New Sensations, Growing Up in Public, and the Beginning of a Great Adventure

Encounters with the Late Great Lou Reed

On this day a decade ago, we lost Lou Reed. For many of us the world has never been the same knowing he is no longer chronicling its dark, poetic alleyways. The King of New York is dead. Long live The King! The following is an excerpt from a work-in-progress titled From The Heart.

Other than your sprawling passions for all things punk, there were two great singular loves in your final year of high school, post-Kelly. One was exchange student Cecilia Rossel, a passion which lasted until she returned to Sweden that summer, while the other would span a lifetime. Watching MTV one afternoon late in your junior year, you discovered Lou Reed. The song was a rockabilly-style number called “I Love You Suzanne” and the singer was something of an older guy, a tough, muscular New York greaser type in dark sunglasses and a black T-shirt. There was the indefinable taint of punk about him, but also something of classic rock royalty, a sense of dirty boulevard pedigree. Although you weren’t quite familiar with him, his name and persona were instantly recognizable from the Creem magazines of your childhood and you were immediately obsessed, possessed even, upon seeing this admittedly not-so-great music video. You breathlessly set out to the local record store to buy his new album New Sensations, which featured the song, and you played it over and over. Not long after, you found a tape of Reed’s Growing Up In Public in the bargain bin of another shop and snatched it up; it was even greater than the new album and much more strange and avant-garde. The lyrics were the very spirit of pure poetry:

A son who is cursed with a harridan mother

Or a weak simpering father at best

Is raised to play out the timeless classical motives

Of filial love and incest

Who writes like that? Who was this amazing performer and songwriter and how many albums did he have? You asked your heavy metal rock god brother about this Lou Reed and he responded, “Oh, yeah. ‘Walk on the Wild Side.’ Cool song.” Somehow, you had never managed to hear Reed’s only big radio hit (a collaboration with David Bowie no less!) from 1973!

