Happy 109th birthday to the late great cinematic magician and genius Orson Welles, one of only a handful of major American film auteurs (along with Altman, Cassavetes, Huston, and Kubrick) to consistently mine the heady terrain of the international art cinema.

Having recently binge-watched the wonderful limited series Ripley on Netflix, I can safely assert that in addition to its faithfulness to the source material of author Patricia Highsmith, the show’s rich and baroque black and white visual design and overall mood is a clear homage to the classic films noir of the 1940s and 50s, a genre some would say Welles, along with faithful cinematographers like Greg Toland, all but invented. [0] Beginning with 1941’s Citizen Kane, Welles would continue to define and reinvent the genre that would come to be known as film noir for over two decades.

I wrote the following piece for a film noir course taught by a jazzy cat named Bob Nagy at the University of North Texas, which was one of the most enjoyable classes I ever took; all we did was watch great old movies and discuss them and read the Philip Marlowe crime novels of Raymond Chandler and other related literature. Bob rather generously approved my proposal to write about the entire first two decades-plus of Welles’ career rather than a single film noir. I later used this term paper as assigned reading in various film courses I taught at Austin Community College. The Welles essay certainly demonstrates undergraduate-level student writing and film analysis but I hope you enjoy it anyway. Thanks as always for reading.

ART OF DARKNESS: ORSON WELLES and FILM NOIR

The late Orson Welles has become somewhat of a folk hero for critics, theorists and filmmakers since his death in 1985. His importance to the history of modern cinema has taken on a mythological scope, positing him as a martyr whose genius was forever undercut by the machinations of the Hollywood industry. His directorial debut Citizen Kane received largely favorable reviews upon its release in 1941, but the film was hardly the financial success RKO had anticipated when they lured Welles to Tinseltown, following his groundbreaking stage and radio careers. He continued to make films both inside and outside of Hollywood, but the new golden boy had let the old men down, and Welles would never again be granted more than a modest budget to direct a feature for a major studio. Today, of course, Kane is considered by many to be the best film of all time, one that broke the boundaries of cinematic expression and continues to influence and inspire contemporary filmmaking on many levels. Welles is revered as a man ahead of his time, unappreciated and ostracized by an old guard blind to the future of the medium.

