Going Rogue with Werner Herzog

Ecstatic Truths revealed at the Radical German Auteur's Film School, 2010. Part One of Two.

“Phillip wrote words in the sand in front of me: Ocean, Clouds, Sun, then a word he invented. Never did he speak a single word to anyone.” ~ Werner Herzog

Can it really be 14 years ago almost to the day that I set sail with Werner Herzog on the dangerous three-day expedition our fearless captain called the Rogue Film School, all the way back in June of 2010? Our world was a much different planet then. When I arrived back in Austin that summer, I intended to try and publish my notes about this incredible experience but life got in the way, as it will. I did write a rather scatterbrained and overblown introduction to an essay at that time but got no further. Witness:

Rogue Report:

There is a conversation that, among many others, I seem predestined to have again and again. In discussing the virtues- or lack thereof- of DVD commentaries, I often hear from my fellow conversants that they can rarely sit through them. I am forever directing (?) acquaintances of this opinion to the commentaries of a few of my favorite filmmakers who are, insofar as I can judge, peerless in the field of DVD commentary. The very short list includes New York scuzmaster Abel Ferrara and New German Cinema alumnus Werner Herzog. I will return to Ferrara later, but I should state at this point that while Ferrara’s commentaries are laugh-out-loud hilarious in the manner of watching bad porn with a verbose alcoholic uncle, Herzog’s are, to me, more like hushed religious liturgies enacted by a master of mysticism and sublime poetry.

Every bit as fascinating and thought-provoking as the films he urges to life (often at great physical peril and mental risk), Herzog is increasingly known to younger generations for being a captivating and charismatic media personality rather than for the cinematic masterpieces he continues to produce outside of any studio system to speak of. While it may seem odd that one of the world’s greatest living art film directors is too widely known for his contributions to popular cartoon culture- appearances on The Simpsons and The Boondocks for example- it is his eloquent, poetic, and highly intelligent rhetoric coupled with a primal Bavarian Brogue that make both his pop culture forays and his DVD commentaries so incredibly entertaining, thought-provoking, and even trance-inducing. Select the commentary track on one of his DVDs and tell me you are not soon in an hypnotic state. He is quite simply a snake-charmer, a mesmerist.

Such is my fascination with and impression of this director. I should state up front that the Werner Herzog Rogue Film School in New Jersey was a mind-melting three-day trip down Aguirre’s Amazon, into a stream-of-consciousness Dante’s Inferno and back again, all under the shamanistic (a term Herzog derides at every opportunity) mind control of a master poet of the metaphysical and sublime…

