Wishing you all a very happy and peaceful Thanksgiving. No matter who you spend time with this holiday season, love the ones you’re with.

9. “When the world stops turning, Then I'm going back Home…”

You also traveled back home to Texas on two occasions. The long uncomfortable flight was often worth it because the movies that were played on the plane were much newer than the ones playing in Iran; you were able to see films like All the President’s Men with Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford and Three Days of the Condor with Redford and Faye Dunaway while they were still in theaters as you made your way back. These returns were very exciting, ecstatic even. “Home,” the US, had attained a mythical status for you, a symbolic lost paradise that you feared might disappear in your absence or change into something unrecognizable. Reuniting with your extended family was sheer joy as was the impossible comfort of you grandparents’ home. These trips also allowed you to pick up the latest comics, see movies you had only dreamed about, and catch up on your favorite television programs, many of which had still not been exported to Iran. These included a half dozen gritty crime dramas and cop shows whose titles were always simply the detective protagonists’ names: Baretta (Robert Blake), Cannon (William Conrad), Colombo (Peter Falk), Kojak (Telly Savalas), and Starsky & Hutch (Paul Michael Glaser and David Soul, who also had a hit song at the time). Only The Rockford Files with James Garner slightly deviated from this strict nomenclature. You also enjoyed the golden age of socially conscious sitcoms produced by a combination of Norman Lear and James L. Brooks, intelligent shows that tackled tough adult themes with barbed but humorous social criticism. Network television taught you something of American diversity and inequality while making you laugh through episodes of The Mary Tyler Moore Show (such a great cast of characters that three of them got their own spin-off series), All in the Family (Archie Bunker was brilliant, especially when he stuck it to his annoying bleeding heart pseudo-intellectual hippy son-in-law), Good Times (JJ was cool, Thelma was hot, and John Amos was a black version of your own father), The Jeffersons (the least socially conscious of the lot and probably the funniest), Maude (Adrienne Barbeau was your dreamgirl), Rhoda (and so was Valerie Harper), and Sanford & Son (while you loved Redd Foxx, you insisted that Demond Wilson was a great thespian and should be hailed as the Black Brando; no one got the joke). For pure escapism, there was The Six Million Dollar Man, the new Planet of the Apes TV series, reruns of Star Trek, The Rifleman, Bewitched, Gilligan’s Island, I Dream of Jeannie (Barbara Eden, you have seduced my soul…), My Favorite Martian, The Dick Van Dyke Show, I Love Lucy, Batman, and The Carol Burnett Show. You were fascinated by the undersea exploits of Jacques Cousteau and were also quite a fan of The Partridge Family; the music was excellent, David Cassidy was cool, and you loved the way the show subverted hippy culture and presented the musical family as hip and slightly psychedelic but also clean, wholesome, and always loyal to one another. Traditional family values, hippy pop music, and lots of positive vibes in a nice neat package. The Brady Bunch had a similar essence, but lacked the groovy music. Period family dramas like The Waltons and Little House on the Prairie also appealed to you and you also stayed up late for The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, hoping to see your favorite stars including comedians like Rodney Dangerfield. No matter the household, the TV was always on in the evenings in the American 1970s.

Drive-in movies had been a big part of family life before moving to Iran and the tradition was revived each visit home. There were at least a dozen such cinematic wonderlands in the Fort Worth area, but the Belknap with its two-story tall street art depicting a buffalo kicking a football at the entrance remained the family favorite. The drive-ins were the place to see the low-budget exploitation and violent action films you all enjoyed (with the possible exception of Mom, who kept quiet about it). You saw films there like John Milius’ Evel Kneivel with George Hamilton, Walking Tall Parts 1 and 2 with Joe Don Baker and Bo Svenson respectively, and Rolling Thunder with William Devane and Tommy Lee Jones.

But there was nothing quite like seeing the new movies you had previously only dreamt about when you came back home. You almost passed out with anticipation on the way to finally see Steven Spielberg’s Jaws. The film more than lived up to everything you had imagined; in fact it exceeded all expectations. You had expected a scary and well-executed monster movie, but it was so much more. The writing and characterizations were some of the best you had ever seen onscreen and you were spellbound by the performances of the three central actors (Roy Scheider, Robert Shaw, Richard Dreyfuss), each man so macho and shrewd in his own distinctive way. It was such an accomplished movie and so very grown up; you could not imagine ever seeing a better one. Another highly anticipated film was Rocky, which featured a droopy-eyed, muscle-bound new star named Sylvester Stallone. As a boxing fan and fervent admirer of Muhammad Ali, you had waited an excruciatingly long time to see the acclaimed sports saga. You had Rocky posters on your bedroom wall and a little paperback book written by Stallone himself called The Rocky Scrapbook featuring lots of stills from the film and a commentary on its inception and production. You also owned an Iranian bootleg cassette of the soundtrack album which never failed to excite you. Like Jaws, the very adult sophistication of the film, the amazing performances by Stallone, Burgess Meredith, Burt Young, Talia Shire, Carl Weathers, and Joe Spinnell, and its realist, almost documentary style ensured the film more than lived up to your expectations (This would not exactly be the case when you finally saw Star Wars). It also was always a pleasure to discover exciting actors you weren’t yet familiar with. On your last visit home before moving back for good, you saw a great Robert Redford heist film called The Hot Rock and also an impressive disaster flick called Roller Coaster; both featured very interesting performances by some cool cat named George Segal.

10. “The Sharif don’t like it. Rock the Casbah, Rock the Casbah…”

Despite your many adventures out into the wider wilder world, the shape of your early life was largely interior, a jumbled collection of eclectic obsessions which you pursued in solitary, monk-like devotion. Your bedroom was your mountaintop hermitage in these pursuits. You were a child of the American Seventies by proxy, a wild colonial boy living in an insular community of Americans and Brits in the Middle East. Music, movies and books became a kind of ticket home. You lived largely in your head, and art and popular culture were your true friends and lovers.

In addition to the American/British TV station, there was also an AM radio station that broadcast the pop hits of the 1970s to the English-speaking denizens of Tehran. This station was often tuned into on the family’s small transistor radio while at home and in the red Citroen’s primitive system on the road, and it was also carried over various speakers throughout the Pars American Club, acting as a soundtrack to much of your childhood. Some of your favorite radio pop of the period included “Dancing Queen” by Abba, “American Pie” by Don McLean, “Fooled Around and Fell in Love” by Elvin Bishop, “Alone Again” (Naturally) by Gilbert O’Sullivan, “Angie” and “Wild Horses” by the Rolling Stones, “Season in the Sun” by Terry Jacks, “Bennie and the Jets,” “Honky Cat,” “Crocodile Rock” and “Someone Saved My Life Tonight” by Elton John, “The Air that I Breathe” by The Hollies, “Jive Talkin’” and “Nights on Broadway” by The Bee Gees, “Kung Fu Fighting” by Carl Davis, “Black Superman Muhammad Ali” by Jimmy Wakelin, “Why Can’t We Be Friends” by War, “Magic” by Pilot, “School’s Out,” “Billion Dollar Babies,” “Only Women Bleed, “I Never Cry,” and “You and Me” by Alice Cooper, “I’m Your Boogie Man” by KC & The Sunshine Band, “Killer Queen” and “Bohemian Rhapsody” by Queen, “The Rockford Files Theme” by Mike Post, “The Boys Are Back in Town” by Thin Lizzy, “Live and Let Die” by Wings, “Tonight’s the Night” by Rod Stewart, “Rich Girl” by Hall & Oates, “Rebel Rebel,” “Young Americans” “Fame” and “Golden Years” by David Bowie, “Walk This Way” and “Sweet Emotion” by Aerosmith, “New Kid in Town” by The Eagles, “Night Moves” by Bob Seger, “Rock and Roll” and “Black Dog” by Led Zeppelin, and “Because the Night” by Patti Smith Group. There were also a number of Farsi versions of hit songs which you would hear out in town; the Iranian interpretation of The Captain and Tennille’s “Love Will Keep Us Together” was especially catchy and well-executed.

