paper seemed to be grasping at straws in order to keep the controversy going till the bitter end, and the film’s “besieged” director was poised to laugh all the way to the bank.

Conclusion:

The Passion of the Christ officially opened on February 25, 2004. The New York Times featured three full-length stories on the film that day (Scott; Goodstein; Woodward), and three more the following day (Dowd; Goodstein; Waxman; February 26, 2004). The film was still the subject of full-length articles in the paper as late as March 15, 2004 (Waxman), and was trotted out again as hot news during the Holy Week (Thompson, April 12, 2004), well over a year after Noxon’s trend-setting expose on the quirky Gibson clan.

Among The New York Times staff, A.O. Scott seemed to be the most astute and unbiased observer of the controversy swirling around Gibson’s film for well over a year. His article “Enraged Filmgoers: The Wages of Faith” (January 30, 2004) hinted at the contribution his paper had played in generating a multitude of scandals around The Passion by placing it in historical perspective. He compares the controversy surrounding Pasolini’s and Scorsese’s films with that of Gibson’s:

‘The Passion of the Christ’ has brought with it a controversy that seems, at least on first glance, familiar, even ritualistic. Once again a filmmaker has brought his interpretation of Scripture to the screen and once again, before most audiences have had a chance to see the picture, there are expressions of outrage, accusations of bigotry and bad taste and an outpouring of contentious publicity…The sides have reversed. The conservative Christians who were so vocal in their condemnation of…Mr.Scorsese are now equally vocal in their defense of Mr. Gibson.

Furthermore, Scott sees this reversal as a

…testimony both to the endlessness of the culture wars and to the changed landscape of battle. Those Catholics and evangelical Protestants who felt alienated from much of American commercial culture and who informed the earlier protests, have not only a powerful and glamorous Hollywood ally in Mr. Gibson but also a growing sense of cultural and political confidence…We take for granted these days that anything- especially any visual representation- touching on the hard scriptural and historical substance of faith will generate fierce argument…Movies that delve into the Bible or that explicitly offer up interpretations of its teachings and stories can always expect, and easily be accused of provoking, the most divisive and virulent forms of controversy .

Scott places Gibson’s film in a realist and modernist trajectory of films about the life of Christ, and a natural heir to the works of Pasolini and Scorsese, but also notes key differences in the controversy surrounding the newest postmodern Gospel drama:

‘Can we finally look at The Last Temptation of Christ?’ the film critic David Ehrenstein wonders in his liner notes to the Criterion reissue…Political pressures made it difficult for Mr. Scorsese to finance his movie, and the timidity of the theatrical exhibitors meant he had a hard time showing it, problems that Mr. Gibson, for all his public protestations of victimhood, has not had to face, since he made ‘The Passion’ entirely with his own money. And, curiously, attempts to prevent people from seeing it have come from the filmmaker himself, who has held screenings for handpicked, presumably sympathetic audiences and kept out potential critics. All of which will be moot by Feb.25, when we can finally look at ‘The Passion of the Christ’ for what it is- part of a long and tangled movie tradition as well as an act of cultural provocation. The argument about the film’s political implications is important and, in any case, will be hard- at least for a while- to drown out. But at a certain point, disciples of cinema, whatever their other loyalties and affiliations, must reaffirm a basic creed: for God’s sake, shut up and watch the movie.

The various scandals surrounding the pending release of The Passion of the Christ ensured that the film would become arguably the most controversial mainstream film of all time. This was due to various objections to the film’s content, the nature and scope of the film’s pre-release press coverage, and the radical vision and public statements of its famous director during this time period. While many moviegoers refused to see the film for a variety of reasons, the controversy was all but inescapable, maintaining consistent press coverage from almost a year prior to its release to several months after. It became one of the defining cultural, political and artistic phenomenon of the new millennium, providing a valuable blueprint as to how a controversial film is constructed and sustained by the press in the current era of mass media communications.

References:

ADL and Mel Gibson’s “The passion of the Christ” frequently asked questions. (2003, August). ADL On-line. Retrieved September 7, 2004, from http://www.adl.org/interfaith/gibson_qa.asp.

ADL concerned Mel Gibson’s ‘Passion’ could fuel anti-Semitism if revealed in present form. (2003, August). ADL On-line. Retrieved September 7, 2004 from http://www.adl.org/presrele/ASUS12/42.

Adato, A. (2004, March 8). The gospel of Mel. People, 61, 82-89.

Aitken, J. (2004, April). Lenten Gibson. American Spectator, 37, 42-44.

Armstrong, C. (2004, March). The fountain fill’d with blood. Christianity Today, 48, 42-44.

Associated Press. (2003, December 20). Pope said to find ‘Passion’ accurate. The New York Times. Retrieved October 25, 2005 from www.nytimes.com

Barbee, D. (2004, February 15). ‘Passion’ spotlights religious differences. Fort Worth Star-Telegram, pp. 1A, 13A.