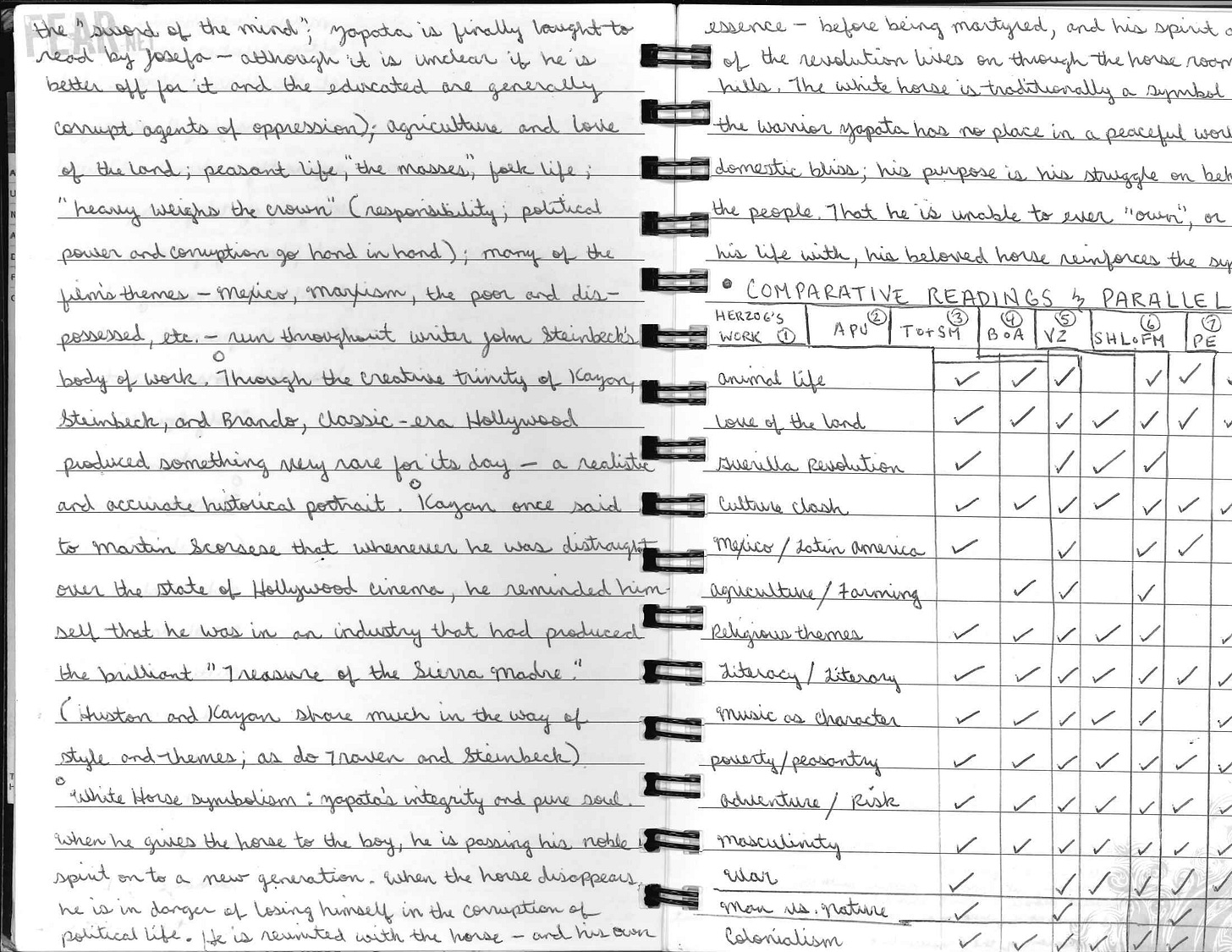

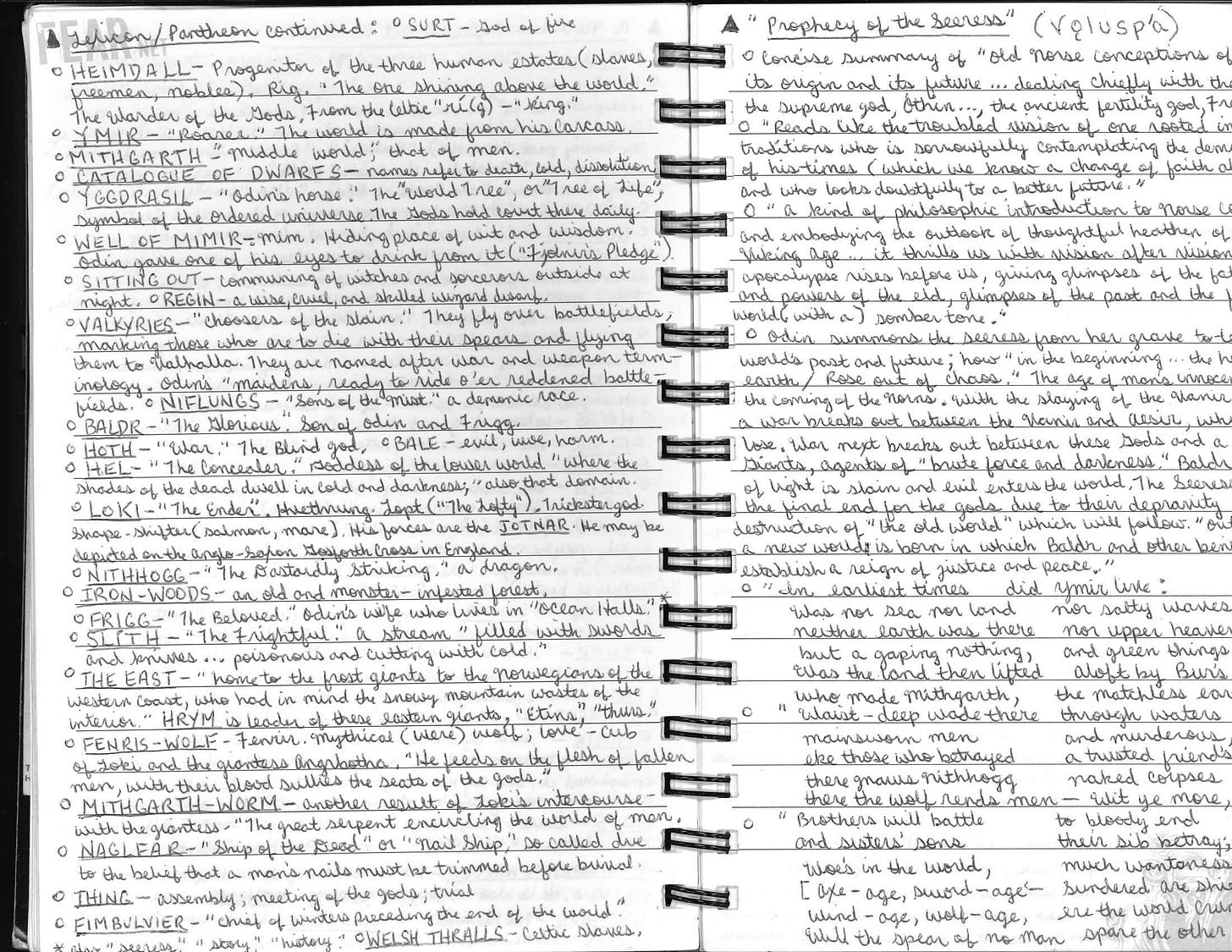

What follows here is an edited transcription of excerpts, a distillation if you will, of the journal I kept throughout my perilous classroom adventure with Herr Herzog. What is not included here are the voluminous pages of preliminary notes I wrote in the same notebook during the weeks before and after attending the class, ranging from Herzog and his cinema to the work of his New German Cinema cohorts (Wenders, Fassbinder, Lommel, Schlöndorff, etc.) to the books and films on the course’s reading and viewing lists, to related books of Norse and Roman mythology, German history and mysticism, the Kennedy assassinations, Goethe, Holderlin, Nietzsche, Rilke, Medieval French literature, Catholic Theology, Scandinavian Black Metal, etc., etc. My solitary monk-like studies were accompanied by a steady soundtrack of Wagner, Gesualdo, Popol Vuh, Faust, Darkthrone, and the like. My lengthy journal entries were often accompanied by intricate charts detailing interrelated themes, comparative literature, and indices of ideas and interpretations. I was apparently quite the scholar back then it would seem. For what purpose I now know not.

During my final exchange with Herr Herzog, which is not included in this installment, Werner urged me to have children in order to keep the spark of creativity alive. I have yet to get around to that for better or for worse. But on that note, I would like to wish my beloved Dad the happiest of Father’s Days here and the same to you if it applies. Thanks as always for reading.

Required Viewing:

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (John Huston, 1948)

Viva Zapata (Elia Kazan, 1952)

Where is My Friend’s House (Abbas Kiarostami, 1987)

The Battle of Algiers (Gillo Pontecorvo, 1966)

The Apu Trilogy (Pather Panchali, 1955-1959)

Required Reading:

Virgil’s Georgics

“The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” by Ernest Hemingway

Suggested Reading:

The Warren Commission Report

Gargantua and Pantagruel by Rabelais

The Poetic Edda translated by Lee M. Hollander

The True History of the Conquest of New Spain by Bernal Diaz del Castillo

Thee Eve, June 11: Preparations for the Expedition.

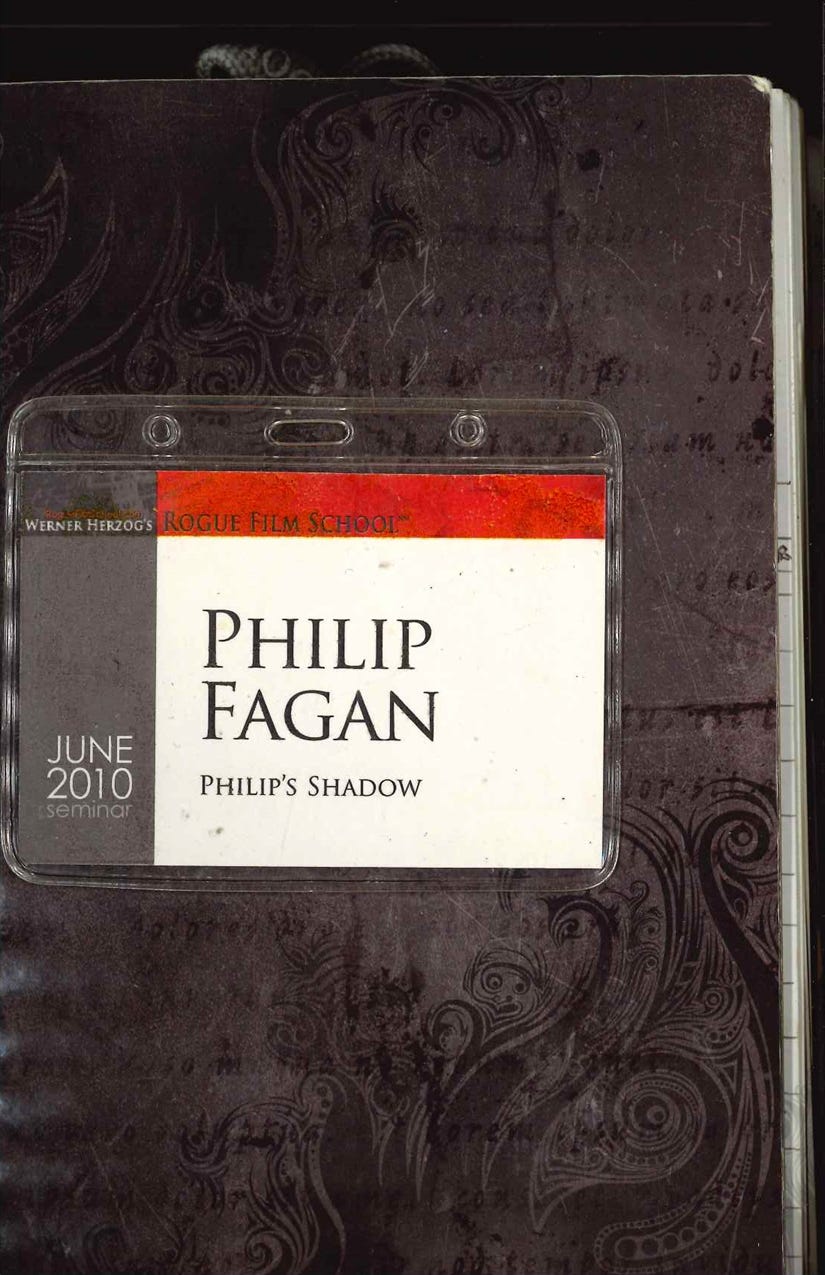

Arrived by taxi at 5:30 PM after various confusions regarding a shared shuttle to the hotel. Checked into my room, then downstairs for the meet and greet. Herzog’s assistant Bernie ushers the gathering throng from the buffet table into the lobby to pick up our credentials. I am third in line at the table when Werner Herzog himself strolls up with a huge grin, jaunty of pace, tall and svelte, his appearance remarkable in a well-worn suit. He stops at the first Rogue he sees by the check-in table and shakes hands, looking at the star-struck student’s credentials: a card on a lanyard with the budding Rogue filmmaker's name and the title of the work submitted for acceptance into the course. Then Herzog has a brief exchange about the student’s work, telling him what he liked about it. He greets each of the Rogues in the same manner, immediately knowing our work after seeing our names and project titles on our credentials and welcoming each of us cordially, very open and intimate eye-to-eye facetime from the get-go. In his hand he has a list of his pupils and places a check mark next to their names as he interacts with them. It was quite incredible that he had screened everyone's films, was familiar with each one, and had something meaningful and positive to say about the submitted work of each student he greeted. As for the assembled gallery of Rogues, we stole furtive glances at each other, all conveying the same astonished expression of, “Sweet Jesus, we are here talking to Werner Herzog!”