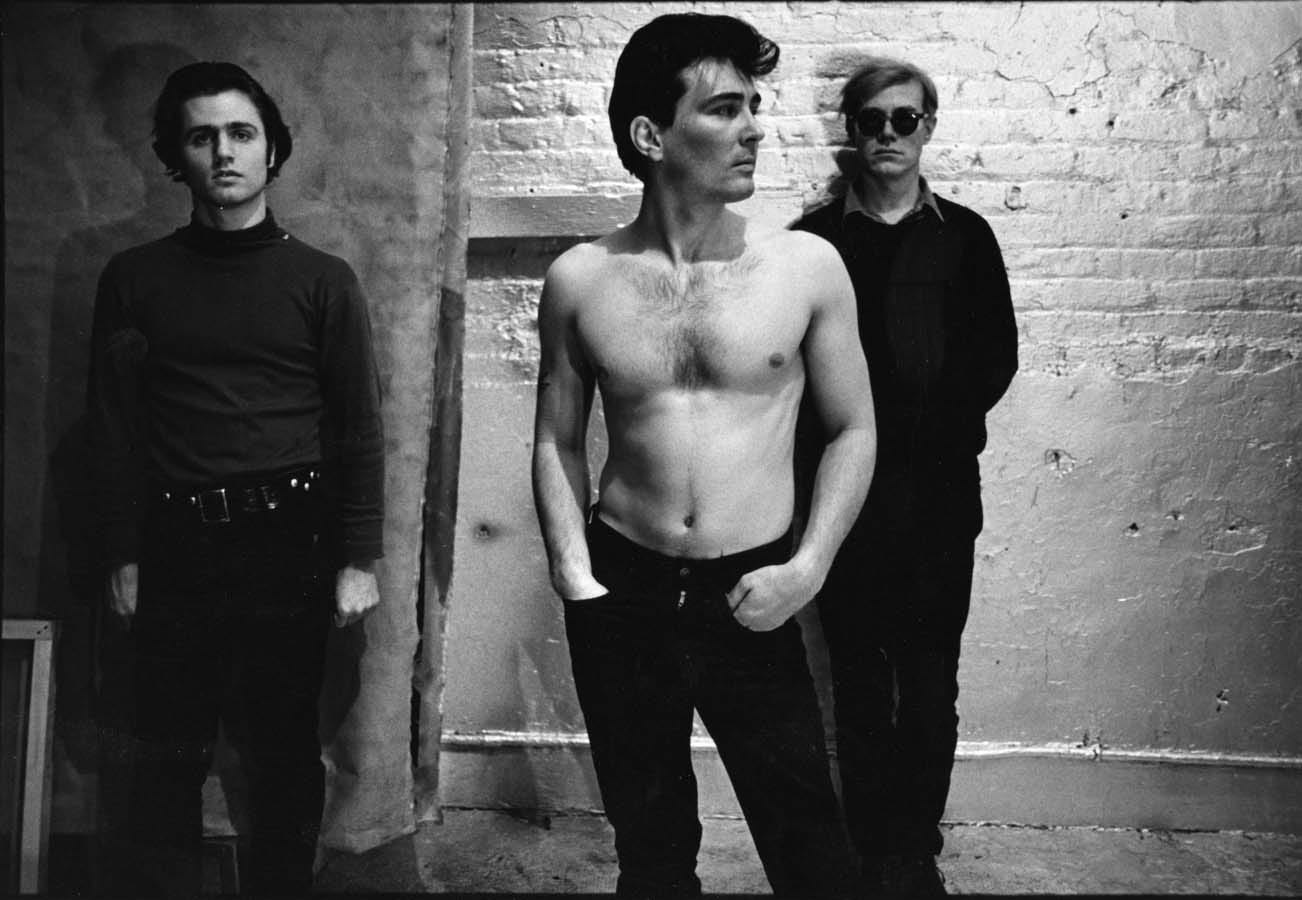

This moment of awakening was accompanied by a reawakening obsession with Andy Warhol that was shared among the members of your “gang”, the New Mutants. You had always felt you were a soulmate to your late uncle and were fascinated by his unknown history with Warhol. A framed photo in your grandmother’s hallway showed your shirtless uncle standing between an icy Warhol and another downtown hipster you would later learn was the poet Gerard Malanga (with whom you would later spend a day in New York following a lengthy correspondence). The three men looked infinitely more like your punk and new wave friends than anything related to 1960s hippies. You would often meditate on this image when you were at your grandparents’ home; it was full of mystery and menace in much the same way punk rock was. Warhol’s 1960s Factory was the first New York punk scene and had laid the template for the weird cutting edge rock demimonde that coalesced at CBGB and Max’s Kansas City in the middle 1970s with acts like Talking Heads, Richard Hell, Television, New York Dolls and Patti Smith. As your new friends shared and encouraged this obsession with Warhol and your uncle, your family also supported it. For your 17th Christmas, your Nana gave you the book Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up by Bob Colacello while your parents ordered you a year’s subscription to Interview, Warhol’s oversized garish and arty monthly celebrity and culture rag.

You videotaped anything related to Warhol that aired on MTV and Night Flight. Amy Williams also had some unremembered family connection to Warhol and one wall of her parents’ living room was completely taken up by a massive framed piece of the artist’s “Cow Wallpaper.” It was probably Amy who got everyone reading Edie: An American Biography, which chronicled the troubled life and death of Warhol’s doomed superstar but also provided an oral history of the whole spectrum of Factory denizens along with a section of stunning photographs of the same. And there among many other fabulous creatures was a young Lou Reed! The Velvet Underground, so you read, was Lou’s band from the 1960s and was also the house band of Warhol’s Factory. Warhol had even produced some of the group’s music. As you interrogated your friends about all this, the amazing Jonathan Brown casually mentioned he had the Velvet Underground’s first album, “You know, the Warhol one. The Banana album.” You insisted that you accompany him to his house immediately after school to listen to it. The Velvet Underground and Nico was mind-blowing and some of it was the most aggressive, experimental punky noise you had ever heard. Jonathan seemed to think the record’s out and out cranky strangeness was something of a humorous novelty, and as “Heroin” reached its shuddering insane crescendo, he mimicked shooting up dope and pushing down the imaginary plunger in a frantic repeated rhythm, as though it was the faulty plunger of a rusty syringe rather than the band making the infernal racket bursting from his not inconsiderable hi-fi system. But this was no laughing matter, this was simply astonishing! You demanded he make you a cassette of the record, which he handed you at school the next day. Side B of the tape contained White Light White Heat, the band’s second album. This stuff put the Lou Reed legend in proper perspective. Although you never could find any of the original Velvet Underground albums during that period, you bought up their two live albums which were easier to find along with every Lou Reed solo album you could get your hands on. You were hooked on a hard drug known on the streets as Lou Reed.