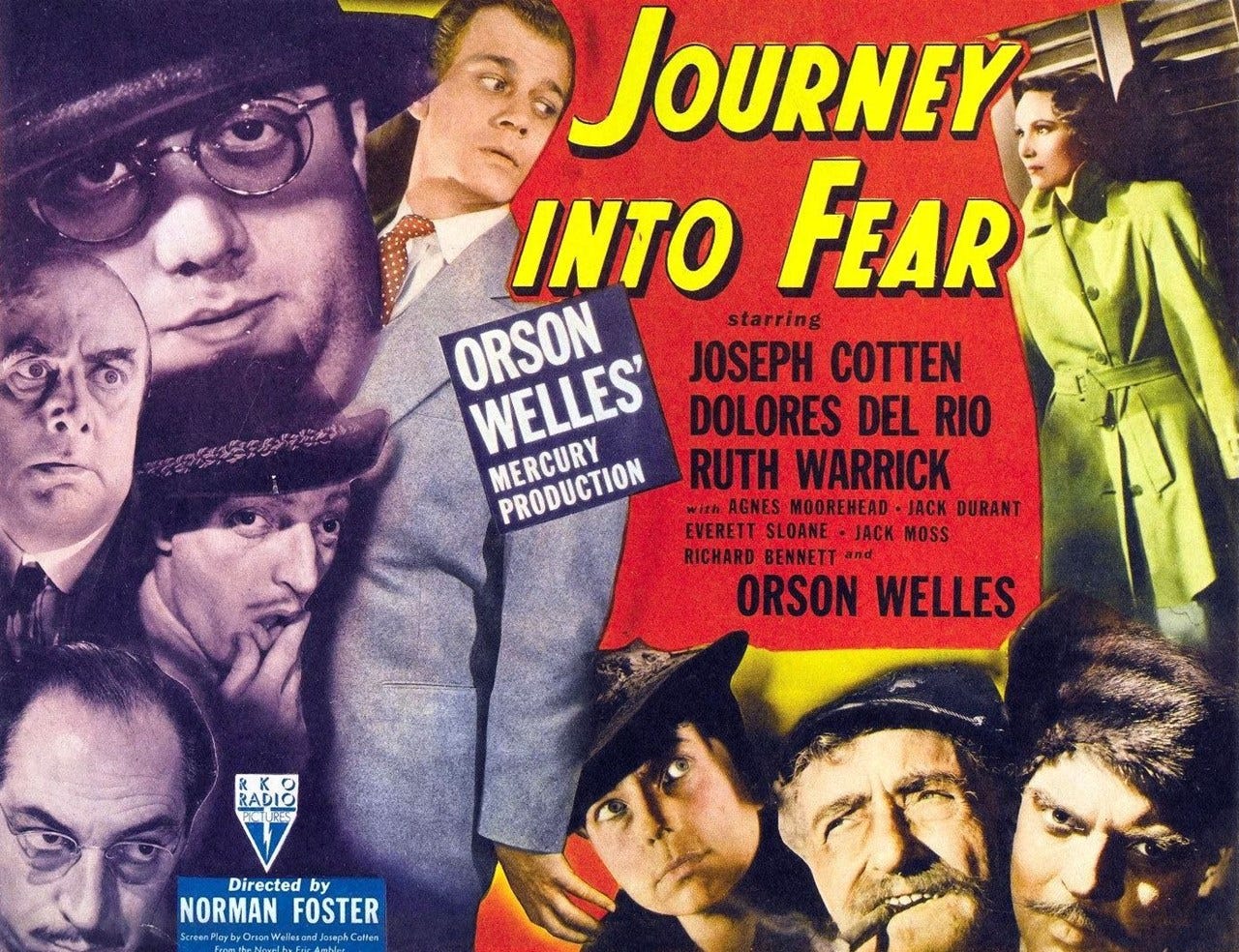

With Citizen Kane, Welles also began his rich contribution to the cinematic movement eventually known as film noir. His 1958 film Touch of Evil is widely considered the last film of the noir cycle, and in the 17 years between, Welles’ imagination remained virtually steadfast to the nightmarish terrain of the “black film”, directing Journey into Fear, The Stranger and The Lady From Shanghai between 1943 and 1948. His noir stylings and sensibilities are also evident in his 1949 collaboration with director Sir Carol Reed, The Third Man; and would continue to inform his later European works like Mr. Arkadin and The Trial.

Critics and theorists continue to debate what it is that comprises a film noir and what the term actually signifies: Is it a genre, a style, a movement or a tonality of film? Is it visual or thematic or both? Is it time-bound and culture-bound within American films of the 1940s and 50s (an argument which discards the cycle of French and British entries as well as acknowledged Euro-American noir classics like Night and the City) or can later films and foreign films be classified as noir? For the purpose of examining Welles’ films, some widely agreed upon aspects of film noir should be delineated.

Film Noir was a term coined by French critics in 1946 to describe the “new mood of cynicism, pessimism, and darkness” of recent Hollywood films.[i] Such films are thought to reflect an unspoken collective anxiety and disillusionment that plagued urban America following the entry into World War II. This has been attributed to a variety of social and economic factors, as well as international tensions. Film noir was also inextricably bound to the contemporaneous “hard-boiled” literary tradition, writers like Ernest Hemingway, Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, James M. Cain, and Cornell Woolrich. The books and films of the movement shared not only disorienting and convoluted narratives (and mostly urban California settings), but also the same nihilistic visions of crime, corruption, violence, eroticism, paranoia, alienation, despair and obsession. In short, a tough existential view of a cruel, treacherous and uncaring world. To convey such depravity and disorientation on screen, directors like Robert Siodmak (The Killers; Criss Cross), Otto Preminger (Laura; Angel Face), John Huston (Asphalt Jungle; Key Largo), Billy Wilder (Double Indemnity; Sunset Boulevard) and Orson Welles worked with faithful cinematographers to create a distinct visual style. Low-key, or chiaroscuro lighting created the “shadow and darkness” of the “mysterious and unknown”.[ii] Bizarre camera angles, deep focus photography and wide angle lenses added an unsettling, off-kilter mood and emphasized the features of grotesque characters and situations out of control.

Much of the “look” of noir is owed to the influence of the German Expressionist movement of the silent era, which utilized many of the same cinematic effects of the later American crime thrillers to create offbeat horror movies like Robert Weine’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1921). Fritz Lang used the same techniques to create noir prototypes like 1931’s M., and Hollywood directors like James Whale and Tod Browning turned to some of the same principles to create the classic Universal horror films of the 1930s. That German expatriates like Siodmak, Preminger, Lang and Wilder would carry the Expressionist torch onward is hardly remarkable, however it was Welles and cinematographer Gregg Toland who seem to have first imported the idea to the Hollywood mainstream with Citizen Kane.

The Expressionistic style as utilized in Kane came ironically enough out of a desire for a new realism in cinema. To accomplish a sharp focus style, Toland experimented with “high powered arc lights, coated lenses, super-speed (XX) film, and low f=stops”[iii], a combination which would become integral to the high contrast look of noir. As Welles scholar Simon Callow has noted, “The finished result seems to us, now, the opposite of real. It seems stylized in the extreme.”[iv] The same is certainly true of the noir films that it inspired, where weird formalistic imagery conveys a very recognizable contemporary America, accompanied by ethereal jazz scores and harsh dialogue laced with colloquial street jargon. Welles’ insistence that a set’s ceiling be in the mise-en-scene was intended to convince the viewer of the reality of the space; this however required Toland to adapt unorthadox low-angle approaches to shooting. The noir films exaggerated such radical camera placements to produce nightmarish visions of a very real modern America. It is worth noting that John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon, also released in 1941, contains little of the rich visual style that would come to characterize both Welles’ work and the noir films, although it is widely agreed that it is the first entry in the cycle.

Citizen Kane’s innovative cinematography accompanies other conventions and techniques that resurface in the later cycle. Welles’ experimental and innovative use of sound and music effects in the film contributed greatly to the soundscapes of the later noir films, with their symphonies of urban noise, musical motifs and interludes. The narrative structure of Kane was virtually robbed for Siodmak’s expanded adaptation of the Hemingway short story “The Killers”, released in 1946. As in Kane, an investigator slowly pieces together the story of the dead protagonist, revealed through various characters in flashback and voice-over. Both films also include visits to a seedy jazz club for information, and a clever “MacGuffin”: The enigma of the word “Rosebud” in Kane, and a mysterious Irish scarf in the Siodmak film. The ambiguous, puzzling, and doomed character of Charles Foster Kane, played by Welles, is clearly an antecedent of the noir anti-hero made famous by the likes of Robert Mitchum, Alan Ladd, and Burt Lancaster in days to come. Joseph Cotten is also featured in the cast, soon to become a noir mainstay, collaborating with Welles on Journey into Fear, The Third Man and Touch of Evil, and, more famously, with Alfred Hitchcock, playing Uncle Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt. Kane’s portrayal of shady politicians would also become a standard in noir films like The Glass Key released the following year.