As I shake his hand when it is my turn, I notice Werner is sporting a fresh battle scar of black and and blue fingernails. “Werner, what’s the story with your war wounds there?” I had hoped it was the result of dragging his nails down the side of a cliff as he faced imminent death while mountaineering, or perhaps the marks of a pygmy’s bite on the hand, a sign of greeting in some quarters I am told. He looks at his fingers and chuckles. “It’s not very exciting actually. I shut them in a car door.”

So many interesting far-flung adventurers here- Rogues from the US, Mexico, Norway, France, Ireland, Africa, Canada, and parts unknown. Werner soon called the excited revelers at the buffet table and cash bar to attention and we gathered around him. He thanked us all before stressing the importance of reading and film viewing and asking for a show of hands from those who had screened certain films and read particular books on the list. He praised the opening sequence of Viva Zapata!, the entirety of The Battle of Algiers, the magical poetry of Virgil’s Georgics, and “the sheer obscene Joy” of Rabelais' storytelling in Gargantua and Pantagruel. After a few more remarks, he introduced his small staff which to my delight included Paul Cronin, the accomplished documentarian and co-author of Herzog on Herzog, a favorite film book of mine. I had actually considered bringing my copy of it on the trip but had decided against it since I was still finishing up both the Rabelais book and The Conquest of New Spain by Diaz. I spoke at length with Paul and we seemed to hit it off- we were both avid historians of the 1960s underground- then we walked over to where Werner was conversing with two cool cat Mexican Rogues, one of which was Ernesto Anaya Adalio with whom I would spend a lot of the evening discussing his film about an old theater in Mexico City. I soon discovered that Ernesto had also worked on Mel Gibson’s Herzogian epic Apocalypto in Mexico and he said that Mad Mel was a horribly unpleasant man whose temperament was made even worse by the pending divorce suit brought against him by his new young Russian (not for long) wife. “That’s great, huh?” Ernesto continued. “She have his baby, marry him, then divorce like that. Get lots of money for just a little time with him.” I asked Ernesto what his job on Gibson’s film was. “Cucarus,” he replied. I assumed he had misunderstood the question and that Cucarus was perhaps a rural province of Mexico City where the film was shot. So I asked again what his crew position had been. “Cucarus,” he said again. We all stared at him blankly. “Cucarus. Cockroach!” We all laughed and I asked him, “So you just got coffeee, ran errands, stuff like that? A PA basically?” “No, no,” he explained. “Cucarus. The cockroaches. I raise them for movies.” Soon Werner called it a night and withdrew, leaving the Rogues along with Paul Cronin to talk wildly and drink in the hotel bar into the wee hours. Like ecstatic children, we were all excited about the first day of school.

A Much Abbreviated Roster of Rogues:

Jeremy Belin: A young, whip-smart Australian who is a walking encyclopedia of film and popular culture, he is immediately holding court surrounded by his classmates. Jeremy used to write dialogue for professional wrestling. Even Werner is absolutely fascinated by him. Upon discovering our bizarre mutual love for both the films of John Cassavetes and professional wrestling, Jeremy suggests we collaborate on a screenplay about the heels and faces of the blood sport with an improvisatory avant-garde sensibility .

Pete Tideman organizes music festivals in remote East Africa. He shares a number of mystical adventure stories that are both eloquent and credible, with mysterious creatures like The Boatman and ghostly Oriental-Muslim bands playing at sunset by the sea. He bears no small resemblance to Bruce Willis, whom he is routinely mistaken for, particularly abroad.

Bob Baldori: A cool cat world-class boogie-woogie piano player (and also lawyer) who is making a documentary on his band’s exploits and unlikely fame in Russia. He had friended me through the Rogue Film School Facebook group because my Little Moses avatar stated that I was born in 1943, so he thought I was the only guy his age in the group. He was a little surprised to find me nearly half his age. It was Bob who revealed to me that Werner’s assistant Bernie had told him that over 800 applicants had been considered for the current Rogue Film School seminar. We were among the 60 people selected. Rarified air.

Bryan Lyttle is fighting the post-Apartheid power and recently finished his documentary on the subversive South African punk band Fokofpolisiekar (Fuckoff police car). He also produces commercials for the Discovery Channel.

Anna Blom, a Scandinavian beauty making an intriguing documentary about a Finnish family attempting to live in the manner of ancient Native Americans.

John “JR” Rekdahl: A wildly insane Swedish free-jazz musician and filmmaker whose handmade experimental works include a remake of Dreyer’s Vampyr, a metaphysical werewolf film in 3D, and a four-hour experimental opus based on just a few lines of obscure Swedish poetry.

Dan McComb from San Francisco; journalist, filmmaker, Silicon Valley tech, and among the original instigators of the Burning Man festival. Dan and I talked at length of the avant-garde music acts from the Bay Area I had worked with and that he was a fan of as well; Mark Growden, Sleepytime Gorilla Museum, Extra Action Marching Band, Faun Fables, etc. We had some really wild, far-ranging conversations.

Day Thee First:

Lock picking, document forging, cave movie/3D, crew solidarity, perseverance, student work, sound, life versus film, painting and landscapes, working with actors, strategies for fulfillment, camera, Joe Bini and editing, structure, narrative, theme.

“Lock picking is a necessary art…”

“As I cannot legally advise you to commit illegal acts, I must be clear that this is in case you ever need to break into your home...”

“Sometimes it is necessary to break into a home. Read The Complete Guide to Lock Picking and practice often, one pick to rotate the cylinder, one to apply pressure to the cylinder. It is very rewarding to open your first safety lock. It doesn't get any better than that!”

“It is very easy to go through barbed wire; it is just meant to scare you away. Lay a plank on it, go under it, cut it. Take matters into your own hands!”

“The world reveals itself to those who travel on foot. People you encounter reveal themselves in a different way. Do not backpack; take only the essentials and be unprotected. Knock on farmers’ doors for lodging; when you've traveled far, there will be no small talk. Break into vacation homes in France - drink wine, finish crossword puzzles, leave a thank-you note, clean up and let them know someone grateful stayed there.”

“This is essential for Rogues: Step beyond what you are supposed to do, be bold and move beyond the structures of law.”

“Forging Documents has been essential to Fitzcarraldo and other films…”

“Be bold to break deadlocks. Be radical and physical. Once I was shot at, I had tested the limitations and so I moved on to the forgery approach, a permit to pull the ship over a mountain ‘signed’ by the president of Peru and cabinet members.”