You repeatedly rented the VHS of A Night with Lou Reed at the local video store, which captured a stunning 1983 performance at the Bottom Line in Greenwich Village with blistering guitar attacks by Robert Quine and Warhol snapping photos in the audience. One weekend, Night Flight aired a quirky rock & roll comedy called Get Crazy, which featured Reed playing a version of his own mythology as a mysterious and reclusive underground folksinger alongside Malcolm McDowell, Clint Howard, Dick Miller, Paul Bartel, Warhol siren Mary Woronov, Daniel Stern from Diner, and Lee Ving, frontman of LA punk band Fear. Reed and Fear also featured on the soundtrack, as did Sparks and The Ramones. Directed by Alan Arkush, Get Crazy was every bit as funny and cool as his previous film, the Ramones-driven Rock ‘n’ Roll High School.

When Leslie Lee lent you her Violent Femmes tape around that time, you were pleased by that band’s obvious similarity to Lou and the Velvets. Reading books like Lou Reed and The Velvet Underground by Diana Clapton (your 18th birthday present from Cissi, Amy and Julie) led you into a secret history of rock and roll with firm connections to punk. The Velvets had practically invented the genre, but there were a number of trashily glammed-up protopunk bands who had similarly paved the way forward in the late 60s and early 70s: The Stooges, MC5, Bowie, T. Rex, New York Dolls, even the Rolling Stones and The Who. But Reed and the Velvets in particular seemed to have inspired virtually every New York and British punk act that had come after them. Like Bowie, who shepherded Lou to his only big radio hit, Reed was an androgynous shape-shifter, moving through various guises and visages through the years. But unlike Bowie’s constant reinventions, Lou Reed’s essential persona seemed somewhat consistent; the hardboiled poet of the nocturnal New York streets. Bowie was from the stars, Lou was from the gutter. Bowie was cold and alien, apocalyptic and otherworldly, Reed was cool, confident, cynical, and ready for street action. He was your hero. Much like Mickey Rourke, Reed was everything you wanted to be at 17. Your fandom was so legendary that all these years later, friends and family members continue to associate you with Reed (and Bowie as well, but everyone owns Bowie these days). You never could have imagined that not only would you eventually get to see Lou Reed perform live three times but would also have pleasant and meaningful exchanges with the notoriously cantankerous avant-rocker on all three occasions.

When your mother asked you what you wanted for your 18th Christmas, you made out a list of records that included “anything by the Velvet Underground!!!” Nana and Mom actually drove all the way to your favorite used record store in Irving and found several incredible slabs of vinyl. Among these was a rare promotional record featuring an overview of the band’s catalogue; the other was a coveted promotional copy of Loaded, the Velvets’ fourth and final studio album. Meanwhile Jeff Christian gave you a rerelease copy of Reed’s The Blue Mask and Jonathan found you an original copy of Berlin, which included a beautiful booklet of lyrics and images. These were epic and unsettling records, raw beauty that was immediately burnt into your mind and soul. It was a very good Christmas. A mere couple of months later, the Velvets finally emerged into the Overground. You and Steve Zimmerman were working at Camelot Music when Verve unleashed the first of two volumes of previously unreleased material by the 1960s noise pioneers, along with rereleases of the band’s first three records. It was an exciting time filled with some absolutely incredible music. Punk Godfather Lou Reed’s edgiest era was now the stuff of popular culture.