There is a cynicism to Kane that perhaps accounted in part for its poor reception, a theme of the empty promise of power and wealth, and intimations of a corrupt America that would soon be par for the course in American film. Before turning his attention to scripting Kane with Joseph Manciewicz, Welles was planning to adapt Joseph Conrad’s novella “Heart of Darkness” as his first film for RKO. Conrad’s exploration of the dark side of man has much in common thematically with noir, and surely influenced the fatalistic themes and unorthodox cinematography Welles and Toland pioneered in Citizen Kane.

Following the disappointment of Citizen Kane, Welles was still under contract to RKO. Perhaps seeking to redeem himself in the studio’s eyes, he directed, and did not act in, a conventional period melodrama called The Magnificent Ambersons, which again starred Joseph Cotten and was released the following year. In 1943, RKO released Journey into Fear. The film was scripted by and starred Welles and Cotten and, although credited to Norman Foster, Welles directed much of the film as well. The project went through several hands before Welles seized control, “convinced he could create a more gripping and mysterious film”.[v] Perhaps more an espionage thriller than a true film noir, Welles continued to show a heavy inclination to depict the dark side of human nature and to do so with innovative formalism. The story concerns a young mathematician whose firm sends him to install weaponry on a Turkish warship at the dawn of World War II. He is hunted in Istanbul by some particularly nasty Nazi agents and escapes to Russia on a boat only to find himself in more peril. Cotten portrayed the young protagonist and Welles cast himself as a Turkish special agent. Jack Moss, a professional magician and newest member of Welles’ Mercury troupe, was cast as the Nazi assassin on the condition that he would have no dialogue. Welles agreed to the demand, and Moss’ performance “took on a more evil and ominous character than… if he had been forced to speak”.[vi] The fat, apparently mute Nazi psychopath is typical of the noir fascination with grotesque and repulsive menaces. The film also features a scene in a sleazy cabaret in which a femme fatale attempts to seduce the hero, then his life is spared when his would-be assassins mistakenly shoot the wrong man in the crowd. Packed off to sea by Welles’ Turkish agent, the hero continues to fend off the advances of the sexually aggressive woman, who has also booked passage. Soon, he realizes the Nazis are on board with him, but is unable to convince the crew that he is in danger. Arriving in port after a nerve-wracking journey, he is captured by the killers but manages to escape to the hotel where his wife is staying only to find that the assassins have gotten there first. The climax finds the hero pursued by the Nazis through a window and along the narrow ledge of the hotel’s facade in the pouring rain.

As Frank Brady has documented, the film version of Eric Ambler’s novel of intrigue was cannon fodder for the censors, who attacked the film’s sexuality, portrayals of foreign people, and political message with far more fervor than they would later exercise on the screen adaptations of Chandler and Cain:

…Cotten’s dialogue and certain scenes with Josette would have to leave no doubt that Cotten was not considering adultery. Jose’, an apparently willing cuckold, was too decadent. References to “girlies” and “other places” more interesting than the seedy Le Jockey cabaret were also considered too suggestive. Such changes…were fatal to Welles’ script and the whole theme of Ambler’s novel: Journey plunged Graham, the innocent, into a world where life is cheap and moral standards are conspicuously lacking…every personal habit of the foreign characters, is suggestive of obscenity. Haki reads Krafft-Ebing and correctly describes Banat as a “pervert”. It is this depraved world, as much as the threat of death, that bathes Graham in a perpetual cold sweat. [vii]

As late as 1943, the morally ambiguous aspects of film noir were still being heavily policed. With America about to enter the war as the film was being produced, it was practically impossible to address any issues of race, nationality, or politics, and the finished film was dumbed down to the level of being practically incomprehensible. Thankfully, Welles’ dark visions would be less hampered by studios and censors as time went on. Still, as Ambler notes, “what saves Journey is its ambiance, evoked to a great extent by the low-key lighting effects of (Karl) Struss, and the scenes worked out by Welles (before Foster took over directing).”[viii] In addition to its unusual visual composition, Journey into Fear features many other staples of the noir cycle; most notably the femme fatale; the “water motif”; the attraction/revulsion to the foreign and exotic; duplicity and mistaken identity; and the “grotesque psychopath” archetype, portrayed brilliantly by the silent Moss, with his “reptilian stare from behind thick, steel-rimmed glasses” and “hat pulled down to eye level until he was all double chins”.[ix]

For critics who argue that noir can only be set in the streets of America with the occasional foray into the border towns of Mexico, Journey into Fear cannot qualify as such. Welles’ next film was another Nazi thriller, this time set in “Small Town”, USA. The Stranger was released in 1946 and marked the end of his contract with RKO. Again, Welles directed and starred, sharing uncredited screenwriting duties with John Huston. The film also featured Edward G. Robinson, the gangster movie actor who successfully reinvented himself as a noir icon in films such as Scarlet Street (1945) and Double Indemnity(1948). Welles seemed to be jumping onto the tail of a sub-cycle within the movement, a series of films that portrayed a lurid menace lurking just beneath the tranquil surface of suburban America. Strikingly similar entries include Christmas Holiday (1944), The Suspect, Conflict, and The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry (all 1945). The trend seems to have begun following the success of Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt in 1943. Oddly enough, it is Joe Cotten who portrays the sociopathic Uncle Charlie in Hitchcock’s film, while he is conspicuously absent in Welles’ fourth production, essentially a knock-off of Shadow.