Despite a fear of and contempt for hippies and the drug culture which tended toward an ideology that would come to be called Straightedge, you were mad for rock music in all its forms. Your parents had played vinyl records throughout your childhood as a sort of evening ritual, Music was key to life as far as you were concerned. Somehow you developed the mysterious thing called Taste. As memory serves, your earliest attempt at writing was, rather strangely, a poem about a dying woman from her grieving husband’s point of view, which you set to music by humming a very basic tune to accompany it until you had memorized it and could sing it.

You were “somewhere on the spectrum” as they would come to call it, and possessed a unique ability to enter into distant realms of fancy and tune out all else. There was a strange sense of otherworldly alchemy, of God looking on as you created alternate worlds, whether absorbed in listening to your cassette tapes and visualizing the songs, forging intense epic dramas with your toys, drawing comic strips, or writing stories. Years later, you would experience this feeling again and realize you had been making films without a camera back then. Your ability to completely shut out the world around you did not sit well with your father who would repeatedly call your name until finally resorting to yelling it, which shocked you out of your fanciful trance like a diver with the bends. Yet you always heard what interested you. One day, you were playing with toys in your bedroom while your parents were talking quietly in the living room. You could barely even hear the low murmur of their voices until suddenly the name Elvis Presley was mentioned. You put your toys down and strolled casually into the living room. Your parents stopped talking and looked at you expectantly. “Excuse me,” you said in your best young fancypants voice, “But did one of you just say something about Elvis?” This did not sit well with your father, who threw down his newspaper and exploded. “Damn it to hell, son! I can be right next to you and call your name a million times and you don’t hear me. But if I’m in another room and whisper the word ‘Elvis’ you somehow hear loud and clear!” You retreated back to your sanctuary head down in shame. Later that night, Dad came to your door and tossed a newspaper with a picture of a transformed King onto your bed. “Rock & Rolly Poly,” the caption read. “He’s gotten quite fat,” Dad murmured as he walked back down the hall.

Around the same period, you bore witness to Alice Cooper performing “Go to Hell” and “I Never Cry” on a broadcast awards show and fell madly under the spell of the singer who embodied your dual passions for classic horror films and hard rock. You had a tiny cassette player in your room and spent hours listening to tapes with your head pressed to the speaker. Your father took you to strange bootleg tape markets and let you browse their offerings; pirated tapes with Xeroxed covers that combined artists like Alice Cooper with Rod Stewart, the Bee Gees and Gordon Lightfoot, onto a single cassette. Two full albums never quite fit onto the cassettes so they would mysteriously end in the middle of a song and you would wonder how the rest of the song went. Sometimes you wondered which artist was performing a particular song, or if a mistake had been made and the wrong artists listed on the cover. Could that really be Alice Cooper buried under the disco strains of a song called “No More Love at your Convenience”? On which track did the old Rolling Stones’ record end and the accompanying Yardbirds album begin? And speaking of the Stones, one of the last of these Iranian bootleg tapes you picked up before leaving Iran was their 1978 punk era album Some Girls, filled out on Side B with some Iranian muso’s idea of “The Best of: The Rolling Stones.”

Your folks drove you to the mountains for skiing to a California sunshine soundtrack of Brian Jones-era Stones, Neil Diamond’s “I Am I Said,” and “Rainy Day Women” by Bob Dylan along with Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, Jimmy Reed, Charlie Rich, Johnny Cash, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Janis Joplin, Tom Jones, Ray Charles, Kris Kristofferson, Demis Roussos, Otis Redding, The Mamas and The Papas, Johnny Rivers, Rod Stewart, The Eagles, and John Denver, all via the red Citroen’s primitive tape deck. The double cassette set of the Beach Boys’ Endless Summer was always a crowd-pleaser on such trips, while Louis, worlds beyond the entire family in terms of musical sophistication and much else, demonstrated his exquisite taste by offering up his cassettes of Elton John and Queen. Wonderful music for wonderful times. Your brother’s tapes of Elton’s Goodbye Yellow Brick Road and Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt Cowboy struck a chord deep within you and transported you to whole other worlds. The title track to the former record seemed to be a tale about moving from the childhood innocence of fairytales and dressed animals to some undetermined new phase of existence while keeping your fantastical imaginings intact. And it was so beautiful. Another of his songs, “Daniel” seemed an eerie portent of your inevitable emotional dislocation from your big brother and the difficulties of family life to come.

The music you loved also rather thrillingly terrified you at times. The opening strains of two diabolical Rolling Stones recordings never failed to send shivers down your spine. The intro to “Child of the Moon” featured a jangly psychedelic Brian Jones guitar lick followed by Charlie Watts’ drums kicking in, but buried deep beneath was a swirl of yelling voices that evoked some drunken domestic dispute, almost like the angry ghost of a previous recording coming through on the tape. It sent shivers down your spine but was so good. “We Love You” opened with the startling sound of doors slamming and seemed to carry over the domestic violence theme of the other song. As the two songs played out, they continued to seem imbued with a sense of malevolence, of supernatural menace. “Child of the Moon” evoked some pagan ritual sacrifice in the English countryside, while the malicious piano and ghostly group vocals of “We Love You” coalesced to create a dangerous mood of drugged out decadence and demonic conjuring. To your young and impressionable mind, these were great works of art, rife with hidden worlds to explore lurking below the surface, offering thrills and chills similar to those of a witchy horror movie.

Alice Cooper didn’t normally scare you since his horror movie schtick was somewhat childlike and wholly integral to his overtly theatrical persona which you dug. He was after all a pop star designed to appeal to weird gothic-minded, monster-loving children. However, when you bought an Iranian bootleg cassette of his 1977 album Lace and Whiskey (paired with most of a Mothers of Invention album), two of the cuts had an eerie effect on you in a manner similar to that of the early Stones recordings. “My God” with its haunted church chorale and pipe organ and strange song structure, and the aforementioned “No More Love at Your Convenience,” featuring multiple bizarre and slightly threatening voices not quite singing together while inexplicably married to a pulsing disco upbeat. Downright disturbing and ineffable. You came to believe that some of the best music was scary music, transmissions from some beautiful and terrible twisted netherland you wanted to visit often but not necessarily live in. “California Dreamin’” by The Mamas and The Papas had a similar effect on you, both terrifying and thrilling. The beautiful haunting voices sounded more like keening spirits in an Irish graveyard than a quartet of LA hippies. Beautiful, melancholy, and ghostly.

Pop music as always served as a form of sex education for young listeners and at the age of 10, you had come to love a radio hit called “Ma Baker” by a funky R&B act called Boney M. You picked up a couple of their tapes at the bootleg store and were fascinated by the Xeroxed album art featuring a shirtless virile black man dominating two nearly-naked soul sister sex slaves with a set of huge chains. You were further surprised by the X-rated lyrics and simulated sex running rampant throughout the tapes; listening to them seemed to you like what watching a pornographic film must be like. The same was true of vivid sexually explicit tracks like “Dinah Moe Hum” by the Mothers of Invention, part of whose album took up most of side 2 on your Lace and Whiskey Iranian bootleg Cooper cassette before abruptly cutting off when the tape reached its limit.

Each week at Tehran American School, one child was required to do a show and tell presentation. One morning in 1975, the teacher announced that a very posh, upper crust English boy named Peter would be doing the honors. There was a buzz around the classroom, what would this stuffy sophisticate be giving the class? Peter strode to the front of the room with extreme military bearing, holding a portable record player in both hands and an LP under one arm. He proceeded to plug the player in, removed the record from its sleeve and placed it carefully on the turntable. He gave his peers a slight bow then held up the sleeve, which featured what appeared to be a host of interconnected demonic creatures amid a purplish phantasmagoric seascape. Clearing his throat, Peter held forth thus in his best baronial Queen’s: “This is a record by a rock band from Scotland by the name of Nazareth, and the song I’m going to play for you is called ‘Don’t Go Messing with a Son of a Bitch.’” Suiting word to action, he then dropped the needle and played “Hair of the Dog”, four minutes of the hardest and most profane rock and roll you had yet heard. Your mind was blown. As the song finished and he packed up his DJ kit, Mrs. Azari started the round of applause, gleefully saying, “Thank you Peter, That was wonderful!” The kids’ love of rock music was widely encouraged by the teachers at TAS and some even allowed their young charges to listen to tapes and records while doing assignments. One funny instructor, an attractive Iranian woman, would jibe the kids by repeatedly asking “Why do you like all these silly love songs?” but she seemed to dig western pop music as much as the kids.