Each Reed record you discovered was a revelation and an instant favorite: Transformer, Sally Can’t Dance, Coney Island Baby, Rock and Roll Animal, Street Hassle, Take No Prisoners, Live in Italy, Legendary Hearts, eventually New York and Songs for Drella… There seemed to be no end to the gritty aural ecstasy of these hardboiled audio movies. Friendships were often forged and maintained based on a mutual addiction to all things Reed. You had known Matt Garrett since junior high school before reconnecting with him through a shared passion for David Bowie your sophomore year and by the 12th grade you were inseparable once again, brought together by Reed and blazing together through the suburbs in one jalopy or another blasting out Reed’s incendiary live Lenny Bruce routine for all to hear, trying to gather more converts. Your friends as always ensured that you continued to feed your desperate Reed habit as you entered days of college then skid row: Chad Clemons gave you a VHS copy of the Songs for Drella concert one year for your birthday and Joe Patterson presented you with a framed vintage poster from Lou’s Street Hassle tour stop in Austin. Joe was your roommate and close companion and confidant on two occasions; first in Denton where you briefly attended university in the late 1980s then in Austin in the middle 90s. Joe was likewise a big admirer of Reed and was also prone to hilarious impressions of Lou and liked to take the piss out of him. He would look at a photo or album cover featuring the phantom gutter rocker and then tell you what Reed was thinking or saying with a pitch perfect deadpan Lou gaze and emotionless New York intonation: “I’m just going to hold the sword like this.” You had to be there but it was pretty hilarious. Joe also coined the phrase “The Lou Freakout” to identify a phenomenon that occurred in a lot of Reed’s live performances when the singer seemed to forget the lyrics to his songs and would fill in the gap with a lot of “Oh, baby. oh, baby” and “Ah, ha, ha, ha, ha” and the like. When you lived together in Austin, you and Joe attended a South by Southwest screening of the then-new documentary Lou Reed: Rock & Roll Heart, which blew you both away. Afterwards, Joe remarked in typical Joe fashion that it was difficult to tell Lou Reed and Joe Piscopo apart during a certain period in the 1980s. It was a sheer joy to listen to and talk about Reed with guys like Matt, Chad, and Joe.

Driving to dirty old Dallas just to go to record stores and look for rare and precious punk and Lou Reed records was always a big event in your young lives and was a perfect outing for friends. There was VVV, Record Gallery, Metamorphosis, Assassins, RPM and Direct Hit. And then there was Bill’s Records.

“Head for Bill’s!” was the shop’s motto and it was ubiquitous in the middle-eighties, plastered on bumper stickers and shouting out from print advertisements. Those in the know understood the message clearly: If you were reasonably-good-looking- and so very few young boys are really ugly, let’s face it- and you provided Bill with oral gratification, he would give you an incredible discount on the records you bought. As Bill was a middle-aged gay man, this special offer only applied to good-looking boys. While you never knew of anyone taking Bill up on this sort of transaction everyone was well aware of the option and plenty of guys were suspects. Bill’s shop was considered the best in Dallas; it was a sprawling warehouse-like space, dark and cavernous, filled with rack after rack of rare used records, all lovingly organized. The shelves and walls were festooned with posters, flyers and autographed memorabilia. You could spend the better part of an afternoon in there and still not go through it all, and you always ran into kids you knew and met new friends there. Presumably due to the standing blow job discount offer, nothing in the store was priced, you had to take any record you were interested in to Bill and he would arbitrarily tell you what he deemed it to be worth. Bill himself was a charming guy, if a lecherous old flirt. He made no effort to downplay the fact that he was always on the prowl for gay sex; the moment he saw a cute young dude walk in the store, he would approach him immediately and try to close the deal without actually outright saying what he wanted. He would look the boy deeply in the eyes and smile around the Turkish cigarette perpetually in his lips and sweetly whisper-talk his knowledgeable responses to queries about this or that album. Even though his shop’s clientele primarily consisted of heterosexual punk kids, he seemed to see his business first and foremost as his personal cruising arena and pickup joint. It was quite hilarious and all the young punks loved Bill and the record store; it was as much a hangout as a shopping destination. On one trip to Bill’s, you had gotten very high with Spaz and Jean on the ride there and found yourself feeling a little confused, foggy, incommunicative and paranoid. You had brought in some of your own rare records to trade in or barter with. You left the stack of vinyl with Bill to look through and make a credit offer, then proceeded immediately to the Lou Reed section. As was your way. There you discovered an original pressing of Street Hassle, which was not only quite rare and difficult to find but also one of Reed’s very best albums. Furthermore, Bill’s copy was actually signed by Lou! You felt faint and very stoned as you walked back to the counter to get a price from Bill. As you stammered and tried to avoid Bill’s horny piercing gaze, he told you $30 for the signed Reed LP, this was a fortune back then. As you tried to collect your senses, you continued to try and work through the weird pot haze in your brain and referred Bill to the albums you had brought in to potentially trade. “What about…,” you stuttered. Bill looked very hopeful. “What if I gave you…” Bill was positively beaming as you struggled to express yourself coherently. “Would you let me…” He was now quivering with anticipation as the barter seemed to be steadily moving in the right direction for him. “What if I gave you both the Dead Kennedys albums? How much would you knock off the price of the signed Lou Reed record?” Bill appeared deflated and defeated as he agreed to knock $10 off the purchase with the trade in you suggested. You had scored a pretty good discount but it had not gone the way poor Bill had hoped.