The Stranger is not among Welles’ finest, but in many respects, he continues to define and refine noir aesthetics. It would prove to be his only box office success, and the story by Victor Trivas was nominated for an Academy Award. Welles admitted that he “wanted to do a film to prove to the industry that I could direct a standard Hollywood picture, on time and on budget, just like anyone else”[x] and later disowned the film. Still, it has many of his signature flourishes. The long takes, deep focus cinematography, strange camera angles, and thick, obscuring shadows had become trademarks of the Welles style, and would soon be synonymous with the films of the noir cycle as well. The Stranger begins with a Nazi prisoner’s escape aboard a ship, affirming Welles’ fascination with the sea and further entrenching the motif of water into the world of the cycle. Welles portrays Kindler, a Nazi war criminal masquerading as a professor in a small college town, and Robinson is the special agent on his trail. One chilling scene gives the viewer a film within a film, as Robinson’s agent projects footage of actual Holocaust atrocities to convert the unbelievers. He steps in front of the projector and the second film flickers creepily across his features. The climax finds Welles hiding out in an eerie clock tower with his wife, the daughter of a Supreme Court Justice. He attempts to murder her before being gruesomely impaled on the face of the clock and falling to his death. Robinson’s parting words to the young widow are cruel and cynical: “Pleasant dreams.” Themes stretching back to Kane take on a sharper edge here- Duplicity and deceit, the past haunting the present, and a failed American dream, all of which by this time were becoming part of a general movement in Hollywood cinema. It was also, like Journey into Fear, a “man on the run” tale, a theme Welles would repeatedly return to, as would other directors in films like The Killers (1946), Out of the Past (1947), and Asphalt Jungle (1950).

His next film proved Welles was at the top of his game within the new movement. He wrote, directed, and starred in The Lady from Shanghai, released by Paramount in 1948. The female lead was Rita Hayworth, Welles’ soon-to-be ex-wife and the star of the 1946 noir classic Gilda. Welles plays “Black Irish”, a merchant seaman who gets caught up in a web of delirium, deceit, and murder after falling in love with Hayworth, the wife of a crippled and corrupt prominent attorney. The film was one of the artistic pinnacles of the cycle and included a large number of its conventions. Hayworth’s femme fatale is radiant and deadly as she lounges on the deck of the yacht, smoking and crooning a sultry jazz number. Bizarre and grotesque characters abound, most notably the crippled, skeletal defense attorney portrayed by Everett Sloane (previously appearing in both Kane and Journey) and his hysterically unhinged partner played by Glenn Anders. Both are bathed in a perverse sweat throughout the sea cruise, apparently suffering from alcohol poisoning and dementia. The story is dreamlike, almost unintelligible and filmed in a menacing and distorted way by Charles Lawton, Jr. Welles brings a brooding intensity to his role and joins the ranks of stoic antiheroes exemplified by the likes of Lancaster, Garfield, Ladd and Mitchum. As in Journey into Fear, much of the film takes place at sea, a noir convention Paul Schrader has identified as the “almost Freudian attachment to water”[xi] that recurs in the films. The water motif takes on diverse forms: The bathtub a killer sits in (Laura), or glistening, rain-slick streets (Asphalt Jungle), or a swimming pool the dead protagonist tells his story from (Sunset Boulevard), and surfaces again in Welles’ own Mr. Arkadin and Touch of Evil. The exotic and foreign also figures heavily in the proceedings. The first meeting of the doomed lovers is filled with flirtatious chat of world travelling, in which Welles and Hayworth generate erotic heat. The story moves on a sea voyage from New York City to the Caribbean coast of Mexico to San Francisco, and the topography of the locales is lovingly filmed. The exotic element has taken many shapes in noir, among them Peter Lorre’s perverse ethnic dandy and the statuette itself in The Maltese Falcon, the rare clock that houses a murder weapon in Laura, and the ambiance of Mexico again in Out of the Past. Welles himself had previously examined the attraction/revulsion to the foreign in both Journey into Fear and The Stranger. He also used the flashback voice-over narration of Black Irish to tell the story, a holdover from both Kane and the hard-boiled tradition, and used similarly in Films like Laura, The Killers, Sunset Boulevard, Out of the Past, and Gilda. The murder trial of Black Irish, in which he is represented by his enemy (Sloane), takes on a distinct antiauthoritarian bent, as the pathetically ineffectual judge (Erskine Sanford from Kane) is unable to control his courtroom and the proceedings become a comedic circus. The famous climax in a mirrored “crazyhouse” brilliantly conveys a world of treachery and deceit where nothing and no one is as it seems. The narrator’s fatalistic closing lines are classic noir: “Well, everybody is somebody’s fool. The only way to stay out of trouble is to grow old. So I guess I’ll concentrate on that. Maybe I’ll live so long that I’ll forget her. Maybe I’ll die trying.”