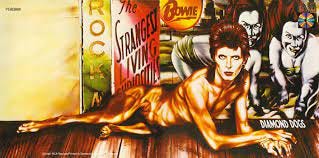

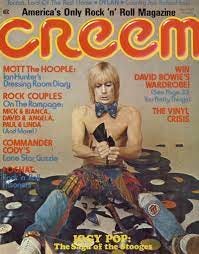

Your early babysitters in Iran included two sisters who lived in your building, one astonishingly beautiful, the other rather homely. You loved them equally. They were ultracool chicks but not hippyish in the least, more like the protopunk California girls from The Runaways. They had photospreads of pop stars all over their bedroom walls and read Creem magazine; they were light years older and very sophisticated and they turned you and your brother onto the pleasures of glam rock. The poster of David Bowie in their bedroom completely captivated your imagination; a red-haired circus freak, not only half dog and half man but seemingly half man and half woman as well, with a canine cock on proud display between his (?) doggy legs. Who was this monstrous magical creature from another world who had outdone all of Alice Cooper’s shock rock antics in a single startling image? You immediately fell in love with his music when the girls played a tape for you. It was indefinable; sometimes it seemed like radio-friendly orchestral pop, but sometimes it was more like hard rock; there was something of Dylan and The Stones about it, yet it leaned also toward funk flirting with disco at times. Mostly, it was beyond anything you had ever heard in pop music, the musical score of a weird erotic art film you were forbidden to see perhaps. It was very English but at the same time seemed to come from a galaxy far, far away; strange science fiction stories of Diamond Dogs, Jean Genies, astronauts named Major Tom forever lost in the void, and rock bands that hailed from the planet Mars. It was everything you had ever wanted from music. You immediately wrote to your grandmother begging her to send you a cassette of the album Changesonebowie as soon as possible. It was always an incredible treat to own an official American cassette release of the music you loved, complete with beautiful cover art and occasionally a foldout lyric sheet with liner notes. Not long after, you saw Bowie performing “Heroes” on TV, an early music video you would never see again. The singer was bathed in a dramatic chiaroscuro spotlight and would turn his back on the camera and embrace himself, his hands playing down his back and sides giving the appearance of a romantic engagement with a lover. It was spellbinding stuff. Your brother meanwhile fell under the spell of a new band called Kiss, who were heading up an emerging hard rock genre known as heavy metal. One of the sisters was deeply in love with Paul Stanley, who she insisted had the sexiest hairiest chest since Burt Reynolds.

One of the greatest pleasures of any boyhood is the constant exposure to the new, and there was always something different coming around the bend musically in the 1970s. The innovation and excitement, the constant transformations in the pop music of the time seemed like an inexhaustible natural resource. Browsing in an unremembered shop in 1974, you and your brother discovered a hardcover coffee table book titled Pop Today, published in London and in the English language. It was a mind-bending treasure trove devoted to the still emerging glitter rock scene, featuring stunning full-page photos of, essays on, and interviews with the likes of David Bowie, Alice Cooper, David Essex, Elton John, Queen, Roxy Music, Rod Stewart, Slade, The Osmonds, David Cassidy and many other acts you had not yet heard of. You and your brother quarreled over who would get to own it, then you each realized neither of you had enough money to purchase it. Your father stepped in, advising that if you both really wanted it so badly, you should put your allowances together, he would cover the balance, and then you could share it. In a rare joint venture, you and Louie did as he suggested, and that book became a sort of family Bible for you and your big brother for the next year.

Taking your cue from the babysitting sisters, you were soon buying rock mags like Creem, Circus, New Music Express, Rolling Stone, and Hit Parader, trying incessantly to keep up with the progressive sonic trends of Britain and the US. Creem was your favorite; the mag had a decidedly smartass music snob vibe to it while also focusing on what seemed to be a more underground, less commercial strain of rock and roll, with lots of coverage of Bowie, Cooper, and the glam rock scene. In the pages of Creem, you discovered that the long hangover of the 1960s might just finally be on its way out. Punk was creeping into your consciousness if only based on photos you saw in the magazine. There was something new and sexy, something exciting and fascinating, but also a bit terrifying about the images of Iggy Pop, The Ramones, Blondie. It wasn’t the age-old revulsion and horror you felt toward the imagery of hippy culture; more like the fear of an unknown emerging danger you had never imagined and found yourself intensely attracted to. In one issue of Creem, there was a full-page color photo of a rail-thin and very androgynous woman (presumably a heroin addict based on her appearance) named Patti Smith, who sat on the floor of a squalid New York apartment in a white undershirt with her knees pulled up under her chin, the better to fully expose her naked pink labia. It was unlike anything you had ever seen in a rock magazine or anywhere else. Another issue contained a similarly shocking full frontal nude image of another dangerous-looking apparent punk junkie, that of an extremely well-built and well-endowed Iggy Pop. When the Sex Pistols arrived soon after, the punk imagery in Creem took matters to the next level. There on the cover was a sneering, bug-eyed creature called Johnny Rotten, who seemed to be some very raggedy, pimply-faced, and highly pissed off incarnation of David Bowie. Meanwhile, his bandmate was apparently named Sid Vicious and had very real lacerations across his chest and also had a nail or something embedded in his forehead. Had the audience done this to him or were his mutilations self-inflicted? Alice Cooper was kiddie-stuff; here was the true horror rock. Who the hell were these British maniacs? They were clearly anything but hippies so that was in their favor. You hid this issue of Creem from your parents, but the next time Dad took you to the bootleg cassette store, you tried to ask the Iranian owner if he had any tapes of the Sex Pistols. Your father overheard and informed you that you wouldn’t be getting any tapes by a band with that kind of name. You soon moved back to the States and forgot about punk for a long time. Looking back now, you knew it was beyond your years and in not pursuing it further you were seeking to preserve your own childlike innocence.

11. “Well, I Need Adventure, yes I do, I need adventure every day…”

If you found a first great passion in music, this was in step with your love for books and the movies. Your early reading and book collecting defined your young life. The first two years in Iran, you continued the early literary trajectory you had embarked on in Texas: AA Milne’s Winnie The Pooh books, Beatrix Potter’s dressed animals, Dr. Seuss, Little Golden Books, Disney fairytale storybooks (eventually graduating to their much darker Brothers Grimm source material), and stories and Psalms from the three different children’s Bibles given to you by family members and teachers. You soon graduated to E.B. White’s Stuart Little, J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, and The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. The years went quickly by and soon your father was providing you with wonderful hardbound editions of The Call of the Wild by Jack London, Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, all of which remain among your favorite American literary works. You also enjoyed the pulpy western novels of Zane Grey, Elmore Leonard, Louis L’Amour, and Tarzan author Edgar Rice Burroughs. You amassed a sizable child’s library as the years in Iran flashed by. Your book collection came from several sources; some were presents sent from the states or picked up there on visits home, but most came from the wonderful bookstores at the Tehran American Society and the Pars American Club as well as a neighborhood market that had a newsstand with a small selection of English language titles. As always, most of the books offered at these shops were British rather than American.

You soon grew into the American comics craze, religiously following the exploits of Superman, Batman, Captain America, Captain Marvel (you liked the DC iteration better than Marvel’s), The Phantom, Tarzan (of course), John Carter of Mars, Master of Kung Fu Shang-Chi, The Karate Kid, Doctors Strange and Savage, Moebius the Vampire, Werewolf by Night, Will Eisner’s nostalgic and noirish The Spirit (a big favorite for years), the gloomy and violent WWII saga of Sgt. Rock, the weird old west of Jonah Hex, and anything featuring the work of Jack Kirby who, along with Frank Frazetta, was among the first artists you came to know by name. In addition to the superheroes and adventurers of the DC and Marvel universes, there was also a brand called Classics Illustrated, which as the name suggests artfully interpreted great works of world literature into palatable comic book form for children, providing your first exposure to many lauded tales you would later read and love. But the pulpy and underappreciated Marvel Comics went a long way toward your education and inspired a fascination with history.