A decade after discovering Lou Reed, you were a sailor in New York City during Fleet Week and you went to a spoken word show you had read about in the Voice at the fabled Bottom Line featuring Jim Carroll, Hubert Selby Jr., and Maggie Estepp, poets and performers all sharing much in common with Lou Reed. These were his people, his friends. You met Selby that night after the show, and throughout the night you were seated at a table with a New York guy who thought it was crazy cool that you were spending your liberty evening at a punky literary event in the Village. He also told you that he was there to meet with Selby, as he was currently adapting one of his novels to film. That guy was Darren Aronofsky, director of Requiem for a Dream and later, Mickey Rourke’s comeback film The Wrestler.

In 1996, your parents sent you a care package while you were at sea with the Navy, which included a review of Lou Reed’s recent concert in Dallas. You were almost physically ill when you discovered that after all these years, he had finally rolled through town when you were sitting off the coast of Israel. You were also disgusted to learn that he had played to only a half-full Bronco Bowl and you cursed the philistines of the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex. It seemed you were destined to never see your hero perform. Your dad also sent you Lou’s current CD Set the Twilight Reeling around the same time. Like Dad, Reed just seemed to get better and better with age.

Three years later, you were recently married and back in Fort Worth when you read that Lou Reed would be performing at the Knitting Factory in New York City. Your lovely bride’s favorite artist was Laurie Anderson and, bizarrely enough, Laurie was now betrothed to none other than Lou Reed. This seemed to bode well for your new marriage and apparently has done. You immediately booked flights and concert tickets, even buying tickets for two of your friends who lived in Manhattan. You were also shooting some scenes for your first feature film guerilla-style while you were there and ended up giving Reed a thank you credit in it. The show was absolutely incredible and Lou with his usual crew performed nearly every song off his soon-to-be-released album Ecstasy, which would prove to be a career highlight. After the show, your friends took off but you and Sherry stuck around by the exit with a crowd of other fans as you clutched your copy of Reed’s collected lyrics. Suddenly, Lou and Laurie Anderson emerged from the venue, led by a team of burly biker bodyguards. Reed made eye contact with you and gave you a kind of smile and you shouted, “Hey Lou!” The crowd behind you went a bit wild and a young fan beside you, a rather ridiculous looking kid in top hat and full glam rock regalia, pushed in front of you with a stack of albums for Lou to sign; this caused you to bump rudely into Laurie Anderson. “Sorry Laurie,” you said and she gave you and the glittery overzealous kid an irritated look with the faintest trace of a smile. Then Lou totally ignored the kid pushing his albums in his face, instead he looked over at you, kind of sized you up for a moment, and said, “What were you trying to tell me?” You were face to face with Lou Reed. You breathlessly told him how you had been hoping to see him since you were 16 years old and how much his music had meant to you through the years. He actually seemed very touched by what you said, he had the sweetest, slightly embarrassed expression as he signed his book for you and thanked you in a soft whisper. It was an incredible end to perhaps the best night of music you had ever experienced. The next day when you told your friend Dustin about the encounter and how Lou had purposefully blown off the younger fan to have a word with you, Dustin said he wasn’t surprised at all, as you and Reed were “cut from the same cloth.” It was the ultimate compliment. Oddly enough, when you visited NYC the next year, you found yourself hanging out with Abel Ferarra, a filmmaker you worshipped much like Lou and who was also cut from the same cloth, another “King of New York” and chronicler of the city’s dirty boulevards who mixed high art and exploitation sleaze to create a seedy street poetry remarkably similar to Reed’s, a kind of cinematic counterpart.