Following his filmed version of Macbeth in 1948, Welles starred in Sir Carol Reed’s masterful adaptation of the Graham Greene novel The Third Man the following year. After demonstrating an affection for tales of international intrigue in three previous films, he was in fine form to portray the ruthless and charismatic Harry Lime, a black market racketeer in post-war Vienna. The film also reunited Welles with his old pal Joseph Cotten, who was cast in the lead. Director Reed had previously made a strong argument that film noir could perhaps cross the Atlantic intact with 1941’s Odd Man Out. Set in a foggy nocturnal Belfast, the earlier film follows an IRA gunman as he is pursued through the night, bleeding to death from a gunshot wound. It is all conveyed in the moody, atmospheric deep-focus style synonymous with noir and should be considered in any study of the movement’s aesthetics. Welles, who had been fascinated with Ireland since his days with the Gate Theatre in Dublin, would surely have found the film riveting. Like Odd Man Out, as both a foreign film (It was an independent production by Reed, who was English and tied to studio system of Britain) and a film set in a foreign locale (Vienna, Austria), The Third Man fails to meet some critics’ definitions of noir. In any case, Welles and Reed continued to push the aesthetic to its logical conclusion. Frank Brady writes of Welles’ considerable influence during the collaboration with Reed: “The first-person singular style of many vintage Wellesian projects…, the baroque construction, distorted camera angles, variegated shadows, and overlapping dialogue does make the film stylistically close to a project Welles might have created…There is also the myth that Welles completely wrote his entire part of Harry Lime…”. To put it another way, many of the noir elements in The Third Man are the same ones evoked by Brady to define the Welles style. The film’s preoccupation with culture clash and multinationalism also seems like a Welles touch, not to mention the famous zither score and the casting of Cotten in the lead.

Cotten plays Holly, a down and out American pulp writer who arrives in Vienna to work for his old friend Harry Lime, only to receive the news of Lime’s death. Holly is questioned by a British intelligence officer, who informs him that Lime was an evil drug trafficker. Furthermore, Lime’s bad penicillin is responsible for the maiming and deaths of countless children in the city. Holly falls in love with Lime’s bereaved girlfriend, drinks a lot, gets beaten up and has adventures with a number of bizarre characters before agreeing to help the authorities bring the still living Lime to justice. The seedy decadence of urban Vienna, a city lined with cabarets and at the mercy of gangsters, drug peddlers, pickpockets, and prostitutes is vividly evoked, as is the city’s architectural beauty. The film took sleaze to an unheard of level in 1949 with its burlesque scene of a dancing girl wearing nothing but pasties on her breasts. Ernst Deutsch gives a hilariously unsettling performance that rivals the weirdest queerly tinged roles of Peter Lorre and Charles Laughton, portraying the flamboyant dandy “Baron” Kurtz. Welles’ performance as Lime is the epitome of ambiguity and duplicity; he is evil and corrupt, yet highly attractive and likable. The climax of the film begins with a dangerous encounter atop a Ferris wheel that includes Lime’s famous nihilistic monologue equating people with ants. It ends in the water, a chase through the city’s labyrinthine sewers that, like the clock tower scene in The Stranger, takes on a tone of sheer horror as the sophisticated Lime is hunted like an animal. The film’s message is highly cynical: The charismatic Lime is killed and Holly doesn’t even get the girl. Still, The Third Man was a huge critical and financial success and Welles received a major resurgence in popularity that even spawned a Harry Lime radio show.

By 1958, Welles had not directed a feature for a Hollywood studio since Macbeth ten tears earlier. Having been let go by RKO and Paramount, Macbeth had been released by the decidedly downscale Republic Pictures. He followed it with Othello in 1952, which found distribution with the arthouse upstarts United Artists. Since his Vienna days with Reed, he had continued to live and work largely in Europe, completely outside the Hollywood system. His final Hollywood film would comprise both noir’s crowning achievement and its death knell.

The cycle seemed to have run its course by 1955, with films like Kiss Me Deadly ratcheting the sex, violence and general malevolence to an unheard of degree. As with The Lady from Shanghai, Welles would set the new standard for the movement. But whereas Lady had been a sophisticated and polished noir gem, glamorous even, Touch of Evil was all the name implied: A tour of Hell; raw, revolting, relentless and brutal. It would epitomize all the depths of depravity and menace that the cycle had aspired to for the better part of two decades, presented with Welles’ usual visual flair. Based on a hard-boiled novel by Whit Masterson, Welles scripted, directed and starred in the Universal film. Charlton Heston was cast as Vargas, the Mexican police official who finds himself battling dark forces in the apocalyptic no-man’s land of a California border town. Welles plays the corrupt and demonic US border cop Hank Quinlan, whom Vargas must outwit as he pursues his kidnapped wife and her gangster captors through a nocturnal world of danger and darkness. Akim Tamiroff gives an oily performance as the Mexican mob boss Grandi. Joe Cotten provides a cameo, as do old friends like Marlene Dietrich (as Quinlan’s old flame, an aging madam) and Mercedes McCambridge (as a predatory lesbian rocker). The isolation and decay of the lawless borderlands is chillingly brought to life by cinematographer Russell Metty, who had previously shot The Stranger for Welles. The fascination with international tensions and ethnicity is foregrounded once again, as are noir’s most popular locales, California and Mexico, which comprise a single sinister entity here.