The Marvel universe was not only way darker and far more “grown-up” than DC, but Stan Lee and Jack Kirby also provided many jumping-off points for future literary and historical obsessions. For example, you can vividly recall some of the masterly panels of a particular Avengers storyline wherein the gorgeous Scarlet Witch finds herself transported back in time to the Salem Witch Trials, where she is persecuted by none other than the real-life villainous puritan preacher Cotton Mather. This was the real old, weird America and the story was exceedingly sinister and full of menace. When you actually read some of Mather’s sermons and the works of Nathaniel Hawthorne years later, it was those long-ago read Marvel Comics that provided some context.

Batman was the only DC hero who came close to the sinister malevolence of the Marvel world; established characters like Robin were even killed off as the 1970s progressed. And of course, The Joker was the greatest comic book villain of all time. But Marvel’s Spiderman was inarguably your favorite superhero for most of your comic-reading years. Unlike the fictional cities of Gotham and Metropolis inhabited by the DC brand’s caped crusaders, Spidey was slinging his web in a very real and dangerous contemporary New York City. The Spiderman rags were even more hardboiled than the urban noir of Batman; by the early 1970s the stories were full of heroin overdoses, LSD trips, and the violent street life of New York, which at that time was seemingly on its last legs and much more of a third world city than the Tehran you inhabited. Through Spiderman, you became obsessed with the dangerous milieu of gritty 1970s Manhattan, and the comics would inadvertently create a bridge to future loves and fascinations, to Saturday Night Fever, the early CBGB punk scene, the music of Lou Reed, the underground orbit of Warhol’s Factory, the films of Martin Scorsese and Abel Ferrara, hardboiled detective fiction and the Beat writers, and on and on. You harbored tween dreams of moving to a New York borough and perhaps forming your own street gang when you were older and tough enough.

A sort of black market of comic book selling and trading was rampant at TAS. Some comics were highly sought after and rare collectibles, like the various horror anthology series put out by the EC brand, which went under before you were born. Your brother was especially skilled in these underground auctions and often surprised you with a rare issue of one of your favorites.

Like any funny book aficionado, you also carefully crafted your own comics. You helmed a number of series over the years, but the longest running was a secret agent affair whose hero went by the highly unoriginal name of Peter Johnson. In a bid for originality, Johnson’s Oscar Goldman-like supervisor was given the unlikely moniker of Dag Willows. Peter Johnson was an undercover CIA agent who had infiltrated the druggy cults of the hippy counterculture, so he had long hair and a beard, sported dark sunglasses, wore knee-high fringed moccasin boots, and rode a chopper. He also had a beautiful blonde love interest whose name is now lost to time.

Both you and your brother were devotees of the magazine Famous Monsters of Filmland, which provided a monthly course in the classical phase of the history of the horror genre, with wonderful articles on old films you assumed you would never have a chance to see. Between the US and England, there were also several magazines and comic books devoted exclusively to the British horror films of Hammer Studios and these were snatched up whenever they appeared. While you were allowed to read such fare, you were only rarely allowed to see the bloody, bare breasted Hammer films of the 60s and 70s with Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee when they played; your mother felt they were a bit too satanic. Films were very heavily policed by your parents until well into your teenage years, but more on that later.

Like so much of your young life, perhaps beginning with Pooh and Peter Pan, your reading material was often of a decidedly British nature, as books and publications from England were often much more readily available in Iran than those from the States. One of the delights of the young bibliophile in Iran was the gift of the so-called Annuals. These were large and beautiful lavishly illustrated children’s books from England that contained several themed stories mostly focused on the British literary heritage in a “Continuing Adventures of…” type format. Your library of annuals included editions devoted to Peter Pan, King Arthur, Robin Hood, and an omnibus collection of boys’ own adventure stories. Also from the shores of Albion came the English translations of a series of remarkable French books featuring a young globetrotting adventurer named Tintin and his associates. Each volume was presented in a comic book format, but these were thick, properly bound tomes on high quality paper with astonishing popping color. Such works would later come to be called graphic novels. While intended for school-age children, the stories were often very “adult;” for example, Tintin’s best friend was a crusty old alcoholic sea captain and in one book they broke up an opium ring together. The books also taught young readers a great deal about other cultures, as wherever Tintin’s travels took him, the local flavor was presented in vivid detail. They were extraordinary books to read as a curious and well-traveled boy.

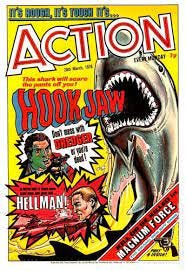

Even more mature and infinitely seedier was Action Comics from England, a monthly loose-leaf periodical which was folded like a daily newspaper and indeed presented in a newsprint format that left your fingers grubby with ink. This was an anthology comic featuring a collection of stories that continued from month to month in the old British boys’ own adventure tradition. Two of the ongoing stories were favorites. The first was “Hookjaw”, which exploited the success of the recent film Jaws and featured a crew of adventurers hunting a mammoth and extremely vicious great white shark. The leviathan had acquired its name due to the harpoon that had pierced its lower jaw and whose protruding hook remained lodged there, rendering the sea beast even more deadly. Amid an ultimate final battle with the sailors, this hook ripped open the stomach of the main hero at the end of one run; imagine the reader’s surprise to find he was stitched up and alive when the next series began after a few months. Action also featured a regular strip decidedly different in tone. “Look out for Lefty” concerned a young professional soccer player getting into evermore hilarious predicaments with each installment, many featuring his eccentric old granddad “Gramps” who added greatly to the side-splitting shenanigans.

There was also a series of thick mass-market-sized paperback books devoted to a John Carter-like fantasy character named Garth, which were collected from comic strips that originally appeared in an English newspaper. In black and white and derivative and unexceptional in many ways, what made Garth stand out was his incessant romantic encounters with beautiful and extremely well-formed women. While the sex wasn’t graphic, it also left nothing to a boy’s imagination and featured lots of lovemaking and partial nudity. You were very aroused by these books and began to add some of their story points to your own playacting scenarios. One day, you were in your bedroom alone portraying Garth in some time traveling adventure and decided a romance scene was needed in the script. You stripped down and were rolling around in bed when you heard your brother come in. You froze and tried to keep the sheets pinned down around you as he pulled at them and taunted you. “Whatchadoin’? What’s goin’ on?” Although he had not yet revealed you, he had figured you out exactly. “Aw you Gawth?” he asked in that absurd Pippa Man baby voice. Finally, he succeeded in pulling the sheet away enough to expose one of your nude buttocks. He ran out of the room, laughing and yelling, “Mom, Flip’s naked!” It was quite humiliating and brought back memories of an earlier incident when you were portraying Tarzan as a young child. Your mother began to have a closer look at some of the horror, science fiction and fantasy books you were reading following this humiliating Garth incident.

12. “What We Do is Secret...”

Both Action and Garth were the British counterparts of an emerging strand of suspicious and seedy American comics that were presumably aimed at more mature boys and were presented in magazine scale, lending them an additional air of forbidden porn-like, under-the-counter contraband. Many of these publications were put out by a company called Warren, the publisher of your cherished Famous Monsters, and included EC-inspired anthology titles like Creepy and Eerie, as well as the impossibly sexy Vampirella, every boy’s succubus dream. Although the comics inside were in seedy black and white, the cover art of these rags often featured stunning full color masterpieces by the brilliant Frank Frazetta, whose work you had come to admire on the covers of Tarzan and Conan paperback novels. While the Warren brand also revised Will Eisner’s classic noir crime fighter The Spirit (another personal favorite followed through the years), the stories within the other magazines were rife with extreme graphic violence, voluptuous nudity, and titillating sexual scenarios. Heavy Metal magazine also debuted during this period, the legendary adult sci-fi and fantasy comic magazine that was beautiful, glossy, strange, otherworldly, mind-blowing, immensely disturbing to a young mind, and at times downright pornographic. One day at the newsstand, you were looking through the new issue quickly to see if your mother would allow you to buy it. In one story, a tiny fairy girl was brutally sexually assaulted by some grotesque giant; you can never forget the frame, drawn and colored in vivid loving detail, of the depraved beast approaching her brandishing his enormous erect penis, followed by explicit depictions of the act itself. While your mother sometimes allowed you to read Heavy Metal, you felt this particular issue would not pass muster and quickly put it back. You felt scarred in some way.