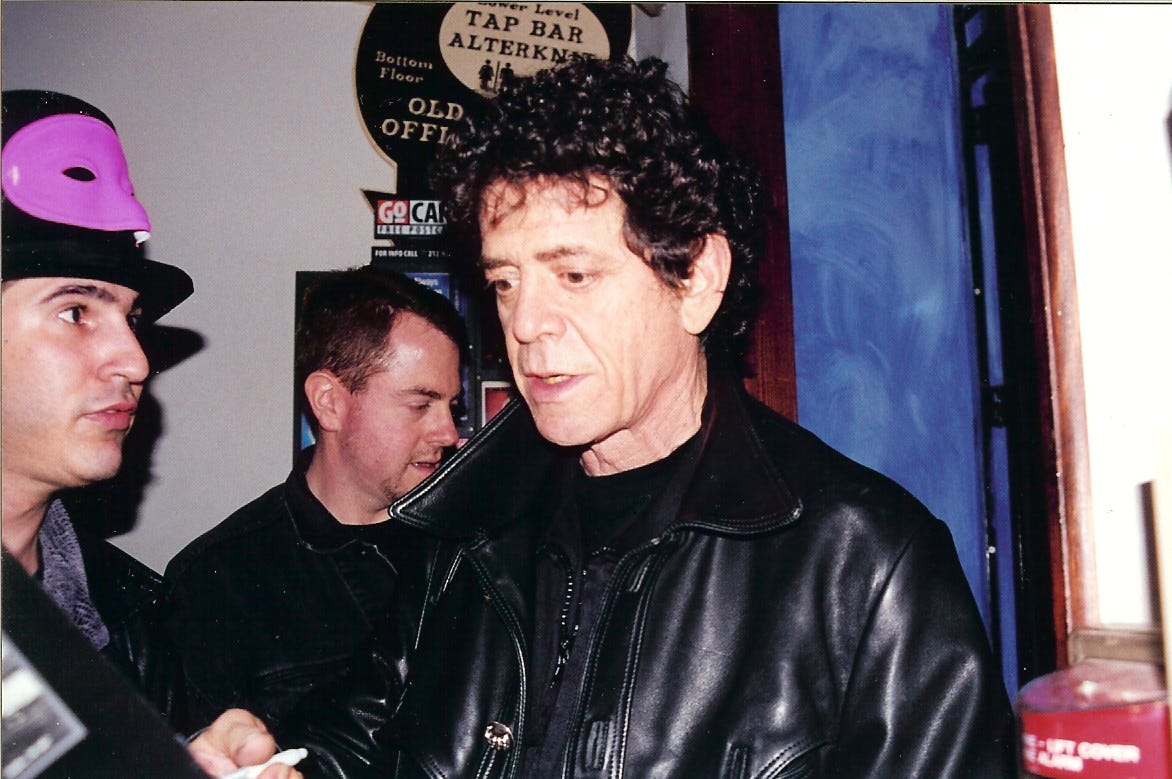

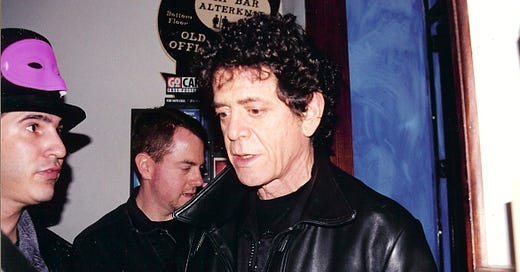

Lou at the Knitting Factory, 1999. Photos by Sherry D. Montage by the author. Music by Lou Reed and Ornette Coleman.