Welles’ Quinlan is the ultimate noir menace, threateningly tall, hugely obese and humpbacked, with shadowed eyes and large, blubbery lips. His cryptic lines are delivered in stacatto bursts of uncontainable fury. The usual prosthetic nose, fisheye lenses, off-kilter lighting and camera angles further distort his repugnant features, and the mise-en-scene around him is constantly jarred and fragmented by shadows, swinging lights, flashing neon glows and explosive outbursts. It is a self-effacing role for Welles, frightening and, along with Lime, perhaps his best. Quinlan meets his death in the water of a shallow river bottom after being shot by his partner, who reluctantly chooses to ally himself with Vargas. The beautiful Janet Leigh, as Heston’s wife, is consistently bathed in a harsh light, which gives her an overripe, almost cadaverous appearance. The plot moves like a fever dream and includes car bombings, murders, rape, torture, prostitutes, strippers, drug use, corrupt authorities, the Mexican mafia, a perverted simpleton, lesbian bikers, and leather-clad beatnik junkies. Welles exceeded himself in constructing the film’s sound design, a virtual landscape of Mexican radio, screeching tires, sirens, explosions, bordello jazz and rock&roll. For all its achievements, the film was produced and marketed as a sleazy B-picture and failed to make much of an impression on critics or audiences of the time.

After Touch of Evil, the noir cycle had more or less played itself out. Welles had taken the aesthetic style to its peak, and the imagery and themes of the movement had gone as far as the Production Code of the era would allow. Additionally, audiences were seeming to tire of such dark, pessimistic fare. The “last” film noir was also the last film Welles would direct for a Hollywood studio. Since his Vienna days, he had continued to live and work almost exclusively in Europe, where his films were always well received. It was there that he continued to refine the visual style and themes of noir, but with an avant-garde sensibility associated with the burgeoning “foreign film industry”. In the years following Touch of Evil, he wrote, directed, and acted in both the surreal “Euro-noir” Mr. Arkadin, and an adaptation of Franz Kafka’s The Trial. Both films showed that he had not abandoned the themes and formalism of the movement he had helped pioneer.

A multinational European production, Mr. Arkadin was filmed in 1958, but not released until 1962. Welles based the script on one of his own Harry Lime radio plays. In typical over-the-top fashion, the story begins on a shadowy waterfront where a peg-legged villain is pursued after murdering a man. Robert Arden portrays Van Stratten, a seedy American hustler adrift in Europe, who witnesses the murder. He soon finds himself involved in shady dealings with the demonic tycoon Arkadin (Welles) who hires him to investigate Arkadin’s own past. The action moves all throughout Europe and Latin America as Van Stratten seduces Arkadin’s daughter (Welles’ wife Paula Mori) either out of love or greed, and finally discovers Arkadin’s past as a racketeer, gigolo, wartime informant, and slave trader. The tycoon commits suicide by crashing his plane as Van Stratten reveals all to the daughter.

Mr.Arkadin might well be considered Welles’ low-budget arthouse retelling of Kane with all the trappings of a film noir, as Frank Brady compares the two films:

Welles made Gregory Arkadin into a virtual caricature of Charles Foster Kane, a fabulously wealthy tycoon with a castle in Spain rather than a Xanadu in Florida (Years later, Welles likened Arkadin to Harry Lime, rather than Kane: “because he is a profiteer, an oppurtunist, a man who lives on the decay of the world”)…(Mr.Arkadin) became the latest of Welles’ intensely personal films, related thematically to Citizen Kane and The Lady from Shanghai. The echoes of Kane were picked up by almost every critic: the uncommonly wealthy, powerful man, whose life story is revealed in bits and pieces ferreted out by a resourceful stranger…In Kane, Welles seemed to be saying that a man is far more complex than the sum of his parts, in Arkadin Welles has become more disillusioned. Here, truth becomes the instrument of destruction, first for all who know Arkadin’s sordid background, and finally for Arkadin himself, leaving behind the daughter who had long lost the innocence Arkadin hoped to protect, and the jackal-like Van Stratten, whose self-serving interests make him even less sympathetic than the evil Arkadin. Here, too, is a wealthy, powerful person whose relationship with a younger man is filled with duplicity. Van Stratten is victimized, just as is the young sailor Welles plays in Lady from Shanghai. Welles continued his concern with revealing the degrees of power held by the very rich and with exposing the machinations they engage in to retain that wealth and power.[xii]

Welles undoubtedly returned to familiar conventions in the film. Van Stratten, the low-rent American drifter conning his way around the Continent, bears a striking resemblance Cotten’s two-bit pulp writer Holly in The Third Man, even providing similar street-smart voice-over narration. Welles’ Arkadin is a virtual parody of deceit and duplicity, a bizarre and sinister menace with heavy stage make-up, fake nose, horned hair, and a Mephistophelean beard. A theme of the past haunting the present is foregrounded, as in Kane, The Stranger, The Third Man, and countless noir classics. Akim Tamiroff, looking like a character from “a tortured expressionist drawing by George Grosz”[xiii] and many other offbeat actors are featured, as is Patricia Medina, Joseph Cotten’s wife, as Van Stratten’s sleazy rejected girlfriend. Other characters include a queerly perverse pawnbroker, a crazy flea circus ringmaster, an aging heroin junkie, and an ex-prostitute and slave-trader who is now the wife of a Mexican politician. The film boasts two unusual femme fatales: Arkadin’s daughter, a “good girl” who nonetheless puts Van Stratten’s life at risk at the hands of her diabolical father; and Van Stratten’s jilted girlfriend, like him a bed-hopping oppurtunist, who parties with Arkadin and threatens to expose Van Stratten’s seduction of the daughter. The international cast brilliantly captures both the fascination with, and the fear of, the foreign, and despite the dizzying array of locales, most of the action is centered around the oceanfront or at sea. Again, the conventions of the cycle are pushed to their limits. The film takes the weirdness of noir imagery to an hallucinatory level that aggressively disorients the viewer. The cinematography of Jean Bougoin successfully bonds the cycle’s baroque look with the surreal absurdism that was in fashion among continental directors like Fellini and Bunuel. Virtually every shot in the film is from a low angle. The cityscapes take on a more extreme expressionistic form, as though the whole world is shadowed and skewed. One particularly stylized sequence is a nightmarish masquerade party at the castle, and another on a boat features Arkadin’s leering Satanic form bobbing toward and away from the camera with the sway of the sea as the background zooms in and out behind him. Eric Rohmer, who reviewed the film for Les Cahiers du Cinema, evoked its noir spirit: “…an absolutely brilliant illustration of a genre which has become more and more debased…This unrealistic tale rings even more true than many tales where great care has been taken to ensure verisimilitude…The actors…play on their own physical, and even ethnic qualities. The power of money is depicted with a precision that only Balzac would have envied. All these real elements make up an exceptional world…”[xiv]