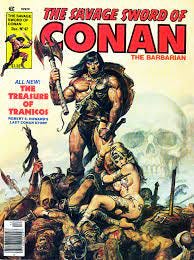

There were also a number of Marvel comic magazines that appeared which were similarly aimed at a more mature readership. This was a way for Marvel to broaden its audience, as magazine-style publications were not required to receive the small white Comics Code Seal of Approval and were therefore able to present copious amounts of sex and violence like Heavy Metal and the Warren titles. The Marvel magazines included titles like The Tomb of Dracula, The Deadly Hands of Kung Fu, Doc Savage, Planet of the Apes, Vampire Tales, and The Savage Sword of Conan. All such publications became increasingly monitored by your mother. She would frequently either tear out the pages featuring offensive material or take certain issues away altogether. Your brother was a fanatical devotee of all things Conan, collecting the entire series of Robert E. Howard novels and Marvel comics, but the sex and violence of the large format Savage Sword of Conan mag was deemed a bit much by Mother, so she would routinely raid his stash and excise the offending pages. While you took such censorship as a matter of course, Louis was outraged and deeply hurt by it, telling you, “How would you feel if there was a Savage Web of Spidey mag and she ripped some pages out of that?” Point taken. For Louis this obstruction of his autonomy and right to self-determination was a wound that seemed to never heal; he would grow increasingly rebellious and resentful toward your parents as the years rolled on.

While overtly salacious and Satanic musical acts like Bowie, Coop and The Stones were not considered corrupting influences by your parents, your reading and film viewing was strictly policed and would remain so for many years. To be fair, the culture shock your relatively conservative parents must have been experiencing throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s must have been intense and disturbing. In just a few short years, popular culture had seemed to have gone over to the dark side. The MPAA ratings system had only been established the year after you were born, allowing mainstream films to be rated R and X and loaded with extreme graphic violence, horrible profanity, copious amounts of nudity, and near pornographic sexual content. Almost overnight, films had gone from being mostly family-friendly to extreme vulgar expressions of some new amorality. Sure, there had always been “adult films” and “adult magazines”, but these existed in a subterranean realm and had to be actively sought out by hypersexed beatniks and hippies and lonely middle-aged men in raincoats. Now, in just a few short years, such seediness had forever soiled mainstream popular culture. Even comic books, strictly kiddie fare, had become infected, although there was no R or X-rating to warn parents of the content. To people like your parents, who were little more than kids themselves at the time, it seemed one of the only victories of the New Liberalism and Hippy idealism was the transformation of pop culture into a dark satanic brew of hedonistic sex, mind altering drugs, filthy language, and sickening violence. To a certain extent, you agreed with them and still do.

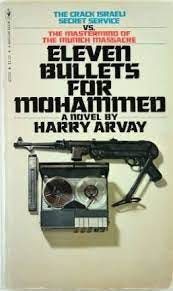

You soon learned that not all books were the holy objects you once considered them to be; some were infernal. You remember an early fascination with your father’s reading material in Iran. He was strictly a Newsweek man, as Time was considered too liberal. Judging by the covers of his magazines, the world seemed to be one huge war zone; images from Africa, South America, Israel, Lebanon, Germany, London, Belfast all united by an iconography of instability, guns, bombs, fires, riots, bloodshed and chaos. One particular Newsweek cover image is forever seared in your mind, two masked men with automatic weapons walking through a field below a single word: “Beirut!” as if the image fully conveyed everything you needed to know about the place. Your father was also a big reader of espionage fiction, in particular John LeCarre and Robert Ludlum. Just reading the back-cover blurbs of these novels conveyed the existence of the shadowy secret world and also suggested to you the idea that Daddy was a spook himself. As you matured in Iran, your reading sometimes took you into the real and violent world of the troubled Middle East you lived in. A very sweet and extremely intelligent friend of yours named Christopher Williams was Jewish and would later work for NASA. Chris turned you on to a series of very grownup paperback novels by a mostly forgotten author named Harry Arvay, published in London by Corgi Books. The protagonist of novels like The Swiss Deal, Togo Commando, and Blow the Four Winds was Max Roth, head of the Israeli Security Branch, who waged constant war against the incessant threat of Arab terrorism around the globe. While your brother preferred the pulpy hitman bloodshed of the Mack Bolan Executioner series, you came to understand something of the actual nearby burning world you had been protected from through Arvay’s works of rather unabashed Zionist propaganda.

Despite her paranoia about Satanism and her aversion to scary movies, your mother seemed to rather enjoy cinematic supernatural horror novels, reading Carrie and Salem’s Lot by Stephen King, Rosemary’s Baby by Ira Levin, and William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist, the latter of which sported a terrifying cover image of a demonic face that gave you night terrors. One day, she discovered you staring at it intently and she asked you to promise her that you would never read that book or try to see the movie. Never? you thought.

13. “I’m gonna smash my Telecaster through the television screen, ‘cause I don’t like what’s going down…”

Moving Images, whether seen or unseen, defined your boyhood. The Brits seemed to have had a monopoly over much of the television programming which aired on the so-called American station and this, along with the similar trend in the availability of films and literature, gave you a sense of growing up English rather than American. The BBC news aired nightly, while you devoured rather literary and intelligent fantasy and adventure shows like Arthur and the Britons, Doctor Who, Last of the Mohicans, and Quatermass. There were also these extremely bizarre and disturbing one-hour BBC TV films for kids, produced by a shadowy body known as The Children’s Film Foundation. These raw gems were generally of a comedic sci-fi and supernatural horror persuasion. Not only did many of these programs draw on ideas related to UFOs, haunted landscapes, and England’s occult history and wyrd past of pagan rites and witchery, they were also full of not-so-subtle left wing political commentary (usually delivered by the tiniest smartass of some overly curious ragamuffin squad). Of course, this was 1970s liberalism, so a climactic (and rather brutal and realistic) fistfight with a bully was a highlight of many shows and was considered an act of heroism to be cheered on by the good kids. But it was these television films’ out and out strangeness that made them so utterly remarkable. Likely created by a team of stoned and subversively inspired hippies just out of art school, they were full of phallic objects made to do funny things as well as intentional sexual innuendoes so blatant that even most kids could catch them, or at least feel something wasn’t right. Strangers from outer space in human form would be invited into small a private room or perhaps a barn by the group of small children, and when Dad discovered them he wasn’t upset in the least by the presence of the weird young man who was suddenly hanging out with his small children without supervision. He also had a long, writhing penile-like appendage poking out of the top of his ‘ead that did zany stuff. Because of these shows as well as much of your reading material, music listening and film viewing, the England of your imagination was a strange and misty haunted landscape rife with supernatural phenomena and endless mystique. But you also enjoyed the snide zaniness of decidedly English comedy shows like Monty Python’s Flying Circus and Man About the House, the latter of which was remade as Three’s Company back in the States.

Noirish1970s cop shows from the States drifted over to Iran and onto the American station after a season or two; cynical and hard-bitten programs that suggested to you that urban America had become a dirty, frightening, and violent place. Another show that made it over was Space: 1999 with Martin Landau, which felt like the pessimistic apocalyptic weariness of too many 70s cop shows had finally worn down the interstellar romance and luster of Star Trek. When you returned home to Texas for visits, you were relieved to find that Fort Worth had not descended into an Alphabet City of junkies and whores or a Sunset Strip of thrill-killing hippies as you caught up on your favorite shows depicting the fall of America from the comfort of your grandparents’ still-intact living room. You loved these shows but they also made you uneasy, as if the world you had come from no longer existed. This feeling was particularly acute back in Iran. The world was on fire. Terrorism and societal upheaval were the order of the day in the early 70s but rarely spoken of directly. The American and BBC nightly news broadcasts portrayed a burning world at the mercy of the Bader Meinhof Group, the Weather Underground, the Black Panther Party, Carlos the Jackal, the PLO, the SLA, the Jewish Defense League, The Red Army Brigade and the IRA. The events in Northern Ireland were particularly curious to you. The social unrest and political violence on the TV screen was generally quite foreign to you; it featured mostly brown and black people from Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa, while the events in Europe were also decidedly foreign due to the language barrier. But in this place called Ireland, the people looked like Brits and spoke a strange, almost indecipherable form of English. Who were these strange white people throwing Molotov cocktails at one another and burning their neighborhoods down? Where was this strange place Ireland? It certainly didn’t look like the same enchanted place as Darby O’Gill and the Little People took place. You asked your dad about this and he replied, “They’re us, son. We came from there a long time ago. Dan Cronin is from there and lived there most of his life.” Dan Cronin hailed from the farmlands near Ballymena in Northern Ireland. He was one of your father’s closest friends in Iran, a very quiet, dashing and handsome Irishman with blue eyes and a red beard. Cronin was quite the man to you boys, a sort of romantic figure, but you had always assumed his gentle and sophisticated brogue was an English accent and it certainly in no way resembled the harsh and guttural pirate-like talk of the Northern Irish of Belfast interviewed on the BBC.