“Confidence carries the scheme. ‘I've just sent my guy already to the town hall to make it right…’ You can have a fake document in 5 minutes instead of 3 months. Don't lose yourself in Petty bureaucratic details. You should never have a problem with forging documents you need or entering a place you need. Just get on with it. Accept probation for 20 years because you won't do it again in 20 years. Ultimately you may be arrested and thrown in jail for a couple of days. But that is fine. It is no problem."

When Werner’s film reels were confiscated somewhere in remote Africa, Herzog hid the footage and filled the cannisters with sand, saving the negatives from being exposed and ruined by “the stupid, drunken authorities.” He claims that Myanmar, Burma is “the most ruthless police state ever.” He once forged a shooting permit there, but ultimately didn’t have to use it.

“When people notice you filming, lower your camera, nod, and they will usually nod back. That is consent. Be very human and you have few problems.”

“You even have to get releases to show a Picasso painting on a wall. I had to jump through hoops to get Caruso music for Fitzcarraldo. Three different heirs were embroiled in pursuit of legal rights. One was the child of a prostitute Caruso slept with. Enrico Caruso was a pig.”

“The dust cloud of Bureaucracy is as ugly as it is greedy. It wants paper!”

“For Land of Silence and Darkness, the deepest film I've made in my life, I got consent from deaf and blind people through a tactile language of tapping and gesturing.”

“A handshake agreement is better than a huge contract.”

“If you approach a military outpost with a humble attitude you will fail.”

“They would follow me wherever I would take them…”

On The White Diamond, Werner wouldn't allow his cinematographer to go on the prototype airship’s dangerously unpredictable maiden flight; instead he took the camera and went himself. On Rescue Dawn he lost half the amount of weight Christian Bale lost out of solidarity and also convinced Bale to eat real maggots in the film. In La Soufriere, the volcano was about to explode “with the force of many Hiroshima bombs” but Werner went to the island anyway with two cinematographers. “I was sure this man had a different attitude about death,” he said of the old man who refused to leave the town. There were “foreboding signs; fleeing wildlife and snakes drowning…It didn't look good.”

“You as a filmmaker cannot ask your crew to do what you would not do. You have to gather your courage, walk intelligently, and walk first.”

“A very small, dedicated and bold crew is essential. Big crews are clumsy and expensive and everybody gets in the way of shooting, creating problems with permissions to shoot."

The deaf and blind protagonist of Land of Silence and Darkness was raised by nuns in a pious, spartan environment. Herzog thought she should “commit a crime”, so he took her on a motorcycle ride whereupon he shot a pheasant and had her pluck the feathers and cook it. She was “delirious with the thrill of the crime”, poaching. Her attitude toward the film changed in a “mysterious and secretive way” that was inexplicable. He later hired her to babysit his child.

“You have to prepare the soil before you film someone.”

“In the Middle Ages, you could only make religious art. In Soviet times, you could only make Soviet films. Often Genius comes directly out of Strictures. Use limitations and strictures to the film’s advantage.”

In Aguirre, The Wrath of God, Herzog planned a shot of pigs descending a glacier and obtained medication to mellow out the pigs after finding the ideal glacier. Then four out of six crewmembers immediately got altitude sickness. There were no walkie-talkies for communication (he wouldn't demonstrate his infamous whistle because “it is too vicious!” He used it as an action cue to make Klaus Kinski and later Christian Bale run and once used it to stop the beating of a prisoner). Herzog piggybacked one of his ailing team members down the mountain as the afflicted man vomited over his shoulder. Ultimately Werner abandoned the scenario; his instincts told him he would fail. But he immediately came up with an alternative solution, the opening sequence of Aguirre as it now is. There was only one chance to get the lengthy and now legendary shot right. “Switch to Plan B when things would be wonderful but are not doable.” During the Aguirre shoot, he slept in a hut with a hunchbacked dwarf and her nine children and a brood of guinea pigs, which was the family’s food source and which clamored over him all night. When he moved outside to sleep on the rocks instead, he overslept and had to run barefoot over rocks to catch his train to the next location. He would have been stranded there in the jungle for weeks otherwise.

On his upcoming 3D documentary Cave of Forgotten Dreams, the titular cave was sealed off for 20,000 years; “There were bones from Cave Bears and amazing cave paintings.” To convince the French to allow a German to make the film, he pitched it as “a project for the ministry of culture and a director’s fee of one Euro.” To ensure its preservation, the cave was sealed off by a huge vault door, so on shoot days the crew was only allowed in once in the morning and had to stay all day until they were done. They had to configure and reconfigure the complex mirror setup of the 3D camera within the confines of the cave each day. This involved a two-way mirror placed in front of two cameras side by side, “like a police interrogation room.” Herzog was able to manufacture a new camera battery “in 40 minutes” so they could keep filming on one occasion. “You have to be pedantic.”

For Encounters at the End of the World, there was only a two-man crew, a cinematographer plus Herzog himself, who also did sound. “It was more of a spy operation. We had to overcome an Antarctica so remote that even feeding and hydrating one person is expensive. A glass of water cost $15 to process. James Cameron was rejected for his application for a shoot there with a large crew. My proposal was pretty wild and got accepted based on my research of others’ rejections.”

In addition to showing clips from his own work and discussing his own process, Herzog also showed the work of some of his favorite filmmakers- Kazan, Kurosawa, Huston-and screened some of my fellow Rogues’ submitted shorts. Among these was Rafael Bondy’s film on Chernobyl, which Werner praised for its “very fine Rogue attitude.” Of my own submission, Herzog declared it “a brilliant condensation of what is obviously a much longer piece.” Despite all his advice about breaking every rule and restriction, he expressed concern that I had not obtained signed releases from my high-profile interviewees, which struck me as a very unRogue declaration. He suggested I network with entertainment lawyer and fellow Rogue Bob Baldori, who could assist me in clearing rights with the Warhol people. Similarly, Gregg Watt, an accomplished short film director who appears to be an intimate of Werner’s and like Paul Cronin is auditing the class, suggested I look into a New York-based nonprofit coalition of lawyers who might be willing to clear rights with the Warhol people for free.

“The Deafening Silence…”

Herzog also declared that most Rogue submissions paid no attention to sound quality (guilty!), and that three of the four filmmakers that he started out with in Germany in the 1960s never finished a single film because they couldn't master sound. Herzog claimed he takes more care with sound than in setting up shots. “Always record and collect ambiances. Nail blankets to the ceiling if necessary. We all need to be more professional with sound. Never ‘fix it in post,’ especially sound.”

The length of a Herzog long take is often determined by the length of a music track.

The soundscape of Cave of Forgotten Dreams is a montage of drips, heartbeats, and original music to be recorded in Holland next month, “a whole sequence invented around silence.”

“Silence is a powerful element: The complete silence of the cave other than the dripping of stalagmites in Surround Sound (24 hour sound recording). Just listen to a moment, to the silence. Maybe you can even hear the beating of your heart.”

Part of what makes Werner such an amazing and compelling speaker, nay a hypnotist, mesmerist, a snake charmer even, has to do with his speaking in a second language and in his rich Bavarian brogue. While native English speakers tend to get excessively lazy with the language, Werner seems to study dictionaries and work ceaselessly on streamlining and perfecting his neat, concise and poetic use of English. I notice in his lecturing an aspect I had observed previously in various interviews, DVD commentaries, etc. He seems to cultivate a “word of the day” approach to English in which he repeats a phrase or a certain word he likes many times within a short period: “Wild. Repulsive. Strange. Debased…” The combination of foreign accent, clear and precise pronunciation, and instant calling up of a unique personal vocabulary contributes to his mesmerizing and enigmatic persona. Listening to him, one could forget to eat and if he spoke for four days straight the listener would starve himself, forgetting the basic needs of sleep and food; such things would become irrelevant. The magnetic quality of his personality defies description; his natural charisma and depth of knowledge seems an endless font. He is truly a sage, despite his proclaimed aversion to all forms of shamanism.