Mr. Arkadin was followed by The Trial in 1963, another independent international production that found Welles still working in highly stylized, high-contrast black and white. Like his beloved “Heart of Darkness”, Kafka’s book was another modern classic which had much in common with the imagery and themes of noir. Brady describes the film as “all at once a prophetic vision of the totalitarian state, a labyrinthine nightmare, a parable of the law, a study of paranoia, and a paradigm of the inability of man to communicate”.[xv] As in Kane, Magnificent Ambersons, and Mr.Arkadin, the film opens with a theatrical voice-over introduction by the auteur himself. Ever one to top himself and his own conventions, The Trial’s introduction is a lengthy parable concerning “The Law”, accompanied by drawings that vaguely recall Iron Curtain propaganda. Welles concludes by stating that the story that will follow has the logic of a nightmare.

Kafka’s fictional alter ego Joseph K. is awakened one morning by shadowy government agents who emerge from his closet and inform him he is under arrest for an unspecified crime. He is never informed of the nature of the offense, nor whether he is guilty or innocent, and is allowed to carry on his everyday life until his trial date. He moves from one paranoid encounter to another in an oppressive and ghostly nocturnal cityscape, menacingly captured by cinematographer Edmond Richard. As with his previous film, Welles pushes the cycle’s conventions and themes to their logical, if surreal and absurd, potential. Anthony Perkins is hilarious and haunting as Joseph K., Welles’ final noir protagonist, and yet another not-quite-innocent man who finds himself haplessly embroiled in a web of intrigue. All Welles’ thrillers had embraced this archetype to some extent: Cotten’s hunted munitions expert in Journey into Fear, and his sleazy, oppurtunistic bookwriter in The Third Man; Welles’ Nazi on the run whose sense of nationalism brings about his demise in The Stranger, and his sailor in The Lady from Shanghai whose infatuation with a married woman leads to tragedy; Heston’s Mexican cop whose rigid honesty and ethnicity mark him as Quinlan’s target in Touch of Evil; and Arden’s greedy gigolo adventurer whose lust for a sinister tycoon’s daughter leads to mystery and murder in Mr.Arkadin. All find themselves out of their element and in danger, their lives becoming a disorienting, paranoid nightmare.

In addition to Welles’ sardonic Advocate, who emits steam from his head, strange characters include a moustached woman, a drunken stripper and a mysterious man with a whip. Beautiful, aggressive women seek to seduce and betray Joseph at every turn. The cast includes Tamiroff, Paola Mori, and Katina Paxinou from Mr.Arkadin., and the film makes comical references to Journey into Fear and Touch of Evil. The constantly shifting locales Welles deployed throughout Europe further distort the fragmented narrative and help create the feeling of a claustrophobic city folding in on itself. The soundtrack mixes jazz with classical music, adding to the dreamlike quality of the production. In the film’s ghastliest scene, Joseph is trapped in a closet with two men who seemingly beat each other to death, their pained and distorted features chillingly illumined by a swinging light. The climax is, of course, a trial scene and is presented as a laughable circus, a humorous indictment of the inefficacy of corrupt authority. It recalls the courtroom scene in Lady from Shanghai, but unlike Black Irish, there seems to be no escape for Joseph K. The darkest vision yet of urban alienation, powerlessness and identity loss, Welles described the film as “a contemporary nightmare, a film about police bureaucracy, the totalitarian power of the Apparatus, and the oppression of the individual in modern society”.[xvi]

Following The Trial, even Welles abandoned the styles and themes of film noir, continuing to work mostly in Europe on more classically oriented features like his earlier Shakespeare adaptations. He remains best known for Citizen Kane and a legacy of half-finished films. What should not be forgotten is his rich contribution to the single most important movement in American film aesthetics; its themes, archetypes, iconography, motifs, visual style, sounds and narratives. The art of darkness that is film noir.

[0] Another pristine monochrome noir visitation currently on Netflix is David Fincher’s Mank, starring the indispensable Gary Oldman as the beleaguered screenwriter of Welles’ Citizen Kane along with an incredible Tom Burke as the great Orson himself. They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead, the 2018 Netflix documentary on Welles’ production of The Other Side of the Wind is also required viewing.

[i] Schrader, Paul. “Notes on Film Noir”. Silver, Alain and Ursini, James (ed.), Film Noir Reader (1996 Limelight Editions, NY), p. 53.