14. “Sailors fighting in the dance hall/ Oh man, look at those cavemen go/ It's the freakiest show/ Take a look at the lawman/ Beating up the wrong guy/ Oh man, wonder if he'll ever know/He's in the bestselling show/ Is there life on Mars?”

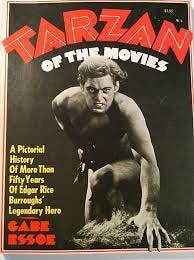

Your reading was often directly tied to your passion for the movies. This went all the way back to your earliest memories, which are of Tarzan no less. You followed his onscreen evolution like a religious devotion, from Weissmuller to Lex Barker to Buster Crabbe to Ron Ely and all Lord Greystokes in between. You loved the Lord of the Apes so much, particularly the Johnny Weissmuller iteration, that you seemed to become him for several years (in fact, your great grandmother called you nothing but “Tarzan” until she passed away during your teenage years, while your earliest documented postcard home from Iran informed your aunt in almost indecipherable six-year old scrawl that “We went to see Tarzan. It was good.”). What better life could there be than to live in a treehouse with a beautiful woman, a “Boy” and a chimpanzee, and to spend your days fighting animals, savages, and white poachers in an African jungle? And if Tarzan movies couldn’t be on TV all the time, well, you would just have to make your own. One of the first handcrafted gifts you remember receiving was a leopard skin loincloth made by your grandmother. You lived in the thing for two years, running around the African bush and ferociously fighting crocodiles, rhinos, and lions; occasionally donning one of your mother’s long wigs for a more feral portrait of the jungle lord. As you began to read, you discovered that there was not one, but quite a few different series of Tarzan comics (the character was in the public domain by that time), and while the DC comics were the best, you collected them all, reading and rereading them. In a lot of these comic book versions, Tarzan was often portrayed as naked when a small boy. Wanting to be faithful to this narrative strand and also inspired by a recent screening of Francois Truffaut’s The Wild Child, you interrupted your solitary playing one day to ask your mother if you could play in your room naked for a while as this was the part when Tarzan was a boy. Mom looked at you with a serious expression, then shook her head. “No. I don’t think that’s a good idea.” You explained again that it was just how he was when he was little. She though it over a bit more and chose her words carefully. “Just play grownup Tarzan for now.” Your devotion to your hero soon came to include the series of original Edgar Rice Burroughs pulp novels as well as forays into the novels and comics of the Tarzan creator’s other characters like John Carter of Mars. One of your prized possessions was a huge encyclopedic tome called Tarzan of the Movies, which explored the complete history of your cinematic hero and acted as your first film studies course.

Your passion for Tarzan was eventually shared with Peter Pan before finally slipping to second place due to your obsession with all things kung fu and Kung Fu. The groundbreaking series featuring David Carradine came on the air out of nowhere when you were a five-year-old boy still in Texas. You watched every episode when it aired and were amazed by its complexity: an Asian karate guy in an old west cowboy setting, the nonlinear flashbacks to his boyhood in China, the Eastern floating world mysticism and slightly hippy psychedelic vibe. Then suddenly, you were whisked away to the otherworldly East yourself and torn away from Kung Fu. Perhaps in an effort to get you to shut up about Kwai Chang-Caine and Master Po, your parents sought out some therapeutic replacements. One was a British hardback Kung Fu annual, which featured stories from the series, interviews with the creators, and even some full color comic strips. Another was the paperback novelization of the series pilot, to you a proper grownup book. Like the show itself, you found the book to be endlessly fascinating, not least due to the artful flashback-driven narration.

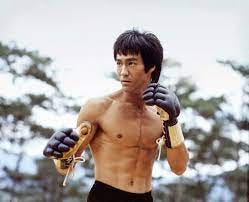

Around the same time, Bruce Lee exploded into popular culture in a big way. Enter the Dragon played and stayed in Tehran for a few years straight, and your father took you and Louis to see it several times. You had never seen an action film like it, or an athlete like Lee. His martial artistry made Carradine seem like a tired old man. Your brother Louis immediately crafted a highly coveted set of nunchakus and taught himself elaborate routines (was there nothing the boy could not do?). Way of the Dragon followed quickly on Enter’s kicking heels, and offered an even better ultimate cinematic showdown than the previous film with an upstart American master named Chuck Norris. At the same moment, a show called Longstreet was being rerun on Tehran’s American station which featured James Franciscus (of Beneath the Planet of the Apes, you noted) as a blind insurance investigator, and the Little Dragon himself would show up there occasionally as a recurring character. Lee’s masterpiece Fist of Fury was soon rereleased and then…Bruce Lee was gone. But he remained everywhere. His final film Game of Death was completed and released posthumously, with Lee and a stand-in battling Kareem-Abdul Jabaar. Episodes from a superhero TV show that aired a year before you were born were compiled and released as a feature called The Green Hornet, with Lee as Kato, a series regular who essentially acted as Robin to the Hornet’s Batman. The world could not get enough of Bruce Lee and neither could you. There were a number of monthly magazines devoted to him, many of which folded out into full-color posters, which you tacked to your bedroom wall. And any martial arts movie magazine of the time was almost singularly devoted to all things Lee, while creating space for David Carradine, Sonny Chiba, Tom Laughlin, the Shaw Brothers, Bob Wall, and Chuck Norris as well. The same was true of the adult Marvel comic mag The Deadly Hands of Kung Fu. While you were still trying to get your head around Lee’s death, your father surprised you with another very grownup paperback, a biography by the Dragon’s widow entitled Bruce Lee: The Man Only I Knew. It was a thrilling read and also featured a flipbook component in the bottom corner of the pages which provided a mini-movie of Lee throwing wild kicks. Does anyone as famous as Bruce Lee ever truly die?

The comics and books you read also allowed you to feed an unrequited lust for films you had not had an opportunity to see. Oftentimes, such reading material was so superior to the films themselves that the movies, when finally seen, proved rather anticlimactic and disappointing. Logan’s Run was one such example. You had read both the source novel (which featured at least one rather strange sex scene with talk of orgasms as being painful and even as “damnation,” none of which you understood) and the entire run of the Marvel Comics series and you were extremely fascinated with the whole world they created, particularly the subterranean tribe of cutthroat young Cubs. When you finally saw the film, you were almost heartbroken. The sets and costumes looked so fake compared to the rich futuristic grittiness of the book and comics that it didn’t even seem like the same universe. Michael York was a skinny somewhat effeminate bloke who seemed woefully miscast as the bad ass Sandman turned Runner Logan (although he was perfect as D’Artagnan alongside Oliver Reed’s burly Athos in The Three Musketeers). Nothing about the film remotely approached the heights that the reading material had taken you to. Although Jenny Agutter made quite an impression on you as always and Farrah Fawcett also made an appearance.

The same was more or less true of Star Wars. You were the ultimate Star Wars geek for over a year before you finally saw the film on a visit home to Texas. As with Logan’s Run, you had read both the novelization and the full run of Marvel Comics but also had collected magazines, picture books, posters, soundtrack cassette tapes, toys, you name it. The book and comics rendered the characters and narrative very grown up to you; something like ancient mythology or Shakespeare even. Fueled by all the ephemera of a film you had never seen, Star Wars the movie could never live up to the Star Wars of your reader’s imagination. It seemed too much like a children’s film compared to the mature drama conveyed by the comics and novelization. It was as though you had been promised one thing and given another. Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated? Perhaps comics and novels are simply better suited for such fare. With the Planet of the Apes comics, however, you had the good fortune to have come to the movies first, so the comics only added to the rich and imaginative experience you enjoyed in that post-apocalyptic cinematic realm. The original Planet of the Apes film cycle rolled out steadily and defined your years in Iran. The original had come out when you were but a baby in Texas, but it was brought back to Iran every time a new sequel was on the way.