“You can't be run over easily if you're filming with your back against the wall.”

“Early silent films were done in an alphabet everyone could understand.”

“The dominant eye sees largely in 2D. The other eye sees in peripheral 3D. In crisis, the eyes jump to 3D, but it is not the way we normally see the world. Our eyes are not trained and not ready to see in 3D all the time. 3D vision is only the norm for, say, basketball players. 3D cinema will never replace traditional cinema the way color TV replaced black and white.”

“Rashomon was shot in black and white, mono, 3x4, very lo- fi, but it is unforgettable. Avatar was all bells and whistles and tries to have so much soul, but it is empty. The only thing I remember about the story is its repulsiveness. All new age, yoga…”

On finding the focus of a shot, Werner advised, “If there is one monk left praying out of 400,000, that man is serious.”

“Filmmaking is always ruthless. Film knows no mercy."

“My projects are like a home invasion. You wake up in the middle of the night and four ideas have broken into your mind.”

While filming at the shrine of some Mayan god in Guatemala, Herzog was attacked by an angry pilgrim. Werner insisted he had a “natural right to document the subject” even if he was unwelcome.

Herzog’s second film is still unpublished. It was shot in Argentina and one scenario featured a gang of criminal children dragging a rooster through the streets. “They became murderous” so he made a moral decision not to release the film.

“Pura Vida, pure raw life, is often not filmed or is left on the editing room floor.”

“Do things in documentaries that are beyond the facts!”

“When traveling on foot, never take a movie camera but scribble notes. Separate real raw existence from filmmaking. However, I do read Landscapes better with binoculars.”

One never knew where Werner would go next in his wild acrobatic musings. He spoke of DaVinci and of his own capturing of a “Cathedral of Stalagmites” in the cave documentary and also of the obscure Dutch painter Hercules Seghers from the 1600s, who created “wild, bold, completely original landscapes” and ended up an insane impoverished alcoholic: “His prints were used to wrap sandwiches and were thrown away. Rembrandt was his only supporter and once added figures to one of his bizarre landscapes. ‘I will do these Landscapes till they take me out feet first!’” He spoke of the “completely invented landscape” of the German painting The Battle of Alexander and insisted that the “Pure invention of Landscape” should apply to cinema as well.

“Even if only five people want to see your film. it is worth doing.”

“Thinking conceptually comes from reading mostly. Read, read, read!”

“Keep control of your set. If you can't work with a key crew member one of you has to go.”

“You have to be selective about your footage. Don't overshoot, but in nature you have to shoot until the dog does what it's supposed to do or the bird returns to its nest. You have to entice the hyena to come close in.”

Little Dieter Needs to Fly was a completely staged documentary. Werner had to shoot Dieter telling a story six times before he included all the details Herzog wanted. It was written and rehearsed like a feature film. “You have to stage events for drama and move beyond what is found in nature.”

Herzog does not like to portray “the harm of the defenseless”: Rape, hurting children, etc. “It is not ever necessary.” It would be silly to do a reenactment of torture; interview the victims instead. He has found several cases of people who lost their speech due to trauma.

“Empty hearts and blind armed stupidity is the most dangerous of combinations.”

He railed against “the institutionalized cowardice of the industry” and “the Culture of Complaint. Even Francis Ford Coppola and other big Hollywood directors complain all the time. It is unproductive.”

Jonathan Caouette's Tarnation, a film Herzog and I both admire, was made for a mere $321, although the music rights cost a quarter of a million.

“Throw intelligence and flexibility at problems, not money. In Hollywood they throw money out the window as a ritual of power.”

“You can make a film for very little money, but you have to do it! There is no longer any excuse.”

“Perseverance: That’s where the Gods dwell.”

“I come without storyboards, which are the the instruments of cowards.”

Be ready to take over as camera operator when necessary. This requires lots of physical training. Elbow solidly into the torso, move the entire body with the camera, not just the wrist. Train your body to be a tripod. “I like these kind of men who have this physicality and strength and sense of time.”

Prepare shots in reverse order: Start with the endpoint and move out to the start position; this is a great way to solve problems.

Plan movement of camera based on dialogue and how it should move in the scene. When asked how many shots in a particular scene say, “I have no idea.” Herzog doesn't believe in “Coverage”: “Shoot what you need. Don't allow a “video village” on set. Watch the dailies but don't have the false security of always having screens around; it always looks bad and makes you waste time shooting needlessly, and what looks great turns out not to work in editing. Don't allow the cinematographer to use the viewfinder; he needs to know how a 24 mm lens sees without the aid of such tools.”

“How to establish the inner flow of the film is more difficult than the mechanics. Flow, balance, tempo cannot be taught.”

That first day, I had lunch with Laurie Kindiak, a rather fascinating young woman. She and her husband both work in the CGI field and on Disney’s video games, so I mentioned my friend Tony Bratton in Austin who has been at work on a top-secret gaming project for Uncle Walt’s “Original Disney” franchise featuring Waldo the Rabbit. Although Laurie lives and works in Canada and does not know Tony personally, they in a sense work together and she sees his name on corporate emails, etc. She recently returned from a trip to Burma that changed her life. While there, she had been assigned a government “sponsor” who followed her everywhere. She frequented a restaurant where she struck up a friendship with the husband and wife owners. Before she left the country, they had both disappeared and their business had been shuttered. Another woman agreed to put her up in her home but refused to put up her “guardian.” She is not sure what happened to this woman but it gradually dawned on her that every person she was in contact with, every person that showed her kindness, was in danger of being killed or “disappeared” by the army for talking to her. She had probably, unbeknownst to her, been responsible for the deaths of many of the Burmese friends she had made and would continue to endanger the lives of anyone whose path she had crossed there. Very chilling. Her dilemma now was that she felt compelled to tell the world about the situation and to go back there and make a documentary about it; but how to do this without causing more death? I told Laurie I would be most willing to help her with such a film, that I had always wanted to visit Burma (perhaps a death wish on my own part) and that I actually needed to go there for my own documentary. She promised to be in touch if the project went through. One of the problems with making a film there is that it is impossible for average-sized North Americans to travel covertly due to the diminutive stature of the Burmese people.

“How much realism do you want in your documentary? A tree or a stream might talk to you. You must be open to all possibilities.”

After lunch and much excited discussion with my fellow Rogues, Werner was joined by his longtime editor Joe Bini for more wild free-floating discussion. “Rogues, please, sit down.” Herzog and Bini keep detailed notebooks of the entire editing process, creative journals that are artworks in their own right. Bini first worked with Werner on Little Dieter and had recently edited Herzog’s 3D cave film in a mere four days. They have made a total of around 20 films together. Bini had no interest in documentaries before seeing a dream sequence included in one of Herzog’s “non-fiction” works. Working on Dieter, Bini observed that Werner actually scripted the protagonist’s testimony. Werner chimed in, “You must think of documentaries in terms of scenes; It is a movie! Don’t just gather interviews, you have to direct the film, it must be structured methodically.” Observing that in Michelangelo’s The Pieta Jesus is 33 while his mother Mary is a girl of 17 (Medici had insisted the Virgin be modeled on his fiancée), Werner insisted “Everything is allowed; facts don’t matter. Do you have to follow the rules? No, you do not!”

There was more talk of the strange forms of wildlife that pervade the cinema of Herzog, in particular the Albino Alligator: “There are only 20 in the world. They try to morph into their own doppelgängers. What did people see back then? How would a crocodile see?”