[ii] Place, Janey and Peterson, Lowell. “Some Visual Motifs of Film Noir”. Alain and Ursini, p. 66.

[iii] Callow, Simon. Orson Welles: The Road to Xanadu (1996, Viking Penguin, NY), p.501.

[iv] Callow, p.502.

[v] Brady, Frank. Citizen Welles (1989, Anchor Books, NY), p.328.

[vi] Brady, p.329.

[vii] Brady, pp.330-331.

[viii] Brady, pp.331-332.

[ix] Brady, p.332.

[x] Brady, p.379.

[xi] Schrader, p.57.

[xii] Brady, p.467-468.

[xiii] Brady, p.467-468.

[xiv] Brady, p.469.

[xv] Brady, p.528.

[xvi] Brady, p.531.

Friends We’ll Miss: Gary Floyd (1952-2024); Paul Auster (1947-2024)

Among the great ironies of the early 1980s American hardcore punk scene was that two of the movement’s only blatantly queer and cross-dressing front-men were in bands hailing from Austin, Texas of all places: Randy ‘Biscuit” Turner of the Big Boys (1949-2005) and Gary Floyd of The Dicks. Even more remarkable, both bands achieved a level of notoriety and acceptance within the top ranks of the early (overwhelmingly macho and heteronormative) US hardcore scene that no other Lone Star State acts of the era could boast of. Gary was a true art terrorist, very much a close cousin of John Waters’ muse Divine while also bearing something of a resemblance to none other than Orson Welles when not in drag. He was alternately terrifying and charismatic, while his vocal style was more that of an old Texas blues howler rather than a California screamo skate punk (Witness his later San Francisco-based outfit Sister Double Happiness for further evidence of this). In recent years I had the pleasure of seeing Gary perform at reunion shows with The Dicks and also spent a bit of time with him at his art show openings and book signing events. While Jello Biafra once described Gary as “a 300-pound communist drag queen who can sing like Janis Joplin,” offstage Floyd was as sweet and gentle as a lamb. He was a rare talent, a subcultural pioneer on multiple levels, an ace provocateur, and at least in his later years, a kind and compassionate human being possessed of a quiet and deep spirituality. He will be greatly missed.

Speaking of things noir and detective novels, I’m ashamed to admit that I just never got around to reading The New York Trilogy, considered by many to be among the central texts of American postmodern fiction. This is particularly embarrassing as I am a longtime devoted reader of New York literature in general and postmodern authors in particular, but I guess I was too busy digesting weighty avant-garde tomes by DeLillo, Pynchon and Vollmann during the 1980s and 90s to give the recently deceased Paul Auster his due, although I was always aware of his books. As a result, I mostly came to know Auster’s work through the extraordinary and heartfelt oddball films of three interrelated screenplays he wrote during the Miramax independent film boom of the 1990s: Smoke and Blue in the Face (both 1995), followed by Lulu on the Bridge (1998), which comprise a cinematic New York trilogy of sorts. The first two films, directed by Wayne Wang, are certainly companion pieces, set among the habitués of the same Brooklyn cigar store; while Lulu, directed by Auster himself, moves in a fever dream from the jazz club milieux of New York City to Dublin, Ireland (Auster had previously written the script for 1993’s The Music of Chance and a fifth Auster film both scripted and directed by the author, The Inner Life of Martin Frost, was released in 2007). Among many other delights of Auster’s cinema, the end credit sequence of Smoke, set to Tom Waits’ haunting classic “Innocent When You Dream”, is an achingly beautiful short form masterpiece in its own right (see below).

In addition to the ubiquitous postmodern and surrealist tags so often attached to his literary style, Auster was also considered a quintessential New York writer and this is readily apparent in the three films. The ever powerful Harvey Keitel, Scorsese and Ferrara’s muse of the New York mean streets, plays the lead in all three, while NYC’s dirty boulevard punk poet Lou Reed makes rare film appearances in both Blue in the Face and Lulu on the Bridge (as a version of himself no less and with several short intercut monologues throughout Blue, which also features his music). Multi-hyphenate NYC Lounge Lizard John Lurie provides the musical score for both these films as well and also appears onscreen in Blue. Other icons of New York cool that appear in the Auster films include Victor Argo, David Byrne, Stockard Channing, Kevin Corrigan, Willem Defoe, Richard Edson, Giancarlo Esposito, Michael Imperioli, Jim Jarmusch, Madonna, Luc Sante, Mira Sorvino, and Forest Whittaker. One gets the impression watching these wonderful little films that everyone involved is on hand because they love Auster’s vision of their own New York City; the films are something like home movies, an improvisational gathering of like-minded local friends with the camera left running (a sensibility Auster’s films share with those of his dear friend and collaborator Jim Jarmusch). It’s well past time for me to begin catching up with Auster’s novels so I’m off to begin the slim volume Man in the Dark from 2008, which has been gathering dust on my shelves for many years. See you in the great epic experimental novel in the sky, Mr. Auster. Or perhaps at the glorious eternal 24-hour movie house or cigar store in the sky.

![Film Noir Friday: The Stranger [1946] - Deranged LA Crimes ®Deranged LA Crimes ® Film Noir Friday: The Stranger [1946] - Deranged LA Crimes ®Deranged LA Crimes ®](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!K4K2!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F099269fe-4f0a-42d3-9b90-b797c2ff6b6e_575x779.jpeg)

INTERESTING READ