Mad Magazine was a highly subversive publication that was aimed at extremely smart and extremely smartass kids, engaging in an endless anarchic skewering and satirizing of pop culture. It was a consistent form of education while you were overseas and a guidebook to what was going on in America, including all the great movies and TV shows you might never see. Through the scathing movie send-up comic strips of Mad (and later a knock-off called Cracked), you became aware of the so-called New Hollywood of the 70s and learned about hardboiled New York adult films like Network, Dog Day Afternoon, and The Godfather and you looked forward to the day you might see them. Film in the 70s was forever cloaked in mystery, a forbidden fruit you could only dream of devouring someday. Movies became holy relics you often had to wait years to see while in a constant state of fevered anticipation.

15. “Fighting old King Kong, I can be any hero at all; Zorro or Don Juan, I know I’m the King of the Silver Screen…”

Among your prized possessions in Iran was the collection of huge color posters put out by a British company called Pace which your father was able to get for you somewhere in town. Each poster was a high res blowup of a still photograph, popping with grainy vibrant color and so large that each one took up the better part of a wall. You had one of Bruce Lee, one of Alice Cooper, another of an early 1970s Elvis Presley looking like a coked up professional wrestler, and not one but two posters of Easy Rider, a film you had not seen but whose iconography hypnotized you. Both posters featured stars Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper heading down the highway looking for adventure on their beautiful choppers, while one also included Jack Nicholson on the back of Fonda’s American flag machine. Fonda and Hopper watched over you at night, like the ghosts of America itself. You found Fonda, with his wraparound shades and skintight blue leathers that matched his bike, to be the most compelling at the time and since you assumed your dad had seen the film, you asked which guy he liked the best. “Probably Hopper,” he said. “Really? He looks like a mean, scary hippy!” you ignorantly retorted. Perhaps a year after this exchange, Dennis Hopper himself stumbled into Iran for a brief moment at the height of his battle with alcohol and cocaine. He claimed to be researching his next film. Rather coincidentally, a friend of your father’s at the State Department was assigned as part of the chronically stoned actor’s security detail and your father was invited to tag along with them one day. Hopper was at his most obnoxious during the visit, totally drunk by midmorning, jabbering nonstop, and likely the last person you would want to have to shuffle around a Muslim country whose peasants already hated Americans. The day your father was along for the ride, Hopper insisted on going to a sprawling auto graveyard outside of Tehran. He claimed he wanted to buy the land and build a cowboy boot factory using the Iranians’ renowned leather working skills and their exploitable cheap labor. “Or maybe just build some condos, man. Heh heh heh. Ya dig?” Once on site, he quickly forgot the purpose of the mission and instead began shooting up the junkyard with the various firearms he begged off the two Iranian soldiers who were part of the entourage. Apparently, he slipped out of the country the next day without anyone’s knowledge, presumably to Beirut or some other nearby destination where narcotics were easier to find and cheaper. Sometime after this, knowing he would not remember you asking previously, you pointed to one of your Easy Rider posters and asked Dad again, “Which guy do you like the best.” Without missing a beat, he replied, “Nicholson.” You would not see Easy Rider until years later on late night network television safely back stateside, and after all the buildup in your mind it was initially a bit disappointing, failing to live up to the movie of your imagination. But you were faithful in these matters and it ultimately became a personal favorite. As for Hopper, he, along with Fonda and Nicholson, would eventually become one of your most treasured actors.

There were three movie theaters that showed English language films in Tehran, but only the prestigious Ice Palace’s name remains in your memory, so called because the cinema was a fancy affair housed over an ice rink and you could look down on the skaters through a wall-spanning window in the red velvet-draped lobby. The Ice Palace was a repertory house that mostly played classic family-friendly films. Early on, your mom told you they were taking you to a surprise movie, which turned out to be a feature film version of your favorite American kid’s show H.R. Pufnstuff (you even had your own Freddie the Flute which Mom had ordered from the back of a box of Fruit Loops back in Texas). There was a steady supply of animated Walt Disney fairytale films; your favorites included Fantasia (a serious art film), Pinocchio (the best of them all; a work that will never lose its spellbinding sense of wonder) Sleeping Beauty, Snow White (both the scariest of the old Disney animated features) and of course Robin Hood and Peter Pan. Beginning with those characters, you never ceased to love the pulpy old adventure classics, so anything featuring highflying adventure at theater was made to order. If a film had knights in shining armor, pirates, Vikings, Musketeers, or any kind of swordplay and swashbuckling action, you were quite content as a child. In addition to the epic Arthurian musical Camelot with Richard Harris and Vanessa Redgrave, three such films deeply impressed you at the Ice Palace. The first was Michael Powell’s 1940 Technicolor version of The Thief of Bagdad (you also dug the 1961 Spaghetti version with Steve Reeves), and the other two were a pair of companion swashbucklers starring the brilliant Burt Lancaster. While The Flame and the Arrow (1950) and The Crimson Pirate (1952) were helmed by different directors, both films were vanity projects for producer Lancaster, who wanted to show off his legendary circus acrobat training and swashbuckling skills. The films also allowed him to move from the urban hells and dusty plains of America to the high seas, lush forests and medieval castles of olde European lore, and to present a more dashing, lighthearted comedic side that was miles away from the hardboiled noir and cowboy persona that had made him a star. Both films also featured the Hollywood icon’s real-life sidekick, physical trainer, and former circus act partner Nick Cravat. Cravat appeared to be a deaf mute, which lent a Chaplin and Keaton style quality to his highflying hijinks. While derivative of any number of Robin Hood films and high seas swashbucklers, these were wonderful kids’ fare and made you a lifelong fan of Lancaster.

You never tired of yearly screenings of the genre-defying MGM classic The Wizard of Oz (especially those flying monkeys!) or Stanley Kramer’s madcap epic comedy It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World at the Ice Palace. You were enchanted by The Sound of Music and Jerry Lewis’ hilarious antics in The Nutty Professor also made quite an impression (at the time you never imagined that you would one day be one yourself). There were multiple screenings of Fiddler on the Roof and Seven Brides for Seven Brothers. There were also screenings of films that were quite questionably rated G, such as One Million Years BC with the ravishing scantily clad cave girl Raquel Welch. And there was Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. As for the latter, it deeply disturbed and haunted you and you could not fathom how such a strange and horrific drug-trippy film had received a G rating. It was psychedelic light years away from Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon and you felt blessed to have seen such a complex and ineffable adult spectacle even though it left you with 2001 questions. Around this time, Marvel put out a comic book series based on the film and you read them all, hoping for some insight into the monolith, the Starchild, and what the hell exactly happened to Kier Dullea; however the comics were as grownup and impenetrable as the film and you were left with the same sense of wonder and mystery.

As with the availability of boys’ literature in Tehran, the Ice Palace cinema was generally biased toward more British-flavored fare, but all the better! Many such films that showed at the theater also became yearly pilgrimages. Willie Wonka & The Chocolate Factory with Gene Wilder was one and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang with Dick Van Dyke was another. How Mother and Father continued to sit through such rather overlong children’s fantasy films time and time again is a testament to their parenting legacy. During one screening of Chitty, the theater was full of rowdy Iranian kids who booed loudly throughout the first reel of the film; you were not sure why at first. Finally, the projectionist somehow changed the soundtrack over to the Farsi language version and the belligerent crowd burst out in wild applause and cheers. Disgusted, your father dragged the family out of the theater; he had, after all, paid for his kids to see the film in English. Another yearly screening at the Ice Palace was Scrooge with Albert Finney during the Christmas season. It became one of your favorite films upon the first viewing; such wonderful songs throughout and the supernatural horror movie aspect thrilled and terrified you. No amount of critical arguing would ever convince you that this was not the ultimate adaptation of the Charles Dickens classic. No other version even holds a midnight candle to it; so wonderful year after year and, to this day, Scrooge remains Christmas to you and Finney’s performance grows more astonishing with each yearly viewing.