You returned to New York to see Reed again in 2003. Not only was he playing a gig at Town Hall but he was doing a signing at Tower Records the day before. After ordering concert and plane tickets, you called Tower long distance and explained that you were coming in from Texas and wanted to purchase a copy of Lou’s upcoming NYC Man compilation over the phone with your credit card; you had to buy the 2 CD set from Tower in order to attend the signing. The Tower guy didn’t know what to make of your request and seemed annoyed; telling you “This is highly unorthodox!” Eventually the sale went through and when you arrived at the store and asked for the clerk who had sold you the CD so that you could get a badge for the signing, the guy turned out to be really nice and thought it was very cool that you had come all the way to New York to see Reed. You filmed Reed once you got close enough in line to see him, then passed the camera to Sherry to film your encounter with him. Despite his image as the rudest rock star on the planet, Reed was once again extremely kind to you; he even seemed to remember you from 2000. You had him sign the three items you were allowed and gave him a copy of your collected short films on DVD. He seemed to think this was rather novel; he likely received music CDs from fans all the time and the films seemed to strike him as a legitimate gift rather than someone trying to get a foot in the music biz door. “Thank you. Thank you,” he said softly and if it was the least bit insincere, there was no evidence of it. You told him that he was a key inspiration on your filmmaking and he gave you the same sheepish smile as before. He thanked you once again, shook your hand, and you reluctantly ceded your lofty position to the next in line. Sherry was a few people back in line so that she could get more stuff signed and film you and Lou together. When she asked to have a CD signed to Phil and Sherry, Reed cheerily said, “Oh, yeah. I know Phil. Where’s Phil?” By then you had moved up near the table again to film them and you blurted out, “Here I am, Lou!” Lou gave you a big grin and said, “There you go!” The next night was the concert, which was another incredible performance and you were able to film some of it before an usher found you out. Reed was performing in support of both his NYC Man greatest hits collection and his new star-studded double CD spoken word Edgar Alan Poe concept album, The Raven and he rocked the house with a number of special guests joining him on stage. This was quite an eventful escape to New York; that same trip you met and hung out with Larry Fessenden, one of your very favorite filmmakers, at his editing studio on the Lower East Side, and you also saw Matthew Barney’s astonishing Cremaster installation at the Guggenheim, along with two of the Cremaster films.