On Cave of Forgotten Dreams, Bini observed that Herzog actually included a completely invented character, portrayed by an actor speaking scripted lines. This was a supposed “perfume expert” who looks for original exotic scents at paleolithic sites, basically sniffing about caves for whiffs of decayed bears, carrion, torches, etc. Herzog viewed the scene as “an engaged human moment leading into an eight-minute montage of paintings. It is not easy to create this sense of mystery, of curiosity, of Alice in Wonderland.”

“The documentarian is not a voyeur; he is a participant. The director must shape, must articulate. But the inarticulate can be sublime.”

His is a cinema of “personal fascinations,” but with stricture and restraint. “The Zorn’s lemma mathematical axiom and the birth of children are fascinating subjects but they are not cinematic. I fainted during my son’s birth. Shit, it is not beautiful, it is violent! It will turn you off to your wife for a whole year.”

“The filmmaker, not the documentary’s subject, is the crafter of the story. The subject may have some very stupid ideas about storytelling. Go as WILD as it gets with storytelling! Channel the obscene joy of Rabelais. The documentarian is not a mutant surveillance camera. Forget all the shit you hear in film school.”

When I identified myself as a film professor, Werner grinned and said, “That is alright. You are welcome anyway.”

Discussing Cave of Forgotten Dreams, Bini and Herzog spoke of the discovery of the Venus of Hohle Fels and the unearthing of a “high-tech ivory flute” that was over 30,000 years old, as well as another ancient flute made from badger bones. The same prehistoric person with a crooked little finger made a number of palm prints in the cave, leaving “a piece of their individual identity” that exists all these millennia later. Herzog also saw “science-fiction imagery” in the caverns, “Something completely strange and not of this planet.” The pair revealed that much of the film’s footage was shot on “a camera the size of a matchbook” and that the quality was “terrible” but “it didn’t matter” and that this was the way Werner’s hero Jacques Cousteau would have shot it. Philosophical ramblings and questionings were interspersed with the footage of the cave paintings (some of which were created thousands of years apart). Natural arches near the cave suggested that “30,000 years ago, people had a sense of operatic staging and the shadow dancing tradition.” Furthermore, “We were courageous enough to show Swing Time with Fred Astaire in relation to 30,000 year old cave paintings!”

“There is no difference between the spirit and the physical world. The Natural is the Supernatural. We should be called Homo Spiritus rather than Homo Sapiens.”

“Ecstatic Truth is when we step outside of our bodies and experience something we will never forget!”

“Editing can now be done as fast as we can think.”

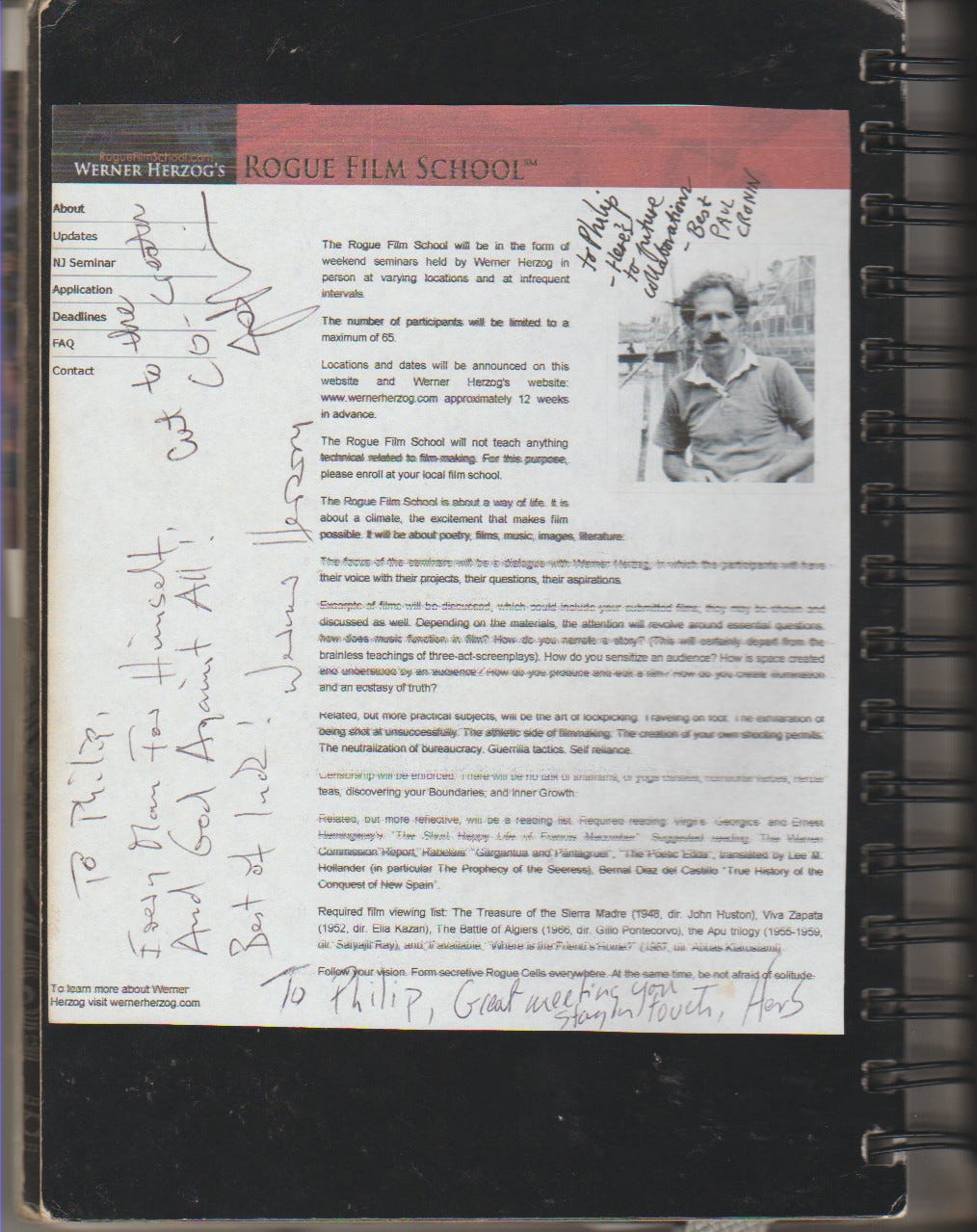

During a short afternoon break, I was bold enough to approach my hero Werner Herzog and to show him this journal I had been keeping. One of the first dramatic affinities I felt with the great director was the glimpse he offered of his tiny journals in My Best Fiend, so similar to my own in many ways (My very earliest fascination with Herzog began with the shock of seeing Aguirre, The Wrath of God as a seven year-old boy in Tehran, Iran, 1974). I was bothered that so many of my fellow students had not bothered to study the assigned readings and films for the course given this incredible opportunity, a filmmaker’s equivalent to sitting at the feet of Aristotle in ancient Greece. So as Werner lingered in the hall and made himself available to the students at the break, I approached him. “Werner,” I stammered, “I know how dear journals are to you and I’d like to show you the one I’ve been keeping for your course. Here are the preliminary notes based on your reading and viewing lists, and these are my lecture notes thus far…”, just so he knew. someone cared enough to do the prep work and that the seminar was not taken lightly by me. He took the journal from my hand and began studying it. “You have really been hard at work. I love these kind of journals. It is quite remarkable, Philip.” Werner and Bini had discussed their editing journals a bit and had held some of them up for the students during the lecture. Now, Werner asked me, “Do you want to see my editing journal?” I said that would be an honor and he responded, “I will give it to you when we go back inside.” I told him it was a great honor to be there with him and that, as a lecturer myself, I couldn’t fathom where he got his energy.

“You see, I have to give it my all. Many people here have come from very far away at great sacrifice and expense, and I must give them everything. At the end, they will have to take me away on a stretcher!”