Beeson, P. (2004, February 26) ‘The passion of the Christ” or “Jesus chainsaw massacre”. Dateline Alabama. Retrieved March 15, 2004, from http://www.datelinealabama.com /article/2004/02/26/5422_arts_art.php3

Bini, A. (Producer) & Pasolini, P. P. (Writer/Director). (1965). The gospel according to St. Matthew [Motion Picture]. Italy: Titanus Productions.

Boyer, J. (2003, September 15). “The Jesus war.” The New Yorker. Retrieved October 25, 2004 from www.freerepublic.com

Bowman, J. (2004, April). Why not Be anti-semiotic? American Spectator, 37, 56-57.

Chattaway, P.T. (2004, March). Lethal suffering. Christianity Today, 48, 36-37.

Craven, J. & Maltby, R. (1995). Hollywood cinema. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Corliss, R. & Israely, J. (2003, January 27). The passion of Mel Gibson: His Jesus film is bloody, bold…and in Aramaic. Time, 161, p.54.

Cruz, A.M. (2004, March 8). Passion’s play. People, 61, 82.

Cunningham, P.A. (2004, April 5). A dangerous fiction: “The passion of the Christ” and Post-conciliar Catholic teaching. America, 190, 8-11.

Dart, J. (2004, February 24). Passion, Judas present contrast in Jesus films. Christian Century, 121, 15-16.

Davey, B., Gibson, M. & McEveety, S. (Producers). (2004). The passion of the Christ [Motion picture]. United States: Icon Productions & Newmarket Films.

De Fina, B. (Producer), & Scorsese, M. (Director). (1988). The last temptation of Christ [Motion picture]. United States: Universal Pictures.

Denby, D. (2004, March 1). Nailed. The New Yorker. Retrieved March 15, 2004 from http://www.newyorker.com

Donohue, J.W. (2004, April). Of many things. America, 190, 2.

Dowd, M. (2004, February 26). Stations of the crass. New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2004 from http://www.nytimes.com

Ebert, R. (2004, February 24). The passion of the Christ. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved March 5, 2004 from http://suntimes .com

Edelstein, D. (2004, February 24). Jesus H. Christ The passion, Mel Gibson’s bloody mess. Slate. Retrieved March 15, 2004 from http://slate.msn.com/toolbar.aspx?action=print&id=2096025

Emmerich, A. C. (1983). The dolorous passion of our lord Jesus Christ. Rockford, IL: Tan Books and Publishers, Inc.

Edwords, F. (2004, May-June). A dispassionate appraisal. Humanist, 64, 40-42.

Fagan, P.R. (2005). Fractured messiah: The challenge to traditional representations of Christ in the postmodern gospel drama. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Fisher, E.J. (2004, April 5). After the maelstrom. America, 190, 12-14.

Foer, F. (2004, February 8) ‘The Passion’s’ precedent: The most watched film ever? New York Times. Retrieved April 20, 2004 from http://www.nytimes.com

Fraser, P. (1998). Images of The passion. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

Gibson, M. (2004, February). Pain and passion. Interviewed by Diane Sawyer. ABC News.Com. Retrieved September 7, 2004 from http://abcnews.go.com/sections/primetime/entertainment/mel_gibsonpassion.040216html.

Goodstein, L. (2003, August 12). Months before debut, movie on death of Jesus causes stir. New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2004 from http://www.nytimes.com

Gleiberman, O. & Schwarzbaum, L. (2004, March 5). Faith healer? Entertainment Weekly, 754, 46-48.

Grace, P. (2004, Summer). Sacred savagery- The passion of the Christ. Cineaste, 29, 13-17.

Grigg, N. (2004, April 5). Orchestrated Outrage. The New American, 20, 23-28.

Haskell, K. (2004, February 22). The passion of Mel Gibson. New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2004 from http://www.nytimes.com

Jenkins, J.B. (April 26, 2004). Mel Gibson: Passionate art from the gut. Time, 163, 120.

Jensen, J. (2004, February 20). The agony and the ecstasy. Entertainment Weekly, 752, 18-22.

Jensen, P. (2004, March). The good news about God’s wrath. Christianity Today, 48, 45-47.

Kelly, C. (2004, February 27). Crossing the line. Startime. Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 5-7.

Kennedy, R. (2004, February 28). Agreed: All the publicity is a triumph for ‘Passion”. New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2004 from http://www.nytimes.com

Klawans, S. (2004, March 15). Blind faith. Nation, 278, 34-37.

Limbaugh, D. (2003, July 9). Mel Gibson’s passion for “The passion”. Townhall.com. Retrieved September 7, 2004 from http://www.townhall.com/columnists/davidlimbaugh/printd/200370shtml.

Mahan, J. H. (2002, February). Celluloid savior: Jesus in the movies. Journal of religion and film, 6. Retrieved September 14, 2004 from http://avalon.unomaha.edu/jrf/celluloid.htm.

Meacham, J. (2004, February 16). Who killed Jesus? Newsweek, 143, 45-53.