Another oft-repeated Dickensian viewing at the Ice Palace was Sir Carol Reed’s Oliver! No amount of screenings seemed to make this film grow old to you; there was always something new to discover. You couldn’t get enough of Rod Moody’s hilarious and charming Fagin or Pufnstuf star Jack Wild’s streetwise urchin the Artful Dodger. And it was here you discovered your first fascination with an actual actor rather than with a character in a movie; an infatuation with the player rather than the part played. The actor was Oliver Reed who played Bill Sykes, but who was doing infinitely more than that. Reed had some sort of visceral presence apart from the role he was playing, some life-force beyond the edge of the screen, a damaged strength and entirely masculine beauty and presence that you seized upon and could not explain to yourself. It was as though all the other actors in the film went about their business while Ollie burst forth from the screen and was right before you in person; as if a supernatural transaction had occurred and the liminal barrier between the photographed image on the screen and outer reality had been breached by some dimension-hopping pirate. Your mother felt the same way, asking your dad during the drive back home following the first viewing, “Isn’t that Oliver Reed wonderful?” Ollie became your first in a long line of “favorite actors” who you admired in an almost holy sense; a list that would come to include Argo, Bogart, Brando, Bronson, Burton, Cagney, Caine, Clift, Dafoe, Fessenden, Gould, Hoffman, Hopper, Howard (Trevor, that is), Keitel, Lancaster, Laughton, Oldman, Pacino, McQueen, Nicholson, Oates, Sutherland, Welles. But to put it in sentimental romantic terms, Oliver Reed was your first and remains to this day quite special.

Another of Iran’s English-language cinemas was on the second floor of a kind of shopping mall accessed by escalator; the lobby was an immense white-washed affair that was always decked out with fascinating posters for current features and coming attractions. It was something close to a real American grindhouse and seemed to be devoted to exploitation films and violent and sleazy action cinema. This is where you first enjoyed favorites like Enter the Dragon (multiple times); Paul Bartel’s Death Race 2000 (with David Carradine, Sly Stallone, and Mary Woronov), Brian Trenchard-Smith’s The Man from Hong Kong (with former 007 placeholder George Lazenby), The Odessa File (with Jon Voight), Black Belt Jones (with Jim Kelly), Three the Hard Way (with Kelly, Jim Brown and Fred Williamson), and Rollerball (multiple times), along with countless other hardboiled classics of the 60s and 70s. There were also European cinematic oddities like the German Blaxploitation adaptation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and a strange Italian exploitation version of Jack London’s White Fang starring Sir Lancelot himself, Franco Nero. Along with many strange low-budget espionage thrillers from England (including one in which a somewhat grown-up Mark Lester from Oliver! appeared in a nude scene), here you saw gritty British films like Ransom and The Molly Maguires with Sean Connery and Alfred Hitchcock’s giallo-inspired Frenzy (you loved the trailer as well, with Hitch walking around the grainy streets of 1970s London explaining to the viewer, “Here is the scene of another horrible murder…”). You also saw the new Bond films with Roger Moore as they arrived, which you enjoyed more than the Connery ones. You had a collection of amazing toy cars from the 007 films, including Thunderball’s silver Aston Martin and the Lotus Esprit from The Spy Who Loved Me. These were lovingly crafted by a British toy company called Corgi (perhaps the same company that put out a lot of the paperback books you read) and were not only intricately detailed but also included the films’ iconic gadgetry. In addition to other moving parts, the Aston Martin had an ejector passenger seat that launched the villain into the air, while the Lotus transformed into a submarine with the click of a button. Corgi also put out a Chitty Chitty Bang Bang car with retractable wings and other nifty gadgets.

In addition to Bond, your heroes quickly became the macho and hyperviolent Marlboro men of the 1970s New Hollywood. You idolized Steve McQueen (Bullitt, The Getaway, Junior Bonner), Burt Reynolds (White Lightning, Gator, Deliverance) and the toughest bastard of all, Charles Bronson. You would try and see anything such actors appeared in if allowed. Bronson was badassdom personified in hardboiled flicks like the Elmore Leonard-penned Mr. Majestyk and Walter Hill’s The Street Fighter which co-starred James Coburn, another great and grizzled tough guy. You were deeply disappointed when you were informed you would not be allowed to see Michael Winner’s Death Wish, which seemed to be the ultimate Bronson flick. In an attempt to pacify you, your parents instead took you to see a film called Raid on Entebbe, in which Chuck led a team of Israeli soldiers into Uganda to free hostages taken by the ruthless dictator Idi Amin. As played by the brilliant Yaphet Kotto, Amin put on this very deranged folksy nice-guy act when he spoke to the hostages, smiling and laughing as though he intended them no harm. To any adult viewer this was a chilling portrayal that perfectly captured the unhinged psychosis of the real-life dictator and gave the film an unbearable tension. But you didn’t understand the film at all and asked your parents why Bronson and his team of good guys wanted to kill such a sweet man. Bronson was also among The Magnificent Seven, a team of western gunslingers that included Yul Brynner, James Coburn, Steve McQueen, and Eli Wallach, as well as The Great Escape with Coburn, McQueen, Richard Attenborough, James Garner and Donald Pleasance. Both were regularly programmed at Tehran’s actioner theater. A good time was had by all (heterosexual American males).

The Great Escape spawned a series of testosterone-driven World War II Men-on-a-Mission films which also played regularly. The Dirty Dozen almost eclipsed McQueen’s iconic motorcycle jump in the earlier film with an ensemble cast of tough guys that included Bronson (of course), Jim Brown, Ernest Borgnine, John Cassavetes, Lee Marvin, Ralph Meeker, Robert Ryan, Telly Savalas…You get the picture. There was also Kelly’s Heroes, a gang of misfit soldiers led by Clint Eastwood that included Savalas, Carroll “Archie Bunker” O’Connor, Don Rickles, Donald Sutherland and Harry Dean Stanton among its ranks.

The early to mid ‘70s was the golden age of the antihero-driven revisionist western (or anti-western or hippy western) and you were quite at home on the revisionist range. This new breed of horse opera exploded the American mythology of the John Ford/John Wayne classical phase of the genre with graphic bloody violence, overt sexuality, and an aggressive countercultural and antiauthoritarian sensibility. Among such films you saw at the grindhouse, there were strange spaghetti western knockoffs like Navajo Joe with Burt Reynolds and raunchy old west sex comedies like The Cheyenne Social Club with James Stewart and Henry Fonda, Sam Peckinpah’s The Ballad of Cable Hogue with Jason Robards and Stella Stevens, and From Noon Till Three with Charles Bronson and his gorgeous wife Jill Ireland. You were left shell-shocked by the gory mutilation of the Sioux initiation ritual undergone by Richard Harris in A Man Called Horse as he was suspended in the air by chest piercings. There were also smart genre hybridizations like the sci-fi western Westworld with Yul Brynner riffing on his Magnificent Seven legacy and its sequel Futureworld with Peter Fonda.

You also discovered a great director and were introduced to three lifelong favorite actors through a single exceedingly bizarre western, Arthur Penn’s The Missouri Breaks. Jack Nicholson was everywhere during this period, perhaps the most famous contemporary actor in the world, and his image was even tacked up in your bedroom. He was quite a familiar presence to you by the time you saw the film, however you hadn’t been allowed or hadn’t had the opportunity to see any of the films that had made him a star in the 1970s (Five Easy Pieces, Chinatown, The Last Detail, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, etc.). Nicholson’s sidekick in the film was played by the most naturalistic and prodigious of great character actors, Harry Dean Stanton, while his nemesis was none other than Marlon Brando, who wore a dress and a bonnet in the film and delivered a truly unhinged and menacing portrayal. As with Nicholson, a boy needn’t have ever seen Brando in a film to feel a sense of intimate knowledge of the rebel actor; after all, this was the era of The Godfather and Last Tango in Paris and the media hype around such films was not unlike that surrounding Jack’s films of the time. (The same was true for other actors in Hippy Hollywood; you might not have seen Bonnie and Clyde or Shampoo, but you sure as hell knew who Warren Beatty was). Although The Missouri Breaks is often reviled by critics, it remains one of your favorite westerns of the period and the scene in which Brando wakes up to discover that Nicholson has cut his throat in his sleep remains one of the most powerful and startling moments in the history of the genre. Soon after, you saw an older Arthur Penn film that deeply impressed you with its intensity and contemporary Texas setting, a modern-day western called The Chase which featured Brando, Redford, Angie Dickinson, Robert Duvall, Jane Fonda, James Fox, and Paul Williams among others.