I said that I hoped that wouldn’t be the case and he put his large Bavarian paw on my shoulder, smiled his famous demented grin and said, “I am joking.” As he continued to peruse my journal, I told him it would be wonderful if he would write something in it. He sat down on a bench in the hall to lay pen to paper properly, ruminated a few moments, then wrote something slowly and carefully before rising and showing me the inscription.

“This is an expression by Mario de Andrade, but I have adopted it as my own: Every man for himself and God against all.”

I assured him I was aware of the provenance of the quote and that he had taken it as his personal motto. Joe Bini strolled over about this time and Werner passed my journal to him, so Joe signed it as well: “Cut to the Co-Creator.” He then handed the book to Paul Cronin, who inscribed it, “To Philip, Here’s to future collaborations.” It was some strange sort of journal ritual. Paul had earlier observed my journal during lecture and had remarked, “That’s some fine script!”

When we returned to the classroom, I was now in proud possession of the editing journal, which Werner handed me as I entered. I was flabbergasted. I had had precious little time to survey the riches of the editing journal between my own furious scribblings before Werner began wrapping up for the day. I noticed that that there were copious notes on both the “Albino Alligator” and the “Radioactive Alligator” in the journal and countless other entries all in Herzog’s sure, steady hand. About that time, the topic of the editing journals had come up again and he scanned the classroom for me then said, “Philip, do you have this journal?” I walked proudly to the front of the room and handed it to him with a bit of a flourish. He held it up again so that my fellow Rogues might see it. I felt I had held some sort of grail in my hands.

Then, Werner and Bini were finally getting around to discussing editing proper. At least for the moment. Grizzly Man was edited in a mere nine days. Werner praised Bini’s attention to detail in the cutting room: “It takes a real filmmaker to realize that some unobtrusive piece of footage is mysterious and powerful. Oh yes, find more foxes!” The footage was assembled both to indict the “Disney-fication of Nature” and to reveal Timothy Treadwell’s human qualities. “The wafting of grass in the wind” demanded inclusion: “Be aware of Mysterious footage that demands to be in the film whether it seems relevant or not. Learn to understand the value of your own footage. Avoid the straightforward approach. You have to have the wonder and awe of a child seeing a movie.”

Werner once delivered a project for German television that was intentionally two seconds under the strict running time requirements, just to assert his autonomy. With Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans, a reimagining of the notorious 1992 Abel Ferrara film which star Nicolas Cage insisted be directed by Werner, Herzog and Bini waited to include the bizarre footage of iguanas in the working cut until the last minute. By that point, the studio execs had no time to do anything about it. “Using Rogue Tactics, I saved it from the machinery of Hollywood,” Werner laughed, “To show that I am not docile,”

When Werner and Joe opened up the floor for questions and comments, I was called on and told them that one of the things I stress to my own film students is that “documentary objective truth” is a myth and that docs are as highly manufactured as “fictional” films; this goes all the way back at least to Flaherty. “They are highly editorialized works, not truths handed down to man from God,” I proclaimed. Furthermore, I continued, Herzog and Bini should be hailed for helping explode this myth by aggressively using staged scenarios and other fictional elements in their documentaries without apology or explanation. Werner smiled and nodded vigorously and whispered, “Yes, that’s RIGHT!” Bini responded, “You really nailed it there. If you’re wanting objective truth, then you shouldn’t pick up a camera to begin with.” Werner followed up: “Yes, filmmakers are not surveillance cameras in the supermarket. You should tell your students not to be a mutant surveillance camera.” I fared much better in my exchange with the two men than did the next student to offer his thoughts. Joe Bini listened carefully to the kid’s stilted monologue before responding: “I have no idea what statement you are trying to make and it sounds like a bunch of nonsense.”

“The Poet must not avert his eyes!”

“Those who read own the world. Those who watch television lose it.”

After Bini left to fly out to London on film business, Herzog next steered the discussion toward his love/hate relationship with contemporary popular culture. “Mainstream audiences have very strange rules. Everything is aimed at the least common denominator. Stallone is always ready to show his muscles and show that he is ready to shoot the Gook!” He declared Wrestlemania to be “a wonderful, vulgar version of ancient Greek drama” with the “universal theme of good versus evil.” However, the raw, uncouth choreographed fighting is consistently interrupted by commercials. “Thousands of years of storytelling have been destroyed by television commercials.” For Werner’s money, “The Anna-Nicole Smith show is the ultimate vulgarity.”

Werner announced that another of his longtime collaborators, Herb Golder, would be joining us tomorrow. He ended day one of the Rogue Film School with the following closing remarks:

“The notion of making the world a better place is suspicious. Yes, you should take a stand and fight. But the last thing I want to see is you drifting into some vague, stupid, and debased New Age philosophy. We are a minority who have an ability for storytelling. We are making movies and we are going to go WILD!”

Encounters at the End of the World…

A truly incredible encounter: After dinner with the Rogues in the hotel restaurant (where the kind staff let me in on the “secret menu” of cheaper fare), I walked past the seminar room on my way to the elevator, and there in the empty corridor sat Werner Herzog and Paul Cronin on a couch looking at books and discussing them. Paul and I throughout the day had found opportunities to have some brief chats. I paused ever so briefly near them, then thinking better of it was prepared to go on up to my room, but Paul nodded to me and said, “Please. Join us.” And so…I plopped down next to Werner in the available space. They were looking at Paul's copy of The Warren Commission Report, an old hardback edition that, unlike my copy, actually had photographs and other illustrations. The evening before when Werner had first addressed his Rogue cell collectively, he had asked who had read it and I may very well have been the only one who raised his hand. He had described it then as “a brilliant exercise in logic” and cursed all the Kennedy conspiracy writers and directors like Oliver Stone who he felt had never bothered to read the definitive study of the events in Dallas. “No one ever reads this book and it is so brilliant.. There are 400 Pages giving evidence that proves this weapon fired this particular bullet…” Werner had gone on to note how the book could provide the source for a great crime thriller, an observation I had also made as I read it. Now he made a few similar comments and I told Paul what a great old copy he had found as I thumbed through it, listening intently to whatever the two men had to say on the subject. I commented on how cinematic I found the first portion of the book; that it was written in a style suggesting the cross-cutting of film editing as we get the various perspectives of different characters on the same events, a bit like Kurosawa’s Rashomon. I agreed with Herzog that it was a brilliant piece of literature and wondered allowed why it had never been the basis of a feature film.

Werner and Paul were both pretty amused by my yarn about how growing up in the Fort Worth-Dallas area, it seemed that every person of the older generation including uncles, grandfathers, family friends, etc., claimed to have some connection to the Kennedy assassination. My own grandfather was part of Jack Ruby’s inner circle while the father of my best friend claimed to have played some small role in the shadowy events of November 22, 1963, although he would never disclose the specifics of his involvement. He also claimed to own the hat Ruby was wearing when he shot Oswald. To this day I continue to meet people who claim to have lived “just down the street” from Oswald at one time or another. Every person of a certain age seems to have a personal connection to the tragic event, a kind of collective mythology has attached itself to the very culture of the North Texas Metroplex.

Werner, though obviously exhausted and bleary-eyed from a full day of “teaching”, was seemingly delighted with our conversation. He must get his stamina from the Norse gods. Paul had brought his copies of the entire reading list to the seminar so we next turned to Diaz's Conquest of New Spain. Paul had a later edition of the same Penguin Classics copy I was reading and Werner pointed out how abridged the Penguin version was. I mentioned that in the editor's introduction, he does state that he cut the volume down by half but he at least gives us synopsis of of the information he has elided, which is often simply long lists of what types of horses were loaded onto the ships on certain dates, etc. Werner got very excited suddenly and informed us that these were precisely the best parts of the book: “The great love of the horses, the breeding, the naming…” I interjected that it sounded very much like Virgil's Georgics and Werner nodded vigorously before continuing, “Yes, he writes marvelously in these passages of horses, like the one who was nothing more than a lazy bum but that on the battlefield he had no equal. Marvelous descriptions of these horses and their distinct personalities.”