Medved, M. (2004, March). The passion and prejudice. Christianity Today, 48, 38-41.

Mel is as he was. (2004, February 27). Commonweal, 131, 5-6.

Miramax Film Corp. (Ed.). (2004). Perspectives on the passion of the Christ. New York: Hyperion.

Mitchell, E. (2004, February 8). Mel Gibson’s longstanding movie martyr complex. New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2004 from http://www.nytimes.com

Nashawaty, C. (2004, March 12). Crossover hit. Entertainment Weekly, 755, 13.

Neff, D. (2004, March). The passion of Mel Gibson. Christianity Today, 48, 30-35.

Nickel, J. (2004, May-June). ‘Visions’ behind The passion. Skeptical Inquirer, 28, 11-13.

Noonan, P. (2004, March). Keeping the faith. Reader’s Digest

Noxon, C. (2003, March 9). Is the Pope Catholic…Enough? New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2004 from http://www.nytimes.com

Parenti, M. (2004, September/October). Jesus, Mel Gibson, & the demon Jew. Humanist, 64, 22-24.

Pelikan, J. (1999). Jesus through the centuries: His place in the history of culture. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Phillips, K.R. (1999). A rhetoric of controversy. Western Journal of Communication, 63 (4), 488-510.

Rich, F. (2004, March 7). Mel Gibson forgives us for our sins. New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2004 from http://www.nytimes.com

Rich, F. (2003, September 21). The greatest story ever sold. New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2004 from http://www.nytimes.com

Rich, F. (2003, August 3). Mel Gibson’s martyrdom complex. New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2004 from http://www.nytimes.com

Rich, F. (2004, January 18). The Pope’s thumbs up for Gibson’s ‘Passion’. New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2004 from http://www.nytimes.com

Riley, R.(2003). Film, faith and cultural conflict: the case of Martin Scorsese’s The last temptation of Christ. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

Safire, W. (2004, March 1). Not peace, but a sword. New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2004 from http://www.nytimes.com

Scham, S. (2004, March/ April). Hollywood holy land. Archaeology, 57, 62.

Scott, A.O. (2004, January 30). Enraged filmgoers: The wages of faith? New York Times. Retrieved March 15, 2004 from http://www.nytimes.com

Scott, A.O. (2004, February 25). Good and evil locked in a violent showdown. New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2004 from http://www.nytimes.com

Scott, A.O. (2004, February 7) The ‘Passion’ of moviegoers. Fort Worth Star-Telegram, pp. 3F, 5F.

Smith, S. (2004, March 22). Put your money where your movie is. Newsweek, 143, 52-53.

Sullivan, A. (2004, June). Jesus Christ, superstar. Washington Monthly, 36, 48-52.

Tatum, W. B. (1997). Jesus at the movies: a guide to the first hundred years. Santa Rosa, CA: Polebridge Press.

Thompson, A. (2004, April 12) Holy week pilgrims flock to ‘Passion’. New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2004 from http://www.nytimes.com

Travers, P. (2004, February 23). The passion of the Christ. Rolling Stone. Retrieved

March 15, 2004 from http://rollingstone.com/reviews

Van Biema, D. (2004, April 12). Why did Jesus die? Time, 163, 54-60.

Waxman, S. (2004, March 15). Hollywood rethinking faith films after ‘Passion’. Retrieved April 19, 2004 from http://www.nytimes.com

Waxman, S. (2004, February 26). New film may harm Gibson’s career. Retrieved April 19, 2004 from http://www.nytimes.com

Widdecombe, A. (2004, April 5). Mel Gibson and the passion: Why the Jews are wrong. New Statesman, 133, 18.

Wilmington, M. (2004, February 24, 2004). Movie review: ‘The passion of the Christ’. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved March 15, 2004 from http://www.metromix.com

Woodward, K.L. (2004, February 25). Do you recognize this Jesus? New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2004 from http://www.nytimes.com

Zaleski, C. (2004, April 20). Scandal. The Christian Century, 121, 35.

Friends We Will Miss: David Bordwell (1947-2024): If one writer can be said to have been the leading voice of academic film studies in America, it was undoubtedly David Bordwell. His seminal work Film Art: An Introduction, first published in 1979 and revised and updated consistently over the ensuing decades, was required reading for most subsequent undergraduate students of cinema, while his other books and countless essays provided the framework for many an upper level film studies course (his 1979 essay "The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice” is a personal favorite of mine). Anyone who ever took a serious academic film course at college beginning in the 1980s and continuing through today knows the name of David Bordwell and his wife and collaborator Kristin Thompson. Like Jonas Mekas, Andrew Sarris and Roger Ebert, Bordwell was among the great tireless evangelists of cinema who saw film viewing as something of a religious act. He was more apologist and explicator than high-brow critic and he represents an ever-vanishing generation of serious and meaningful film writers that is sorely missed today. Thank you Dr. Bordwell, you taught us a great deal. We were blind and you helped us learn to see.