Your final encounters with Lou Reed took place in Austin, Texas in 2008 a few months after moving to the city for the second time after three years in Chicago. It was announced that the keynote speaker for that year’s South by Southwest Music and Film Festival would be none other than Mr. Reed and that he would also be presenting his new Berlin concert film, although he wouldn’t be playing a concert (although he did surprise a packed house during the fest by sitting in with Moby). You were quite poor and could not afford the pricey festival pass, so you volunteered as a doorman for the music fest, which would at least allow you access to the daytime screening; however the keynote address was strictly for badgeholders. You were determined to figure out how to get into that as well. During volunteer orientation, Louis Black, founder of the Austin Chronicle, the Austin Film Society and SXSW, announced that there were a lot of fake entry wristbands about and that people were sharing them as well. Louis encouraged us to be vigilant, to look for wristbands that did not look right and were not tightly bound to the wrist or were stapled, etc. He said that we were to confiscate such wristbands as we spotted them and that there would be a daily reward for the volunteer that collected the most. Bingo. Your first night working, you were militant, snatching wristbands and ejecting festivalgoers right and left and amassing a huge bundle of errant credentials. At 4 in the morning, you returned to the festival headquarters to be paid and processed for the night. You told a supervisor that you felt you had without doubt confiscated more bogus wristbands than anyone else. After the tallies were in, this was indeed confirmed. The supervisor dumped a bag of cheap SXSW swag on the table, t-shirts, sunglasses, etc. and told you to take what you wanted. No, no, no, you protested. “Tell Louis Black I want to go to the Lou Reed talk.” He looked a bit puzzled. Suddenly, a distinctive raspy voice called out from across the room. “Hey! C’mere!” You walked over and were face to face with the somewhat intimidating Louis Black. He wrote you out a handwritten note on a piece of paper which stated you were to be given an all-access press pass for the following day and signed it. Early the next morning, after about an hour’s sleep, you arrived at the Austin Convention Center with your video camera and were ushered through to the keynote address. After Black introduced him, Lou admonished him for failing to also introduce his interlocutor, the visionary record producer Hal Willner who had a long history and friendship with the cranky singer-songwriter, then Lou and Hal settled in for a wonderful hour-long conversation on a wide variety of topics. As a “member of the press,” you were allowed to move up front to film the first 10 minutes of the talk alongside an army of clicking-away photographers. When this was period was over and you were asked to move away from the stage, you rather too loudly uttered “Fuck!” and Lou looked over at you as you moved away, still filming him. After the talk, you were in a dream world as you also attended and filmed uncrowded press-only performances by Billy Bragg and Martha Wainwright.

The next day, after another very late work night at the clubs, you attended the screening of Reed’s mind-blowing concert film Berlin, followed by another long chat by Lou and Willner. During the Q & A session, you got called on by Reed and asked him if the soundtrack for Time Rocker, the avant-garde theatrical production he had created with Robert Wilson, would ever be released. Lou responded, “Well, you’re probably the only person in this audience who even knows what the hell you’re talking about. Let me explain a little,” before proceeding to do so. It was quite thrilling to be acknowledged as a Lou Reed expert by the man himself. After the talk, Reed and Willner moved to the side of the stage and were just hanging out. You cautiously approached them and said hello, shook hands, expressed your admiration for them both. You asked Reed if you might take a photo with him on your phone. “Okay,” he said laconically, throwing an arm around your shoulder and freezing up in his normal unsmiling deadpan expression. You snapped the picture, thanked him and then moved quickly away so as not to annoy him further. In your haste, you did not choose the “save picture” option and immediately erased the image from your phone like an idiot.

Five years later, as the fates would have it, you were attending an Austin Film Festival event on Texas punk cinema hosted by none other than Louis Black and filmmaker Jonathan Demme when you received the news of Reed’s death. Sherry met you at the venue and told you the sad news. You were even wearing the t-shirt you got at the NYC Man/ Raven show in NYC that day. You knew Lou had recently received a liver transplant, but he was reported to be doing well, even by his wife Laurie Anderson, whom you had recently seen at UT being interviewed by Evan Smith for a television broadcast. You remembered how even back in 2008, Reed had seemed suddenly frail and a bit shaky and you had wondered about his health. Now he was gone. The tributes rolled out around the world and here in Austin, including your own at the Austin Film Society and two musical extravaganza memorials hosted by Reed-influenced local punk luminaries Alejandro Escovedo and Jesse Sublett. After the Pandemic, you were fortunate to be able to travel once more to NYC and attend the incredible “Lou Reed: Caught Between the Twisted Stars” exhibit at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.” Rarely a week goes by that you don’t listen to Lou Reed. It still feels like a light has been permanently switched off in the world. Three years later, David Bowie and Leonard Cohen were also gone, followed by Prince the same year and Mark E. Smith of The Fall in 2018. The second decade of the 21st Century was dark and grim indeed. You wondered what calamities the third decade might hold. As Lou Reed might say, Now you know.

I hope it's true what my wife said to me

She says, "Lou, it's the beginning of a great adventure."

Oh,the times we’ve had. That’s one of the best memories, Phil and the excitement of that first Lou Reed concert. He still lights up when he talks about it.