“Philip,” said Paul, holding up a beautiful old edition of The Poetic Edda, “Did you know this was actually published in your hometown?” I was indeed aware that the tome had been published by UT Press, at least my own newer copy was. Paul, an Englishman attending the PHD program at Columbia in New York City and teaching there in addition to his work as a documentarian and historian, was very curious about Austin and we begin to to talk about the city. Paul states that he has a dream of driving from West Virginia to Texas and really seeing the South; I inform him how often I had made this trip while I was in the service. Werner and Paul seemed to marvel at my driving for several days across the nation; Europeans often seem astonished by the marathon driving habits of Americans. Paul and I agreed we would make a cross-country trip together someday and I could show him some sites. We discuss Werner’s belief that the best of America comes from the heartland, either the Deep South- Flannery O'Connor, William Faulkner- or the Midwest- Ernest Hemingway and Bob Dylan. Paul argues that he himself is technically a Midwesterner since his grandfather was from Wyoming.

I turn the subject of the Midwest back to Werner’s work, telling him that the Wisconsin-set Stroszek is my personal favorite of his films, although I can't say precisely why. “By the way,” I continued, “I'm showing my students Kaspar Hauser next week.” This last was prompted I believe by Paul's assertion that The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser was in fact Herzog’s best film. Although I was unsure how Werner might feel about such things, I wanted him to know that Stroszek wasn't simply my favorite of his films, it was also a primary influence on my feature film Welldigger and I had actually stolen shots from his film in direct mimicry of it. I was fairly certain he would not condone filmmaking practices such as homage since he strives for a cinema of never-before-seen images. Thankfully, however, he seemed rather flattered, telling me, “You should steal often and from the best. I greatly admire any great and honest thief.”

I asked him if he has seen his friend Harmony Korine's new film. “The Trash Humpers, yes? No, I have not. I don't know that I have seen a movie this year.” Paul reminds Werner that he was recently a judge at the Berlin Film Festival where he saw 20 films in a week. Herzog: “Oh, that is right. I did see those films.” Paul: “They obviously made quite an impression on you.” Werner then went on at length about the festival jury's battle over awarding Roman Polanski's The Reader a prize and how his fellow judges were afraid of the message it might send to give the prize to the controversial director. Werner had pleaded, “So if a mediocre film from Haiti had been featured we would have awarded it the prize because the world is in sympathy with Haiti this moment? Fuck that. We give the award to Roman because of his artistic accomplishment, for his masterful direction. He has earned the award and let's just give it to him.” I told him that his opinion probably had more weight than that of the other jury members since he had inarguably made some of the greatest films of all time. He looked me deep in the eyes and quietly and humbly said “Thank you, Philip.”

Werner's ears certainly perked up when I talked about growing up in Tehran, Iran and about Dad barely getting out before the hostages were taken. Of course, an Abbas Kiarostami film was on the Rogue Film School viewing list, so Herzog had at least a passing interest in Iran. As it turned out, Paul is currently doing extensive research for a book on the acclaimed Iranian director and was actually in attendance at the Marrakech Film Festival in 2005 when Martin Scorsese presented the Lifetime Achievement Award to Kiarostami. It seems likely that Paul turned Werner on to the cinema of Kiarostami. As for myself, certainly Iran and cinema are two forces that have shaped my life as much as any other.

The three of us probably set together for 40 minutes or so and we talked “wildly” about profound and interesting things. I told Werner what an honor it was to be studying with him and how much I appreciated his willingness to engage with the students and share his knowledge and to be available to them 100%, not slipping out a back door quickly as soon as his lecture was over. The fact that he was so present exceeded my wildest expectations of what this thing would be. Obviously this current surreal situation in the corridor was at the front of my mind and I was struggling to wrap my mind around it the whole time I sat there with them, the fact that I was sitting on a couch in an empty hotel corridor in New Jersey discussing books, films and life with the filmmaking giant I admired above all others.

Herzog is clearly exhausted and flagging has now slipped into a yawning cycle but he nevertheless continues to amaze us with stories and anecdotes. The spirit is willing but the flesh is weak. I marvel that the three of us have sat here undisturbed for so long and that these two great men with their long history together had invited into their world and for this I am truly grateful. “I am so sorry to be doing this yawning. I am very, very tired and do not know why I'm so tired. All day during the breaks I come to this couch but I only rest my shins against it as I stand and talk to people. Now I am sitting on it and it is the most wonderful couch and I am way too comfortable. But you know, I think then that it is time for me to go, Paul and Philip. Lena will be arriving soon if she is not already waiting for me upstairs. See you in the morning.” Werner stood and shook our hands, chatted with us a moment longer, and went on his way to meet his wife.

Paul and I stayed on the couch a while longer and continued our conversation. We marveled over the great Herzog; how this 67 year-old German had more energy and vitality than most American teenagers. His stamina is incredible. While I am completely wiped out after lecturing for three hours, Werner had stood and spoke, showed clips and answered questions for over eight hours that day. We spoke of Werner’s honesty and lack of pretension, his authenticity, his genius. Paul also brought up the fact that Werner's brother Lucki Stipetic had essentially managed Herzog's career from the beginning and had had a whole lot to do with Herzog’s success and longevity; Lucki’s wise business acumen and his role in the making of “Werner Herzog” cannot be overstated. Paul very kindly reassured me that my presence had in no way preempted their conversation and that I wasn’t an interloper. “You're interesting and I know Werner thinks that as well. That's why we invited you over.” He noted how Werner’s face had lit up and how excited he got when I mentioned my many road trips around America and how this man who has traveled to some of the most remote and dangerous places on Earth found this comparably mundane odyssey so remarkable. Paul stated that “This is what Werner loves, you see? This is what he does. Talking to cool people and looking at books together, good conversations about adventures and books. And if you have that ability you're welcome into his world.” I thanked him for welcoming me into the realm.

Paul spoke of Werner’s loyalty and honesty. “It’s quite amazing that once he lets you in, you’re a dear friend for life.” Paul was a young, relatively unknown film scholar, historian and fan when he first contacted Herzog about putting together a book of interviews with him. Werner was initially quite reluctant and Paul really had to convince him, but all these years later they remain close friends, with Paul helping out with the Rogue Film School and compiling material for a new edition of Herzog on Herzog. He was recently invited to attend the opening of Lena’s latest photography exhibit with the couple.

Paul and I have a remarkable amount in common. Both of us are working on a dual book and film project about the same subject, so we are also both doing extensive research on the counterculture of the 1960s. Paul is also arguably the leading expert on one of my favorite films Medium Cool: He's interviewed most the people involved with the film and even the politicians of the era. Every new subject we discussed seemed to mine deep connections between us; almost long lost brothers in a sense. After about an hour, Paul’s girlfriend arrived to pick him up; they were having dinner at her parents’ home in New Jersey. She is a successful lawyer who, like Paul, enjoys the finer things.

When Werner had risen from the couch to leave Paul and I, he had wondered aloud why so many students still hadn’t uttered a single word in class. I told him that there was so much I wanted to say and ask about, but that I was concerned about monopolizing too much class time. Werner responded:

“You should not worry about that, because you are always bringing up the essentials, which is what we need. I always look for you when we move onto a new subject because of this. And today I looked around for you and saw you had moved to the back and were crouched there writing, and I said, There he is, concocting something…”

To be continued…

Extremely interesting. Made me wish I had been there with you.

Loved this article!!